Manitoba’s independent canola trials this year had a real problem with verticillium.

All but one of the eight sites tapped for the 2025 Canola Variety Evaluation Trials (CVET), scattered across various growing regions in the province, struggled with high levels of the disease. Only Morris, the eastern-most location, recorded low levels of the disease.

WHY IT MATTERS: Manitoba has been ground zero for verticillium stripe on the Prairies since it was found here in 2014.

Read Also

Foggy grain market predictions for 2026

Many factors are pushing and pulling at grain markets as farmers leave 2025 behind and start considering what 2026 will bring.

The fungal disease has been a tough one for agronomists and producers to crack. There aren’t chemical options for the soil-borne disease and, while seed companies are chasing the carrot of genetic tolerance, a truly resistant variety has yet to hit the market.

On top of that, longer rotation, a common go-to management strategy when it comes to other soil-borne diseases, is less successful against verticillium, said Manitoba Agriculture oilseeds specialist Sonia Wilson.

“Rotation alone cannot solve this problem, as the microsclerotia can potentially remain dormant in soil for up to 10 years, similar to verticillium wilt,” she warned.

Verticillium everywhere

It’s prevalence at CVET sites aligns with what Wilson and her colleagues are seeing across the province.

”Verticillium stripe is being increasingly recognized in fields across Manitoba,” she said.

Provincial survey results show the disease has been climbing since it was added to assessments five years ago. In 2025, 73 per cent of canola crops in Manitoba showed symptoms, with an average incidence of 41 per cent in fields where it was present.

Understanding the disease pattern

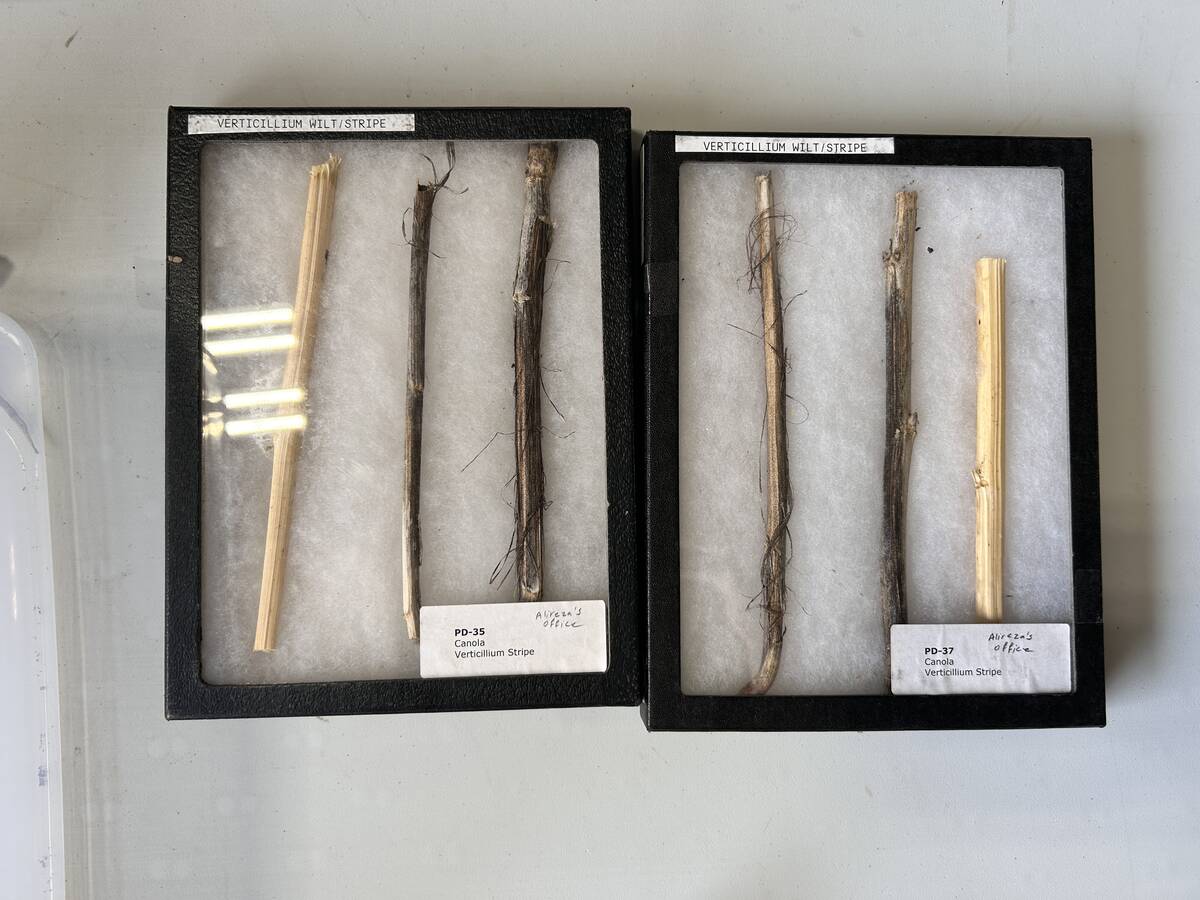

One big problem of verticillium is how hard it is to tell apart from blackleg, a disease endemic to Manitoba canola fields.

Early symptoms of verticillium in canola can resemble striping on the stem (brown streaks on a green stem), starting three to four weeks before harvest, Wilson said.

“Later symptoms show shredding of the stem and, when the stem is peeled back, a grey colour (or microsclerotia).”

Wilson’s research has noted that the A1/D1 lineage of verticillium prefers brassicas like canola.

“It’s important to be aware of its presence, effect in your field, and understand how current and future management strategies can protect against its impact,” she said.

However, research is still emerging on the actual yield impact.

“The most recently published paper (showed) there was a large range of between 17 to 83 per cent impact on yield in single plants due to verticillium stripe, but that this did not translate to the same yield impact at a plot level,” Wilson said.

Advice for 2026

Wilson’s advice heading into the 2026 growing season is for producers to talk to their seed companies and reps about internal company scanning of varieties for tolerance to verticillium stripe. They should also mark down fields with high verticillium pressure and send in samples for confirmation.

She also noted current research looking for ways to help producers in the fight against verticillium stripe. That work is looking at topics like potential genetic resistance and the impact of straight cutting compared to swathing, environmental conditions, blackleg, and more, Wilson said.

“The focus of stakeholders across the canola industry is on funding research to answer these questions and on providing management strategies for this disease,” she said.