Plants and unseen soil micro-organisms all need precious space to grow. And to gain that space, a microbe might produce and use chemicals that kill its plant competitors. But the microbe also needs immunity from its own poisons.

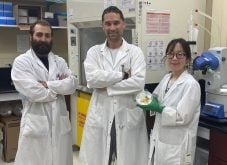

By looking for that protective shield in micro-organisms, specifically the genes that can make it, a team of UCLA engineers and scientists discovered a new and potentially highly effective type of weed killer. This finding could lead to the first new class of herbicides in more than 30 years, an important outcome as weeds continue to develop resistance.

Read Also

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

The team found the new herbicide by searching the genes of thousands of fungi for one that might provide immunity against fungal poisons.

The new herbicide acts by inhibiting the function of an enzyme necessary for plants’ survival. The enzyme is a key catalyst in an important metabolic pathway that makes essential amino acids. When this pathway is disrupted, the plants die.

This pathway is not present in mammals, including humans, which is why it has been a common target in herbicide research and development. The new herbicide works on a different part of the pathway than current herbicides. A commercial product that uses it would require more research and regulatory approval.

“An exciting aspect of the work is that we not only discovered a new herbicide, but also its exact target in the plant, opening the possibility of modifying crops to be resistant to a commercial product based on this herbicide,” said study co-principal investigator Steven Jacobsen. “We are looking to work with large agrochemical companies to develop this promising lead further.”