Not every beekeeper wants Canada to reopen trade for packaged bees from the United States, but when it comes to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s (CFIA) recent dismissal of Canadian beekeeper recommendations intended to address risks of the practice, three industry experts agreed: it stinks.

WHY IT MATTERS: The question of U.S. bulk packaged bees is divisive in the Canadian beekeeping industry, with those against wary of imported pest issues, while those in favour point to recent devastating winter losses and the need to restock.

A number of provincial beekeeping groups, Manitoba and Alberta included, have spent years asking the CFIA to reassess the risk of U.S. bulk bees — defined as units of two or three pounds of bees, plus a young queen.

Read Also

Farm trade policy pundits lay CUSMA odds

What’s the future of Canada’s free trade agreement with the U.S. and Mexico? Policy experts try to read the stars on the issue

Canadian regulations haven’t allowed those shipments since the 1980s, citing risks like American foulbrood, varroa mites, Africanized genetics and small hive beetle. Reassessments in 2013 backed up the ban. A portion of the beekeeping industry agrees.

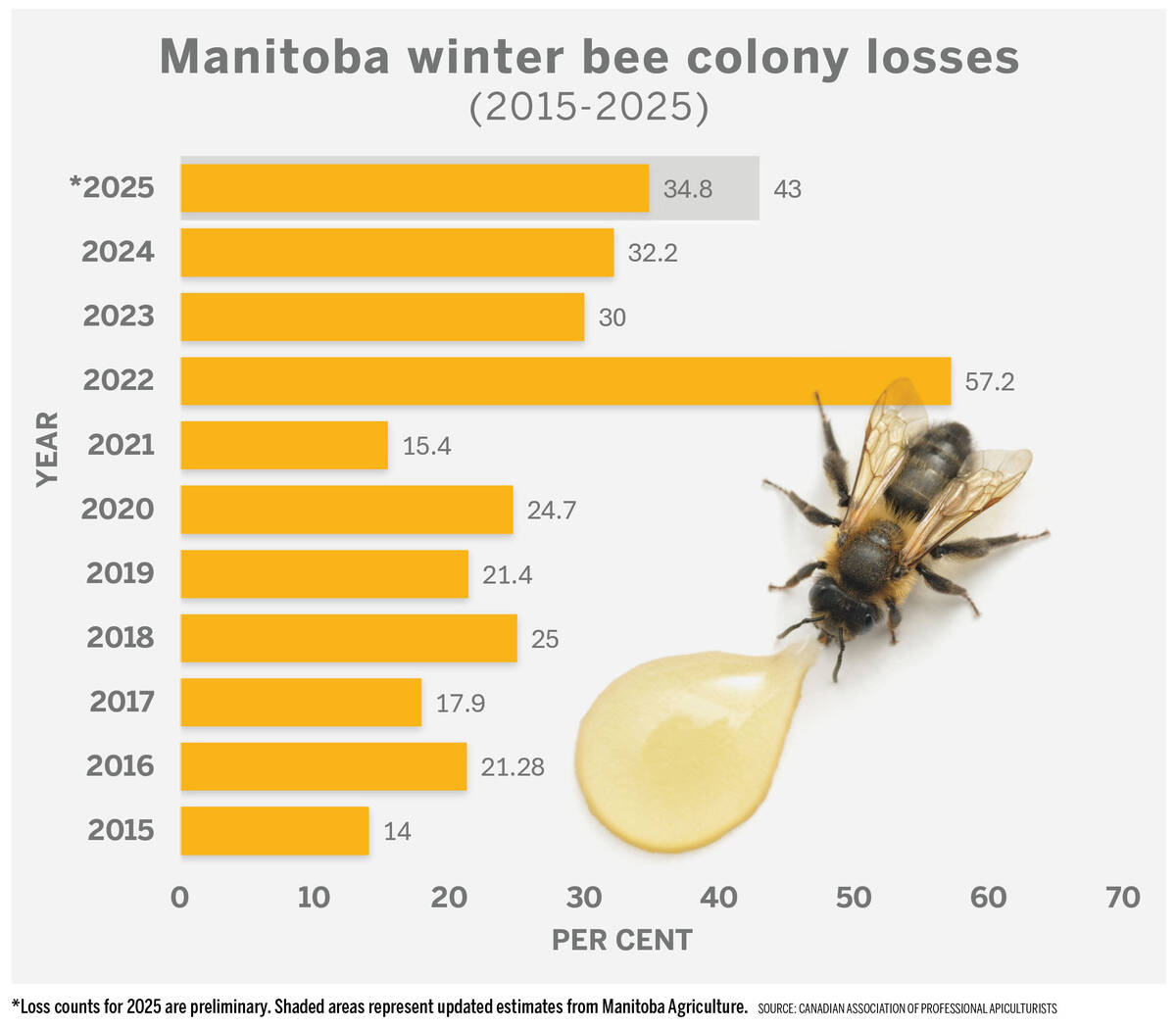

Others, particularly among the big beekeepers of the Prairies, argued those risks could be mitigated, that the last reassessment was outdated and that, frankly, they need the bees. Manitoba, for example, is coming off its fourth straight winter of bad bee loss. Manitoba Agriculture recently put those colony loss numbers at 43 per cent.

Splitting hives to recover those numbers reduces honey harvest, and issues with sufficient restock options has been a hot topic since the pandemic, when grounded air traffic complicated Canada’s ability to source bees from approved markets.

Last year, the CFIA invited industry to submit ideas on how the risks of U.S. packaged bees might be addressed. When the agency released its response early this month, those proposals were roundly smacked down.

“After careful evaluation of all input received, the CFIA concluded that no feasible, scientifically-supported (sic) mitigation measures are currently available to bring all identified risks within acceptable levels,” a further statement put out by the agency Aug. 6 read.

“As a result, Canada will maintain its current import restrictions and will not permit the importation of honey bee packages from the United States at this time.”

Frustrated industry

Mike Paradis, Canadian Beekeepers Federation president and a seventh-generation beekeeper from Peace River, Alta., was disappointed, but not shocked by the CFIA’s dismissal.

“It was no surprise to me that they were going to come out with that,” he said. “I was hoping that there was going to be some understanding and common sense in that decision, but there was none — none at all.”

Industry suggested, among other things, a limited regional trade strategy allowing shipments from areas of the U.S. where Canada already gets queens, like northern California (U.S. queen bees, which do not come with hive material, are allowed under current regulations), evaluation of the impact on inter-provincial movement, transport inspections upon entering Canada, applying current import conditions of queens for packaged bees and the utilization of best management practices post-importation.

In several cases, the CFIA noted that proposals relied on “further research” rather than active risk mitigation measures. Others, the agency dismissed as lacking in robust scientific backing or improperly addressing the risk in question.

Regional trade strategy insufficient: CFIA

The proposed pilot trade strategy with northern California was among the more prominent suggestions by industry. Because of the existing queen trade, there’s an existing quarantine procedure. Beekeepers argued a similar arrangement could easily be extended for packaged bees, Scarlett noted.

However, the CFIA said the submission did not include a necessary zoning proposal from the United States Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS).

“The exporting country must be able to demonstrate, through detailed documentation provided to the importing country, that it has implemented the recommendations in the Terrestrial Code for establishing and maintaining a zone,” read the document.

There’s a problem with that, says Rod Scarlett, executive director with the Canadian Honey Council: APHIS lacks the manpower.

“They would have to be the ones that would do the inspections and the formal sign-off that ‘Yes, these protocols were followed,’” he noted.

In response to statements that queens are already exported from northern California to Canada, the CFIA said the assessment “clearly determined honeybee packages present a higher risk of importing identified hazards than caged queens.”

It also noted that current import conditions for queens were “insufficient” to mitigate the package hazard risk. This was also corroborated in the mid-2010s risk analysis, it read.

Industry, agency clash

Kevin Nixon, manager of Nixon Honey in central Alberta’s Red Deer County, calls the CFIA’s response “frustrating” because beekeepers don’t have much clarity on what the agency is looking for.

“We’re beekeepers. We’re not scientists. And we have ideas in our mind that we think would mitigate risk,” he said.

“But obviously, from a scientific perspective, they’re finding reasons that it’s not, so why not put a group of 10 or 12 people together, sit around a table and be like, ‘How do we figure this out? What’s it going to take to mitigate the risk?’”

Jeremy Olthof, manager of Tees Bees in central Alberta said, “It comes down to what’s more important: potentially healthier bees but a smaller industry, or a growing industry that will constantly rely on imports and the health challenges that can result.”

The Canadian beekeeping sector has been growing substantially over the past seven years, increasing from 10,523 beekeepers in 2019 to 15,430 in 2024, according to Statistics Canada.

Scarlett also wasn’t surprised by the federal response. Apiarists’ faith in their own observed science versus CFIA’s demand for peer-reviewed national scientific data was bound to create a negative outcome for beekeepers, he said.

On the other hand, “There’s very little actual national scientific data that they could rely on to change any of the opinions (in) the risk assessment itself.”

No weight for financial health

Paradis does not see the CFIA ever changing its stance on the industry’s concerns whether it offers the level of robust science the agency wants or not.

“They have let it be known to the industry multiple times the financial health of the industry is not (their) concern.”

That is, in fact, a point brought up in the summary.

“The CFIA does not have a duty of care to protect the economic interests of stakeholders,” the document read. “The CFIA’s regulatory mandate under the Health of Animals Act and regulations is to help protect Canadian animal health, which includes the health of the Canadian honeybee population.”

As for beekeepers on the “nay” side of U.S. package imports, Nixon suggests they’re fairly pragmatic.

He’s heard some express concerns that the practice could lead to U.S. exporters sending live hives in large quantities, in the process putting existing Canadian pollination contracts at risk.

Nixon does not discount this apprehension, but he doubts the reality will reflect those fears.

“(They say) people would come in and undercut or overstock an area with bees where currently honey production is, but if an area was overstocked, it would decrease the overall production per hive, so I don’t know if it would ever lead to that.”

U.S. bee problems already here

The CFIA focused much of its summary on the risks of Africanized bees and small hive beetles entering the Canadian ecosystem.

Paradis takes a dim view of these concerns. He wonders why Africanized bees are so feared when the importation of queen honeybees from the U.S. has been going on for decades.

“The Africanized bee follows the genetics of the queen. And further to that, a queen breeder in the U.S. or anywhere never breeds on genetics. We all breed on traits. Is it a good honey producer? Is it gentle? Does it create massive amount of brood? Is it disease resistant?”

Both Canada and the U.S. also have more or less the same disease and pest profiles.

“We have every disease that they’ve stated in there,” Paradis said. “(They’re) right across Canada, every bloody one, and a few of them that they don’t have in the U.S., we have a few extra here because of the importation that we’ve been doing.”

This is largely true, but there are some nuances, said Nixon.

“We both have varroa mites and (the U.S. has) had mites that have become resistant to the main treatment that we have … We’re now starting to see resistance in the treatment we have for the grower here as well.

“American foulbrood is present on both sides of the border and we’ve had resistant American foulbrood here. I don’t think we have a big problem with it in Canada, but it is around and there are flare-ups every once in a while.

“Small hive beetle is one that’s pretty common in the (United) States and we’ve had a few incursions of it come into Canada in the last 10 years, but they don’t seem to establish here in our climate. There were incursions in both B.C. and southern Ontario and they quarantined things and managed it.”

Favoured trade countries disputed

The CFIA allows import of packages from a handful of countries including Australia, New Zealand, Chile, Ukraine and Italy. Paradis’ biggest beef with the CFIA’s chosen countries is that their beekeepers’ crop years are at odds with Canada’s.

“They’re exactly on the complete opposite side of the world. Our summer is their winter, our spring is their fall. So (when) they’re coming off of their honey crop, they don’t have the ability to give you a fresh young queen,” he noted.

“You can say, ‘Yeah, but they haven’t been exposed.’ Well, that’s exactly the problem. They haven’t been exposed to our disease profiles, so they’ve never built up any kind of immunity or any kind of resistance to these problems compared to the U.S. bees.”