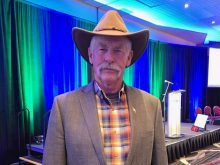

Glacier FarmMedia – David Rourke, a 67-year-old grain farmer from Minto, Man., made it clear he’s not in competition with his mother, but he’s obviously cut from a similar cloth.

After earning a master’s degree in education and then a master’s degree in nursing, Rourke’s mom went back to school in her 50s to pursue a doctorate in nursing.

Rourke got started a little later than his mom but, at 65, he began working on a PhD thesis from the University of Manitoba. The topic is sustainable grain farming with the title, “In Search of Net Positive Carbon Grain Farming in Western Canada: Innovation in Policy and Practice.”

Read Also

Tie vote derails canola tariff compensation resolution at MCGA

Manitoba Canola Growers Association members were split on whether to push Ottawa for compensation for losses due to Chinese tariffs.

The idea behind the thesis is less complicated than the title.

Why it matters: David Rourke’s operation in southwestern Manitoba is a hub of on-farm research on sustainable and profitable practices.

Rourke plans to interview farmers from the Prairies and northern U.S. Plains who want to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from cropland, store more carbon and still produce robust yields. He refers to many of these practices as “zero till plus.”

The reasons they’re pursuing those goals might be multidimensional, he noted. Maybe they’re trying to improve land for the sake of soil health and their bottom line. Maybe they’re trying to do their part against climate change.

“We do have the responsibility to feed a certain number of people … and [produce] fuel to some degree, and we have a responsibility to fix the harm we’ve done to the Earth,” Rourke said.

“This is trying to find that balance and trying to find farmers who are taking [this] seriously; to figure out, on a scalable basis, how we might tackle this responsibility.”

The premise of his thesis is to talk to producers rather than academics or idealists. He hopes to identify realistic and progressive solutions instead of fringe ideas.

“What I’m grappling with right now is how to handle all those different types of voices. I think I have to, because there isn’t a single solution,” he said.

He is now on the hunt for potential interviewees.

Net-positive grain farming?

A number of Canadian farm groups and organizations are promoting “net-zero” agriculture by 2050, in which farmers will dramatically cut fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions. Rourke thinks grain farmers can go beyond net zero.

“Agriculture has that added advantage of being able to sequester carbon into the ground…. That’s why I call it net positive.”

Rourke also has his own ideas and potential solutions to add into the conversation.

He and his wife, Diane, started grain farming in 1980, beginning with a half section of land. At the time, he was also working as a winter wheat agronomist, trying to convince farmers to seed winter wheat directly into crop stubble. In 1981, Rourke received a master’s degree for his research into zero till.

That work convinced him to try the practice on his farm, which has since grown to 6,000 acres.

The Rourkes embraced zero till for about 35 years. That changed in 2017 when they went organic and tried to merge zero till into the operation.

“There was a desire to be a little bit more self-sufficient,” Rourke said.

The farm stuck with the system for five years but, in 2022, he decided that the tillage required for organic weed control wasn’t worth the moisture lost to it.

“Whenever you till, you create kind of a micro-drought,” he said.

Today, he believes large-scale organic grain farming does not produce sufficient yields in Western Canada. It might work as a niche system, but it’s not going to work on 70 million acres of cropland across the Prairies, he added.

“Organic in this area is not really a scalable solution…. We concluded after five years that moisture is precious in Western Canada.”

Cover crops?

Rourke also has thoughts on cover crops, which are seeded to improve soil fertility and keep a living plant on a field for the maximum number of days per year.

The federal government has been promoting them as a potential solution to climate change. In 2022, Agriculture Canada announced $182.7 million in funding to encourage farmers to plant cover crops, try rotational grazing of livestock and change their management of nitrogen fertilizer.

Seeding cover crops following harvest can boost soil health and fertility under the right conditions. But in the cool and dry climate of Western Canada, cover crops are difficult.

“If we’re defining it as a crop that’s seeded post-harvest, in the fall, expecting significant growth and it’s going to have significant impact … from my personal experience, I don’t think it’s the right [approach],” said Ryan Boyd, who farms near Brandon and is an advocate for regenerative agriculture.

“We live here in a northern climate, and our biggest challenge is the short [growing] season.”

The harvest window is narrow, he noted, and it’s a challenge to fit in a seeding pass for cover crops.

“That’s not an excuse. It’s reality,” he said.

Rourke echoes Boyd, saying fall-seeded cover crops are not realistic.

“Sow that cover crop … and do it while you’re combining, and take $30 to $70 [per acre] out of your pocket and hope sometime in the future you’ll get a return on your investment?”

He wonders if another option is feasible.

Maybe it’s possible to plant a cover crop in spring, at the same time as the cash crop is seeded. Maybe the cover crop seed can be coated to delay germination. That is one concept the farmer has been playing with as part of on-farm trial plots on his land.

“It won’t germinate until about 80 days later. Then we don’t have to go back and seed [in the fall]. It’s in the ground.”

Peer-to-peer

Rourke expects that his interviews will each take two to four hours. He can make other farmers’ stories anonymous, he added, although he’d prefer to find people willing to put their name to their experiences, challenges and successes.

“I’m really curious to see what kind of innovations people have,” he said.

That shared knowledge “will get us closer to this net positive.”

Producers who want more information or are willing to share their thoughts can contact Rourke at [email protected].

– This article was originally published at The Western Producer.