The stress of extended flooding losses followed by a harsh winter prompted Scott Kolomaya to make a tough decision in the spring. He sold three-quarters of his cattle herd.

His hayfields were flooded in 2011 and had not yet been returned to production. After a long and bitter winter, he was running short of feed.

“I was basically forced to sell at that point,” he said. “I didn’t have the hay and the winter was so harsh I decided I’d better start moving them while I could. Decided to back off on the amount of work I had because I was under stress.”

Read Also

Pig transport stress costs pork sector

Popular livestock trailer designs also increase pig stress during transportation, hitting at meat quality, animal welfare and farm profit, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada researcher says

His hay and pasture was still starting to grow again this spring when this year’s flood hit, inundating several hundred acres on his farm.

Kolomaya is not alone. The flood waters are receding but cattle farmers in affected areas of Manitoba face possible feed shortages going into the next winter. If the frost comes early this year, cattlemen may need to choose between paying more for outsourced feed or selling part of their herd.

Ted Artz, a cattleman from Pierson who serves on the board of directors for the Manitoba Beef Producers, says the province’s beef industry has faced a lot of hardships in the decade since BSE — better known as mad cow disease — crippled the industry in 2003.

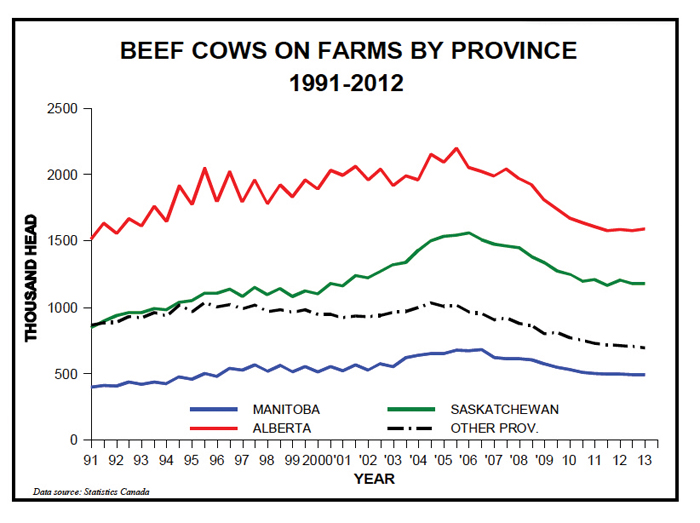

According to a recent report by the University of Manitoba on the Manitoba cattle and beef industry, the province’s number of beef cows fell to 493,700 head in 2012 — the smallest count since 1993.

Artz says less young people are entering the business. “The majority of producers in our areas have too much grey hair,” he said. “We are getting older. And the young people who might want to get in have got very good oil jobs, outside income. And it’s pretty hard to give that up.”

This year Artz could also face feed shortages. A long winter meant he had to dip into his reserves. He was able to seed in mid-July, but his crops are still green. He’s hoping frost holds off until late September. If he doesn’t, he might be forced to sell 30 to 40 per cent of his herd.

Artz said he wants to protect the business for his son who will eventually take over. “If we’re short of feed I will sell the cattle we need so my son can continue,” he said.

Debbie McMechan, a grain and cattle farmer and councillor for the RM of Edward, said people are exhausted from the cleanup and repairs to fenceline following the flood. Her town, Pierson, declared a state of emergency on June 5 after overland flooding rushed over the small southwestern Manitoba town and nearby farmland.

Her husband bought a bale wrapper and a baler this year so he could collect the hay earlier than usual. Some neighbours are getting creative — baling wild oats that have taken over the fields once full of cash crops.

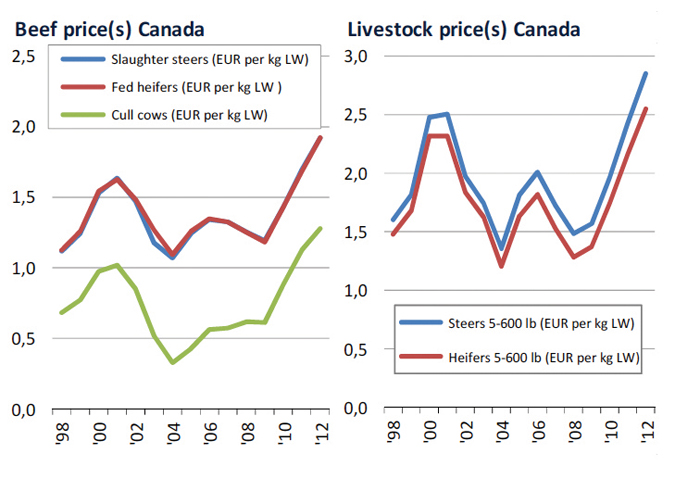

“If you are a cattle farmer there is a lot of talk about quitting,” she said. “That is due in part to the prices are pretty good right now.”

Her husband won’t quit because they are lucky to have some high pasture that hasn’t been hit by flooding. But she’s not sure yet whether they’ll have enough feed to make it through the winter.

The province as a whole isn’t facing feed shortages, according to Craig Thomson, vice-president of insurance operations at MASC, although he noted overall forage production numbers aren’t tallied until November.

“Probably half the province looks like they have average to above-average forage,” he said.

Whether flood-affected farmers decide to outsource their feed will depend on the price. Buddy Bergner, an auctioneer from Ashern, another flood-affected area, said cattle farmers he’s spoken to are getting creative with what they feed their cows this year.

“Some guys are looking at buying grain and looking at bringing in their cattle through that way,” he said, “with some grain and then roughage, like corn or barley.” He said older cattle farmers are considering retiring.

“The market is good and they can see cash in their hand,” said Bergner. “No work and no risk.”

Melinda German, general manager with the Manitoba Beef Producers, said she’s discouraged to hear people are thinking about quitting. Areas in Manitoba unsuitable for grain cultivation grow forage successfully, making them ideal for cattle production. She said exciting new opportunities are also opening up in the industry.

“A lot of international trade markets are coming available that we’ve never had before,” she said. “But if Manitoba is losing its farmers and we’re losing the number of beef cows we have here, we’re not able to capitalize on all those opportunities like the rest of the country.”

Kolomaya is not ready to quit yet. This year the third-generation farmer celebrates his farm’s 100th anniversary. But this winter he may face more tough choices about whether to winter his cows or sell them.

“I have to decide what direction I want my life to take because I have done this my whole life. I haven’t done anything else,” he said. “There’s a lot of jobs I can do, but do I want to do them? I’ve been my own boss for so long now. It’s not the same when you’re not making that decision based on your own will to decide.”