Canadian agriculture is sequestering more carbon than originally thought, but it’s also burning more diesel fuel, according to a new report from the National Farmers Union.

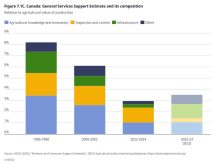

In August, the NFU released the third edition of its Agriculture Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Canada report. It reflected updated information from the latest national inventory that the federal government released this year.

Why it matters: Farm greenhouse gas emissions are a hotly debated topic in agriculture.

The 2023 inventory report contained several methodology changes, the NFU said. In particular, it drew attention to new values for “crop residue C input.” Those new values stemmed from recalculations due to new data from the 2021 Census of Agriculture.

Read Also

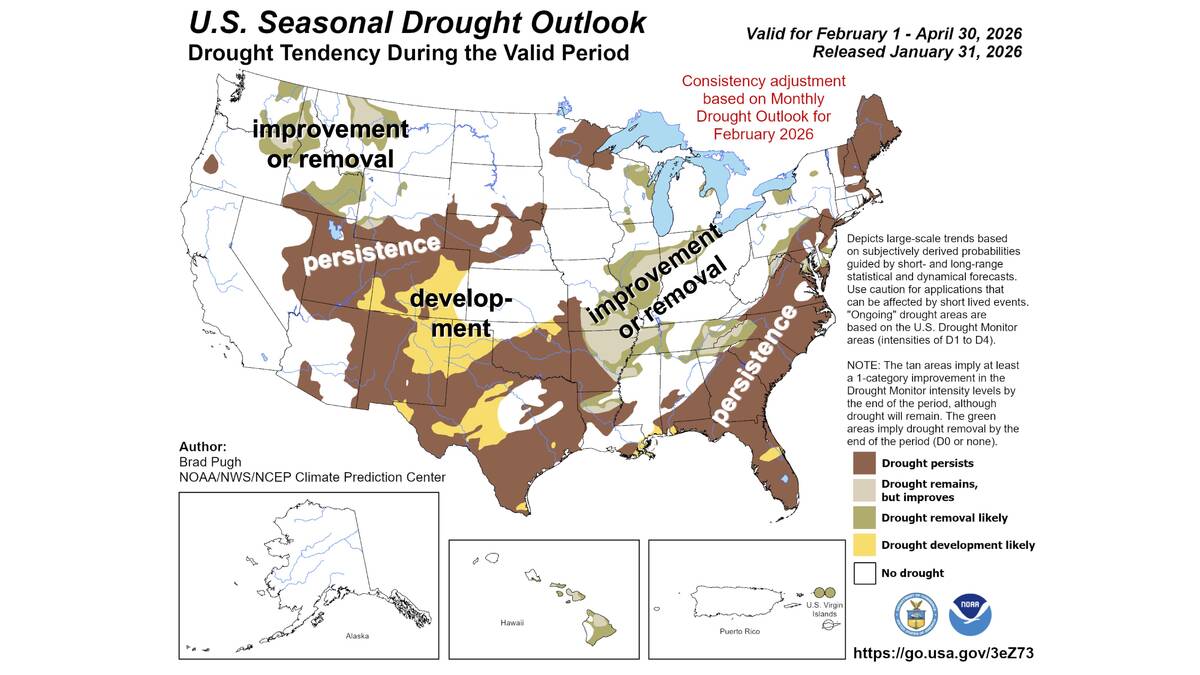

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

All told, “trendline average soil carbon sequestration in 2020 and 2021, from all sources and causes, is up about 10 percent,” the NFU said.

Soil carbon sequestration is estimated at 22 million tonnes per year of carbon dioxide equivalent, up from 20 million tonnes suggested in the 2022 inventory report.

Environment and Climate Change Canada also changed the way it models on-farm fuel use and associated emissions.

The exact nature of that change isn’t clear, said Darrin Qualman, author of the report and the NFU’s director of climate crisis policy and action. Attempts to clarify with ECCC weren’t fruitful, he added.

As best he could tell, prior to the 2023 national inventory report, the ECCC said tillage reduction was leading to generally consistent fuel use year to year. A graph in the NFU report shows emissions from on-farm diesel fuel use fluctuating between eight and ten million tonnes per year from the early 2000s to present.

Based on lengthy quotes from the inventory report in the NFU report, ECCC appears to have decided this assumption was incorrect, and rebalanced the way it splits use of fuel between on-road and off-road vehicles, including use of farm equipment in the field.

As a result, emissions from on-farm diesel use climbed steadily from 1990 until the late 2010s instead of being relatively flat, according to the EEEC. Emissions begin to drop again between 2018 and 2021, but still remain slightly above the projected emissions from the previous national inventory.

Qualman said the macro trends remain the same, regardless of the minutiae.

“We’re not uncertain about the trend line,” he said. “As we’ve dramatically increased fertilizer tonnage, we’re not uncertain as to whether the emissions have gone up or down. We’re certain that the emissions have gone up.”

There is uncertainty, but Qualman said that uncertainty is not the same as saying they don’t know if emissions are significant.

“We just have a little question about where they are in absolute terms,” he said.