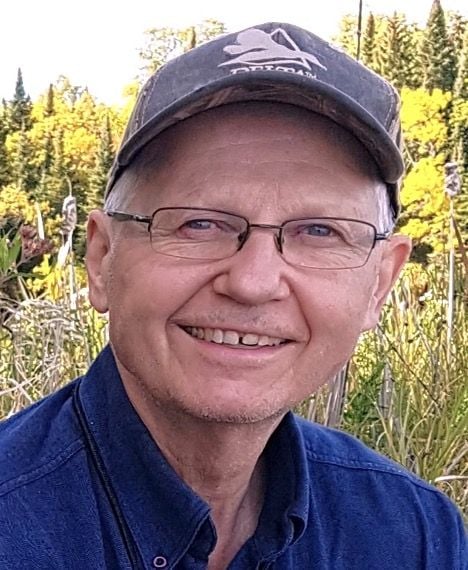

For over two decades, my deer hunting trips began with an early morning boat ride. Once ashore, boat stored and guided by a headlamp, I would shoulder my gear and begin the walk through the brooding forest of the Canadian Shield to my blind.

I settled in as dawn seeped through the gloom, listening as much as I watched. About 15 minutes before sunrise, the silence would be broken by chattering Canada jays coming off their nighttime roost. It wouldn’t take long for them to find me, or the lump of venison back fat I had hung nearby. For me, the hunt didn’t really start until my feathered pals showed up.

Hunting deer in the wild woods

Read Also

Canadian Cattle Association names Brocklebank CEO

Andrea Brocklebank will take over as chief executive officer of the Canadian Cattle Association effective March 1.

As one travels north from Manitoba’s grasslands ecoregion, open vistas give way to the aspen parkland, a mix of open country and aspen bluffs. Keep going north and you hit a forest-dominated ecological zone called the boreal transition. That includes the Riding Mountain and Duck Mountain areas, the central and northern western region and Interlake, and the southern part of eastern Manitoba, including the Whiteshell Provincial Park.

It was once a hotspot for moose, although these days the noble beasts are struggling to hang on. White-tailed deer first showed up about a century ago, and have now become the dominant ungulate.

These forests are mostly Crown land, so accessing hunting opportunities comes down to one’s willingness to hunt in wild country. Many Manitoba deer hunters, myself included, have taken up that challenge.

My first years of deer hunting took place in farm country in western Manitoba. My brother and I sat on field edges at dawn and dusk, but we walked through wooded pastures and fields dotted with aspen bluffs the rest of the time. Farm country deer usually settle into heavy cover through the day.

As my son got to deer-hunting age, this approach — involving quick decisions and shots at running animals — didn’t seem like a good way to introduce a beginner.

Experienced hunters told me that deer in forested regions tend to be more active during the day. Hunting from a stand for longer periods could be effective. The deer could be moving at any time.

With a family cottage in the Whiteshell, I decided to give its mixed woods, swamps and granite outcrops a try. Deer numbers were high in the early 2000s, but an experienced Whiteshell hunter cautioned that “the deer are everywhere and nowhere.”

Because every bit of forest is potential habitat, the deer tend to be thinly distributed. That said, landscape features like lakes, swamps, beaver floods, clear-cuts and rock outcrops funnel their movements. To effectively hunt from stands, I needed to find choke points.

After poring over air photos, we took some hikes in the early autumn. In my area, the good-looking spots near roads and trails usually had tree stands or ground blinds. That was more hunting pressure than I was expecting, so I looked further afield.

We launched the boat and scouted the roadless area across the lake. The best spot was a tiny flowage interrupted by beaver ponds. The open creek bottom gave way to robust stands of spruce, fir, black ash and aspen. For some reason, the mix of vegetation and landscape features concentrated deer like crazy — at least by by Whiteshell standards — and there was no evidence that we would be sharing it with other hunters.

We built ground blinds along a one-kilometre stretch, providing options for various wind directions and changes in deer movements. At least some of that stretch would be flooded by beavers each year, which made the unflooded crossing points all the better. We didn’t have game cameras when we started out. Hunting decisions came down to watching for trails with the greatest intensity of fresh tracks.

The approach to bagging a deer was deceptively simple: park one’s butt on a stool for as long as it took to intercept a passing animal. What I had been told about forest deer movements proved true. My records show a peak of encounters around 9 a.m., but lots of deer, including most of the mature bucks, were taken between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. This included the muzzleloader season, well before the peak of the rut.

It’s a type of hunting that involves a lot of patience and nature watching.

Despite the comparative peak in deer populations in that first decade, we still had to be on stand for an average of 1.5 days to encounter one good-sized deer. That’s lots of time ponder life and whatever else happens to come along to pass the time. Even the most avid outdoor enthusiasts find it challenging to watch the same patch of landscape for a whole day.

Enter the whiskey jacks

Some years ago, I was happy to see that Canadian Geographic magazine named the Canada jay as our national bird. Its range is mostly within Canada and is found in coniferous forests from our southern border to the tree line.

Outdoors people often called them “camp robbers,” a nod to their boldness and habit of filching morsels from campsites. Unlike almost any other wild critter, Canada jays that encounter people usually move in for a closer look, especially if you’re associated with food.

My favourite unofficial name for them though, is whiskey jack. The term is derived from an important figure in Algonquin mythology. Wisakedjak, a figure that shows up in many stories, is a trickster and transformer. I don’t know about the transformer part, but the trickster tag makes sense for a bird known for snatching food under the noses of people and other large predators.

Whiskey jacks are in the same family as other jays, magpies, crows and ravens. They are relatively fast learners and have long memories. The latter trait pairs nicely with their unique habitat of caching food in the summer and autumn for use in winter and early spring. Their tie to coniferous forests can be explained, at least in part, by their use of the scaly, acidic bark of conifers to store insects and other delectables for the winter.

Caching behaviour also helps them cement their place as one of the earliest-nesting songbird in these parts. Eggs are usually laid by mid-March.

Hunting buffet

I soon learned that a rifle shot could be a siren call for whiskey jacks. They gather quickly and wait impatiently for the hunter’s knife to do its work. When the steaming mass of offal is released, they’re ready to jump on the bounty, both for their immediate hunger and for their winter stores.

We watched this scene unfold when my son took our first Whiteshell deer. After his buck was field dressed amidst the chatter of scolding whiskey jacks, we cut out some suet and hung it from our blind. We soon had birds sitting on the blind rails and our gun barrels, and even filching meat from sandwiches that we held up.

It didn’t take me long to decide that feeding whiskey jacks livened up a day in the deer blind — Hence my tradition of hanging a lump of back fat big enough to last a day of their foraging.

Their day is an endless repetition of pecking away and flying off with full beaks to cache. The little kid in me breaks that up periodically by offering tasty stuff from my hand. They go nuts over bagels, thinking nothing of sitting on my arm and yanking out the biggest pieces possible.

Watching their antics is a great joy, and feeding and caching the entrails might add a week’s worth of winter survival rations for the troop. Picking at my back fat offerings would extend that a little further. Lest I get too maudlin, I remind myself that these are survival tactics for these year-round, boreal residents.

Almost without fail, I’m entertained by a group of three birds.

Whiskey jack adults will accept one of their young to overwinter with them, while the rest are chased off. Being the chosen one comes with responsibilities to help feed their siblings during the next nesting season. This social arrangement also sets up an intergenerational element that, when combined with good memories, may help to explain why, over two decades, a troop of whiskey jacks would find me without fail on my first day out every year.

Whiskey jack tales

Whiskey jacks have a wide array of whistles, mews and chirps that carry on constantly through their foraging. This changes to harsh chatters when a predator’s near. A couple of times I heard it, it announced a goshawk, but it once signalled a furtive pine martin that circled my blind for about 20 minutes before it warily moved in on the deer fat. The scolding whiskey jacks were forced to watch from a distance.

My whiskey jack distraction makes me a less effective deer hunter, no doubt. The odd animal must slip by when I’m busy with the birds. That said, I value this window into the natural world almost as much as the privilege of taking a deer. People always ask why I don’t focus on easier hunting spots all these years. Part of my answer would be, well, they don’t have whiskey jacks.

One of my most memorable encounters occurred after I had taken a nice buck from a stand we call Buck Point. When I walk up to an animal I’ve taken, I pause a bit to reflect on the experience, thanking Mother Nature, for a lack of a better way to put it, before the dressing knife comes out. The assembled birds vocalized their impatience though. When I completed the field dressing, it was whiskey jack mayhem.

Eventually the carcass was loaded onto my calf sled — a great assist for hauling a deer out — and the kilometre trudge back to the boat began. One of the troop must have decided that the fatty edges of the carcass beat the gut pile, because it followed me the whole trip out, picking out and caching fatty bits every time I stopped to catch my breath.

The bird finally gave up when the animal was loaded into the boat. I last saw it flying up the creek, presumably, back to the gut pile. As it disappeared, a sentimental, hopeful thought came to mind:

“Same time, next year, fella?”