Canada’s farmers will suffer if the country’s productivity crisis doesn’t improve.

That was the sobering message from Farm Credit Canada’s J.P. Gervais at the Canadian Pulse and Special Crops Convention in September.

“I’m super-enthusiastic about the long-term outlook,” said Gervais.

Read Also

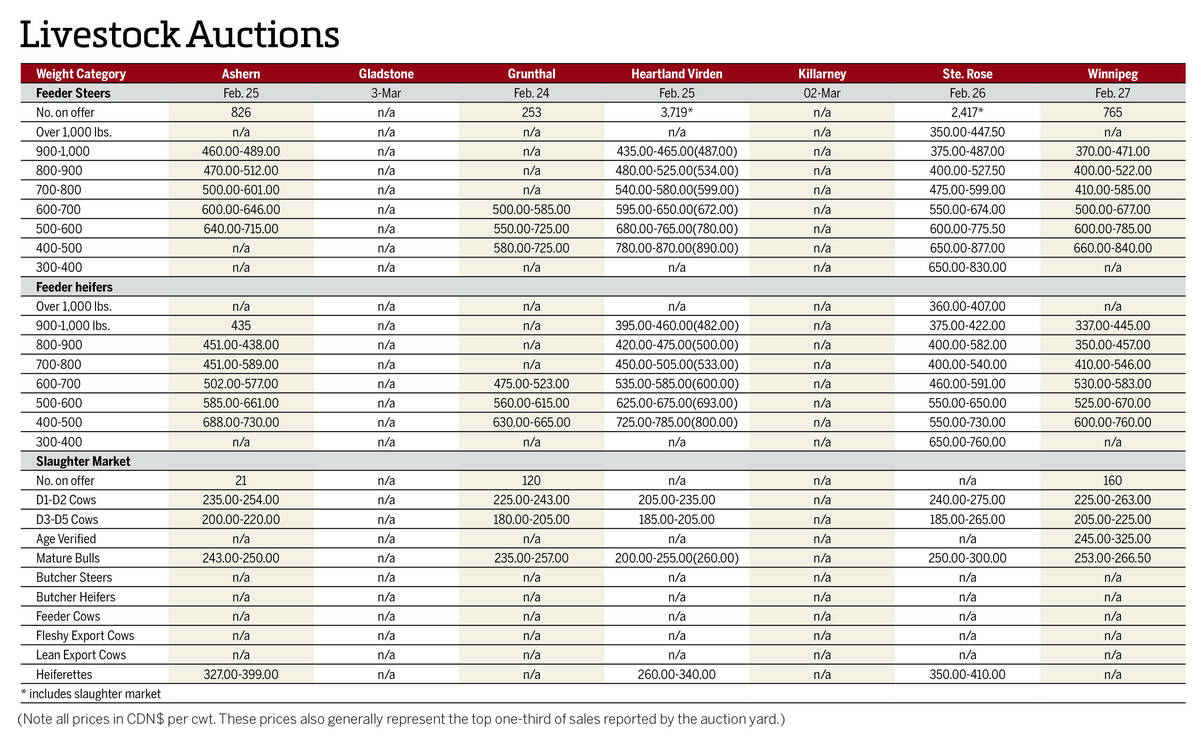

Manitoba cattle prices, March 4

Chart of weekly Manitoba cattle prices.

Why it matters: Canada’s productivity slump threatens to undermine what could be a golden future for Canadian farmers.

Canada’s agriculture industry is ideally situated and pulse crops offer the single greatest greenhouse gas emissions reduction tool that farmers have in hand, convention attendees heard. But Canada is also lagging behind the United States in productivity growth. From 2017 to 2022, Canada’s productivity grew only 3.2 per cent, compared to 9.1 per cent in the U.S.

With only the 2012 to 2017 period as an exception, Canada’s productivity growth has been weak since the late 1990s. Specific agricultural productivity growth is in a long-term slide, the reversal of a boom that took off in the 1970s and topped out by 2000.

The 1980s alone saw a 23.4 per cent gain in Canadian agricultural productivity. The 1990s were almost as impressive, at 21.9 per cent, but the next two decades saw steadily lower gains, with the 2010s at only 13.7 per cent.

If the trend continues, Gervais thinks ag may see less than one per cent growth per year in this decade.

U.S. agriculture is suffering the same problem, and has seen its productivity gains fall even more than that of Canadian ag. That helps mitigate the potential competitive disadvantage on this side of the border, but it also means Canadian farmers can’t piggyback on U.S. growers for easy productivity gains.

Canada’s export and free market-oriented agriculture sector is part of a world market and deeply integrated with the North American economy, attendees heard. In some ways, that means farmers are insulated from larger economic problems plaguing Canada.

To a degree this is true of productivity, which will see Canadian farmers employ machinery, management techniques and innovations that arise south of the border or anywhere in the world. Canadian farmers aren’t trapped within a closed market.

They are, however, reliant upon the rest of the economy, from labour to services to new products created specifically for Canadian farming conditions. Gervais noted Canada’s below-average research and development investment by the private sector compared to most other advanced nations.

Gervais would like to see Canadian ag get back to two per cent per year productivity gains, which held in the 1990s and 2000s. That would mean an extra $3 billion in farmers’ pockets every year.

Is it the regulatory regime that’s strangling growth? Laws, rules and other complications can discourage people from investing their money.

That topic will more than likely be discussed at length soon in Calgary. The University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy is holding what’s it’s calling Canada’s Productivity Summit, which will focus on many of the concerns raised to pulse and special crops growers. That event runs Oct. 16 and 17.

Productivity isn’t a sexy topic that gets people chatting. It sounds dull. But, Gervais argued, it is “the most critical topic for the long-term outlook for the industry.”