A headline in the Aug. 15, 2013, issue of the Western Producer was an attention-getter: Destroy clubroot before it destroys you: expert.

The headline was a bit sensational, but it did reflect the thinking at the time. Scientists, agronomists and canola growers were extremely worried that clubroot would spread across the Prairies and devastate Canada’s canola industry.

WHY IT MATTERS: Canola growers continue to be on the watch for clubroot, but co-ordinated efforts, research and new tools have helped keep the disease from exploding as many worried in the last two decades.

Read Also

Farm Credit Canada forecasts higher farm costs for 2026

Canadian farmers should brace for higher costs in 2026, Farm Credit Canada warns, although there’s some bright financial news for cattle

The paranoia about clubroot wasn’t short term.

It lasted from 2003, when the first case of the soil-borne disease was found near Edmonton, to the middle of the 2010s.

Stephen Strelkov, a University of Alberta plant pathologist, was a key player in the research to understand the disease, which causes swellings or galls to form on the roots of canola plants.

A severe clubroot infection in part of a canola field can cause a 100 per cent yield loss.

Like many others, Strelkov was very concerned about clubroot and what it could mean for canola production.

“Fifteen years ago it was like, ‘Oh my God, what’s going to happen, is this going to be a … major issue’? ” Strelkov said from his office in Edmonton.

“When the first cases were detected on canola in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, that maybe we might have a similar scenario (to central Alberta).”

Autumn Barnes, research manager with Alberta Canola, remembers the event that prompted the Western Producer article and its eye-catching headline.

It was a clubroot disease meeting in Brooks, Alta., during the summer of 2013.

“At that time, our only ‘real’ management option was sanitation, and there were a couple varieties with limited resistance available for farmers in central Alberta,” Barnes said.

Nowadays, 12 years after that headline, the situation has completely changed. Clubroot has become a manageable risk and something that’s almost invisible in Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“As in 2023 and 2024, no new visible clubroot symptoms were recorded via the clubroot monitoring program in 2025,” said a preliminary canola disease survey for Saskatchewan, published this fall.

In Manitoba, no symptoms were found on canola plants in a disease survey of 117 fields in 2025.

The lack of detections suggests that clubroot is not a massive problem in Western Canada.

“It’s not the same huge risk that we were thinking, 15 years ago,” Strelkov said.

What happened?

After the initial detection of clubroot near Edmonton, it became clear that the problem was much larger than one field. Symptoms of the disease were soon found in hundreds of Alberta’s canola fields.

By 2007, several Alberta counties had restricted the growing of canola on infected fields.

In Leduc County, canola was permitted once every five years to control the spread of clubroot.

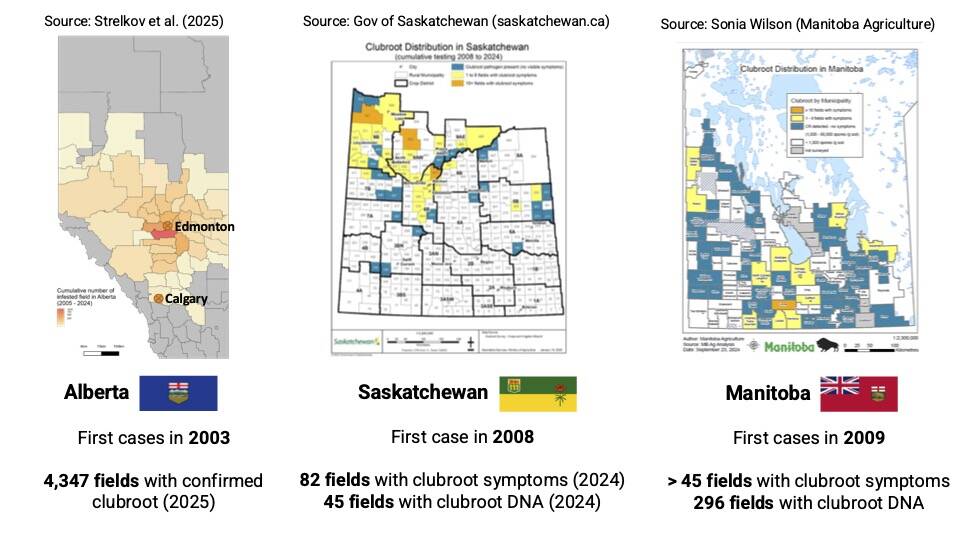

Outside of Alberta, clubroot spores were found in Saskatchewan in 2008 and one year later in Manitoba.

There were worries that clubroot couldn’t be contained and Prairie farmers would have to grow canola on a longer rotation to keep the disease in check.

However, farmers, agronomists, scientists and canola seed companies responded in a co-ordinated effort to tackle the risk.

A combination of factors made a difference:

- The gap in time between detections in Alberta and other provinces

- Pioneer Hi-Bred developed a clubroot resistant canola hybrid that hit the market in 2009 and 2010

- Farmer awareness — growers became more vigilant about sanitizing equipment and moving machinery to prevent the spread of clubroot infected soil from field to field

- Government investment in equipment to detect clubroot DNA in the soil before the disease became a problem

These factors and other actions helped prevent the buildup of clubroot spores in new fields across the Prairies.

“Much earlier ability to recognize the symptoms and take preventative measures,” Strelkov said, noting farmers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba began seeding clubroot resistant varieties in the absence of clubroot.

“(If) you’re starting to grow resistant varieties, pre-emptively, that makes it a lot more difficult for the pathogen to build up.”

For Barnes, the crucial bit was a targeted investment in clubroot research. Grower groups such as Alberta Canola invested to identify resistant traits, which led to commercial varieties with a diversity of resistant genes.

“It is incredible to think that virtually every commercial canola variety available in the Prairies (now) has some type of clubroot resistance package,” she said.

“In addition to genetic resistance, funders across the Prairies have leveraged resources to understand clubroot pathotypes, options for management (such as liming), testing and general disease biology.”

The clubroot pathogen does prefer acidic soil, which led to the theory that the disease is less problematic in Saskatchewan and Manitoba because low pH soil is less common in those geographies.

That theory is somewhat true and somewhat false, Strelkov said.

Clubroot spores do better in acidic soils, but the disease can take hold and cause damage in neutral or higher pH soils.

“If your soils are acidic, you’re at more risk,” he said.

“(But) given the right conditions and short rotations, clubroot can become an issue in fields that wasn’t as acidic.”

Canola with clubroot symptoms is rarely detected in Manitoba or Saskatchewan disease surveys, but the disease is still top of mind for canola growers in parts of Alberta.

More than 4,300 canola fields in the province have had symptoms of clubroot on canola plants. In the other Prairie provinces, the total is 127.

Plus, soil samples in Alberta have detected millions of spores in one gram of soil and new pathotypes of clubroot have appeared.

That’s concerning, but early detection allows the canola industry to identify the new variants before they run wild.

Canola is still grown in areas with a history of clubroot infections, and average yields in Alberta were nearly 43 bushels per acre in 2025, close to historical highs.

That’s an incredible success story, considering the clubroot fears during the 2000s in Alberta.

“In 2003, 2004, 2005, we were thinking, ‘Will we be able to grow canola, beyond once every seven years’?” Strelkov said.

“So, even here, it’s being managed quite well. … If we do our work and stay ahead of it, I do think it’s a very manageable problem.”