Better feed quality is always a plus, but when it comes to silage inoculants, it’s one more input weighing into the producer’s cost of production. Anyone hoping it will salvage poor silage may be in for a rude surprise.

“It’s not for everyone,” said Karis Hutlet, a sales associate and agronomist with Marc Hutlet Seeds in Dufresne, Man. “We have a healthy number of customers that use it, and we have a big part of our customer base that doesn’t.”

But Hutlet makes one point clear when discussing the potential benefits of silage inoculation.

Read Also

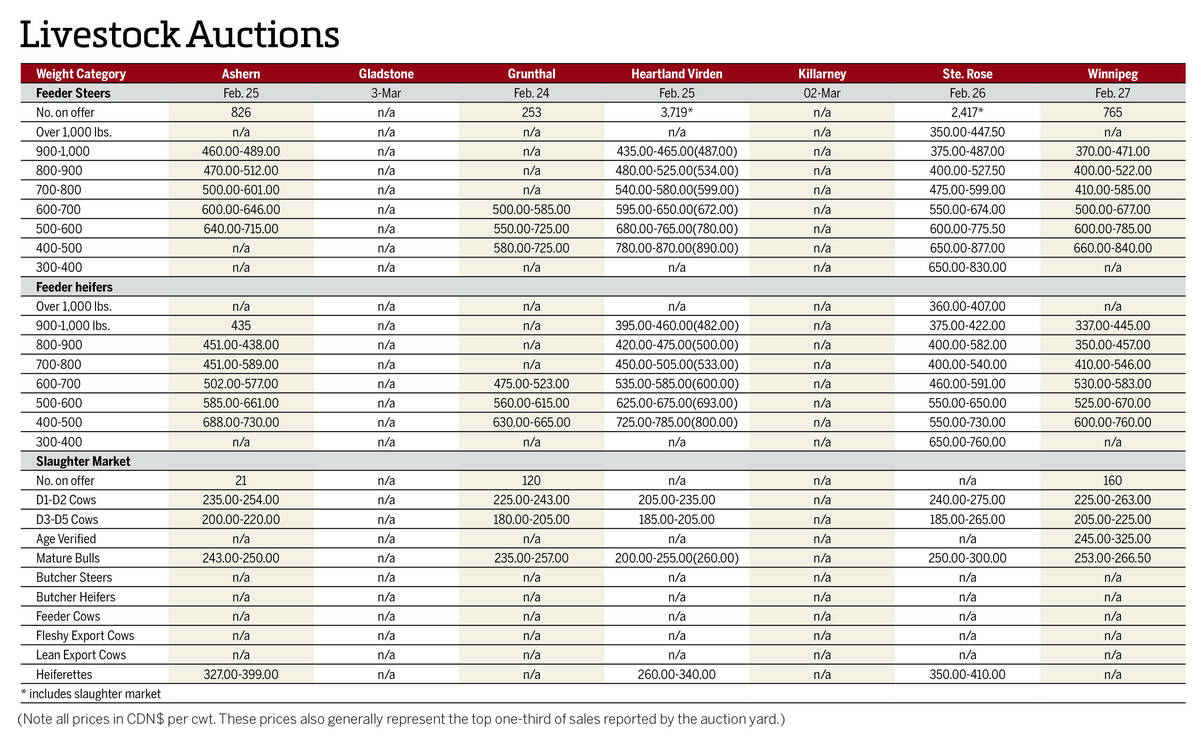

Manitoba cattle prices, March 4

Chart of weekly Manitoba cattle prices.

“It’s not going to make bad silage good, but it’s going to make good silage better,” she said.

Corn silage season is rapidly approaching in Manitoba and some producers may consider applying inoculant.

Cindy Jack, livestock and forage extension specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, agrees. Quality should be backed by the basics.

“Good management is the most effective way to reduce dry matter and energy losses in ensiled forages,” she said. “Ensuring the silage is at the proper moisture, having the proper chop length, eliminating oxygen by packing bunkers and bales well, covering the bunkers and using enough plastic on bales will all help reduce spoilage.”

Inoculant family tree

Silage inoculants have progressed through three distinct generations. First-generation inoculants primarily consisted of natural lactic acid (homolactic) bacteria. The resulting fermentation was heavy in production of lactic acid compared to later generations, which also put out substances like ethanol, acetic acid and carbon dioxide.

Forage extension resources at the University of Wisconsin-Madison tagged those homo-fermative products for better dry matter preservation (since dry matter isn’t lost through carbon dioxide conversion) and better chance of improvement to animal performance, but their use in corn silage was limited. The university instead slated them for use in hay silage.

For ensiling corn and cereals, the first generation of inoculants encountered challenges with feed shelf life. They had limited ability to stabilize silage from those crops so results were inconsistent and frequently led to unwanted heating and spoilage.

The lactic acid may keep unwanted moulds and spoilage bacteria from forming by quickly lowering pH, a 2014 report from the University of Alberta noted, but after the bunker is re-exposed to air, yeast can use that acid to grow.

“At this point, both yeast and moulds can rapidly utilize the sugars for growth, reducing the nutrient density of the silage,” authors noted. “Bunk life of the silage declines with this loss in nutrient density frequently occurring before cows consume the silage.”

Hutlet said the first generation of inoculants is now obsolete.

“We don’t have anyone using it. It’s just older strains that aren’t as crop-specific.”

The successors looked to a bacteria called Lactobacillus buchneri. The resulting heterolactic fermentation, which added acetic acid, improved the aerobic stability of silage.

“The most popular one, by far, is the second generation that included the L-buchneri bacteria,” Hutlet noted.

More recently, a third generation was introduced. It often contains multiple strains of bacteria and enzymes. These advanced formulations are designed to further optimize fermentation, reduce dry matter losses and enhance nutrient preservation, ultimately offering farmers greater control over the ensiling process.

“The third generation uses a different strain of L-buchneri that has been shown to uncouple cell walls, reduce the lignin in your feed and improve fibre digestibility,” said Hutlet.

She sees a big upside to these third-generation inoculants, but they don’t represent a big portion of her business.

“It’s a bit of a specialty product. It also comes with a price,” she said.

Are they worth it?

There are few published studies that examine the return on investment of silage inoculants, and those that have been done are mainly focused on dairy operations.

That leaves beef farmers, who have increasingly gravitated toward silage in Manitoba, with little data.

The economic benefits of better feed quality in general are well established, and the few dairy-oriented studies did show a positive return on investment over time.

The question is whether the inoculant will pay for itself in terms of animal performance, feed efficiency, reduced need for additional feed supplements or feed quality consistency.

Jack says timing is one reason dairy farms have been more receptive to silage inoculants.

“Beef producers generally feed silage in the cooler months, whereas dairy producers typically feed year-round, and the warm weather can cause the silage to spoil faster, so inoculants can be useful in preventing spoilage on the face of the pile,” she said.

Hutlet said it depends on the farm.

“We have some extremely high-producing dairy farms where they’re breaking things down to parts per million. They’re looking at very precise science.”

If a 200-millilitre increase in milk production per cow can be achieved, as some data shows, it adds substantially to the balance sheet.

On the other hand, some beef customers are less concerned with precision or economies of scale.

“Different types of farms have different priorities but we find that the farms that have used it are still using it, and people that try it continue to use it,” said Hutlet.

She said the inoculant application process is another reason new customers may shy away.

“It’s not like you just magically sprinkle this on. It comes with a machine that you have to service. You have to mix your inoculant with water and make sure that your machine is calibrated and that your nozzle isn’t clogged. You have to calculate how many tonnes are coming in per acre per hour, and then set that on your monitor.”

For bigger dairies that have enough hands and are used to doing it, that’s not an issue, “but for the smaller guy that’s trying to run a chopper and hurry up, it’s just kind of a lot sometimes,” Hutlet said.

As well, inoculants don’t consistently improve silage quality.

“Objectively speaking, you’ll see good results maybe four years out of five,” Hutlet said. “Maybe one year in those five, you could have a pile with inoculant and a pile without, and you may not see a difference.”

That inconsistency is not because the inoculant isn’t working, she said. It’s more likely because the silage had high quality in the first place.

“It’s because your corn silage was that good, at the proper timing, covered properly, etc. There’s not always consistency in the results or the final product, but that’s kind of a good problem to have. It can act a bit as insurance.”