The North American swine industry has reached a critical juncture with sustainability challenges extending far beyond scientific solutions and now into the realm of public perception and social acceptance.

Scott Radcliffe, chair of the Department of Animal & Food Sciences at the University of Kentucky, told a recent virtual event the industry is now grappling with new societal expectations

“I think the industry is kind of at a key point right now, where we’re really struggling with things that may have less to do with science than we’d all like,” Radcliffe said during the event hosted by Agriculture and AgriFood Canada’s Sherbrooke Research and Development Centre on June 10.

Read Also

Where’s the water? RISMA knows

National soil moisture sensor network gives real-time data for Manitoba farmers fighting more frequent drought or flood.

WHY IT MATTERS: Pork production requires ‘social license’ to operate but it can be hard to square those expectations with economic and biological reality.

Radcliffe’s work has uncovered four pillars of sustainability, including economic viability, animal health and welfare, environmental impact, and social acceptance, with the latter proving increasingly challenging for producers.

“Social sustainability… is probably one of the biggest impacts that we’re seeing right now is how the public views us, how they think we’re sustainable,” he said.

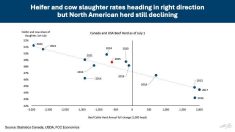

Gains offset by growth

The industry has made significant environmental improvements over the past 50 years. In the United States, producers now generate 29 per cent more pigs with a 39 per cent decrease in breeding herd size, while achieving a 33 per cent improvement in feed efficiency and doubling carcass weights.

However, these efficiency gains per kilogram of pork are offset by dramatically increased global production. Worldwide pork consumption has surged from 24 million metric tons in the 1950s to approximately 120 million today, Radcliffe said.

“We’re more efficient per kilogram, but as an industry, that footprint is bigger, and I don’t think we often like to admit that.”

Water usage presents a particular concern. While pigs themselves use water more efficiently, irrigation for crop production to feed livestock has increased by more than 200 per cent since the 1950s and 1960s.

Perception of the pork sector

Currently, Radcliffe believes society is less accepting of the swine industry’s standard business practices.

“Whether this is pork production or animal agriculture in general, I think our social license to operate is eroding,” he said. “We don’t have the public confidence we once did.”

The challenge is compounded by a disconnect between industry practices and public knowledge, Radcliffe believes. Most consumers have no farm background and don’t understand modern animal agriculture, while biosecurity measures that protect animal health also hide operations from public view.

“The general public has no idea what industry standard practices are for swine production,” he said. “And if you explain it to them, it may not help.”

He cited California’s Proposition 12, which mandated larger pen sizes for pigs despite a lack of supporting scientific data, as an example of policy driven by public perception rather than research.

Recent Danish research highlighted potential conflicts between animal welfare expectations and environmental goals. The study found that while some welfare improvements showed benefits, high animal welfare and low environmental impact are potentially at odds, Radcliffe said. Standard production systems achieved the lowest baby pig mortality rates, while free-range operations, favoured by the public, had higher mortality, the research showed.

Economic pressures mount for farmers

Economic sustainability faces its own pressures, particularly in the current global trade environment. Tariff policies could simultaneously reduce pork exports while lowering feed costs, creating complex market dynamics, Radcliffe said.

The industry must also confront the possibility of foreign animal diseases, with African swine fever representing a potential US$50-billion economic impact over 10 years if it reaches North America.

“That’ll decimate the market,” Radcliffe said. “It’ll take a long time for the U.S. industry to recover from something like that.”

Adapt or risk decline

Looking ahead, the industry must become more proactive rather than reactive to public concerns, Radcliffe believes.

“Historically, we have been reactive to things. We’ve got to get in front of this, and we are behind.”

The industry must embrace new technologies including artificial intelligence and genetic modification while improving transparency and public engagement, Radcliffe said.

“We need to figure out how to increase transparency…and we need to realize that change is inevitable.”