If everyday Canadians are struggling to stay afloat in a time of 20 per cent inflation, imagine being a producer having to deal with more than double that amount.

That was the number that Darren Bond, farm management specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, drove home regarding the inflation level farmers have had to manage for their operating costs from 2020-25.

“It’s something that when … you can actually see those numbers … it is a little bit sobering because I think a lot of producers have felt that inflation,” said Bond.

Read Also

Trade uncertainty, tariffs weigh on Canadian beef sector as market access shifts

Manitoba’s beef cattle producers heard more about the growing uncertainty they face as U.S. tariffs, and shifting trade opportunities, reshape their market.

WHY IT MATTERS: Market uncertainty and international instability is squeezing the farm sector with inflation as high as 50 per cent since 2020.

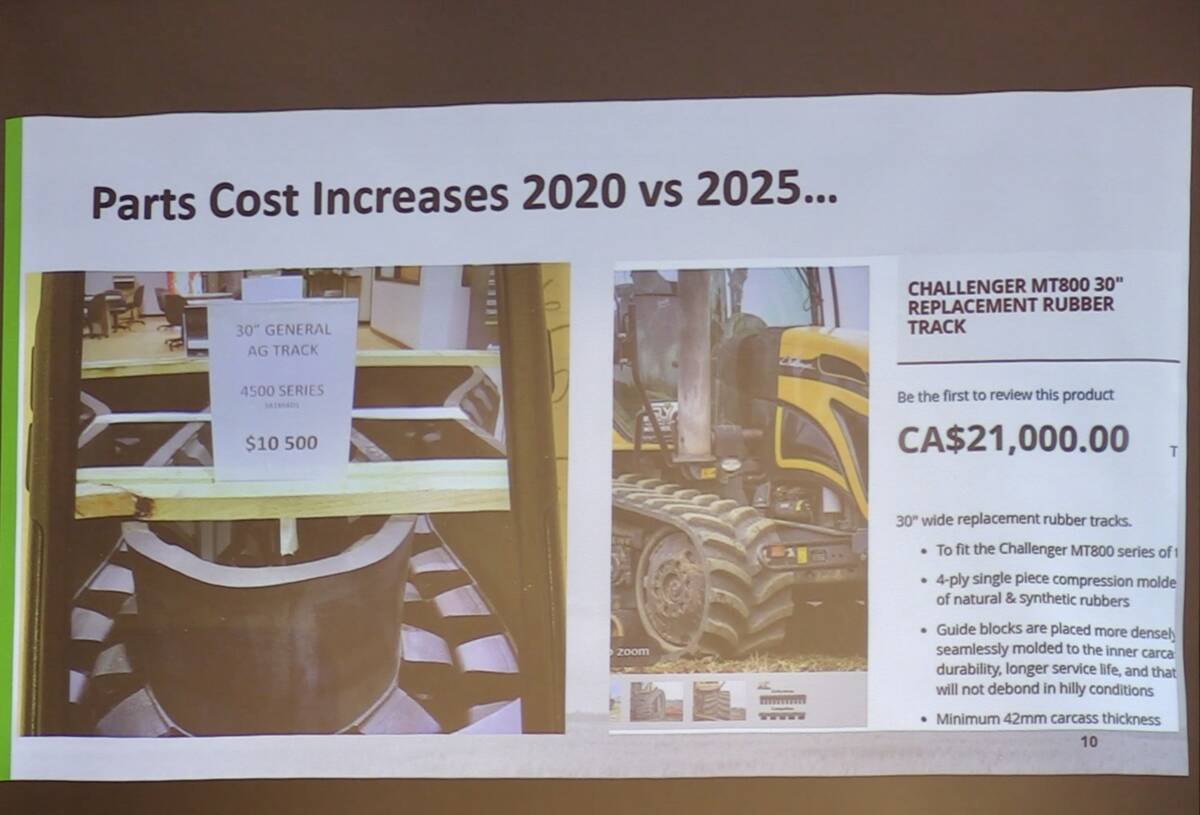

Bond used an example from his own farm to show how severe a price jump for replacement parts cost can be.

In 2020, Bond priced out replacement tracks for his two-track Challenger tractor. At that time, each track cost $10,500.

Five years later, in 2025, the price for those same tracks had doubled to $21,000 per track.

Eye-bulging price jumps such as this aren’t limited to replacement parts.

Manitoba Agriculture publishes a Cost of Production Guide for farm machinery every two years.

Bond said that if you were to look at the past three guides — approximately covering the past six years — the average cost of equipment has gone up by about 50 per cent.

“When we look at the rental cost, which roughly approximates the cost to operate that equipment for a producer … it’s much the same, again, 40 to 50 per cent,” said Bond.

The high degree of inflation in the farm sector isn’t limited to agricultural equipment.

Bond said that the latest farmland value report by Farm Credit Canada showed roughly a 50 per cent increase in appreciation for Manitoba farmland between 2020 and 2025.

Farmers are also feeling the cost squeeze of what it takes to put a crop in the ground.

“When we look at our cost of production document that the province does every year … we look over that five-year time span from 2020 to 2025, depending on the crop … we’re in that 40 to 50 per cent inflation amount,” said Bond.

In a tight profit margin environment, Bond said that he does see promise for some commodities in 2026, but it will require some work.

While Bond says crops such as wheat will be hard to generate a profit from, but soybeans may offer more of a profit potential.

“A large part of that is it doesn’t use near the amount of fertilizer that canola and wheat does,” said Bond.

Producers will also need to keep a close eye on pricing opportunities.

Those who are prepared and know their cost of production will be better positioned to react when better pricing comes along and before markets go back down.

A familiar approach to fertilizer efficiency can also provide some cost of production guidance for producers, said Bond.

“We hear the 4Rs of fertilizer all the time, and that’s often through an environmental lens … but we could also use it through a profitability lens as well,” said Bond.

For example, he said that producers who have the ability to choose between urea and anhydrous as a nitrogen source may save themselves about 15 per cent.

Producers who know where and when to apply their fertilizer are also more likely to come out on top.

“Take nitrogen, for example,” said Bond.

“Are you in a low soil reserve, high soil reserve or in the middle? And really, without soil testing, we really don’t know.”

Bond offered similar cost savings of 15 per cent when it came to fertilizer timing, suggesting that spring fertilizer applications generally offer a better return on investment.

“I firmly believe that we need to protect that yield, and that’s what’s going to pull us through this, but we can’t protect it blindly.”