A lot has changed since 1959, when Nutrien produced and shipped the first 1,000 tonnes of potash from its Patience Lake mine east of Saskatoon.

Back then, the price of potash was around US$50 per ton. It is six times that value today, and this is a down year for prices.

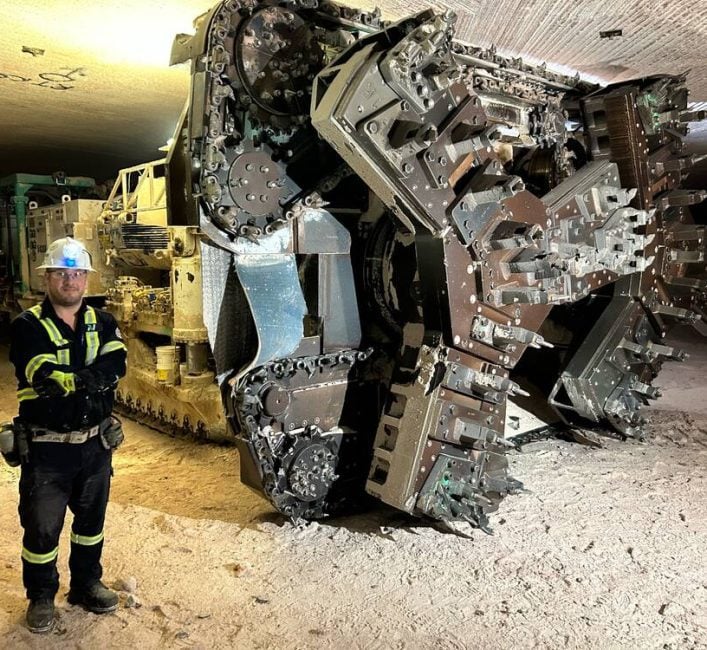

Things that haven’t changed much in the last 65 years (see video here) include the boring machines used to excavate the mineral. They’re more sophisticated now, but the technology is essentially the same.

Read Also

Glufosinate-resistant waterhemp found in U.S. Midwest

Kochia may also be on the road to Group 10 herbicide resistance, which would be a serious blow to Prairie farmers and canola growers, warns weed scientist.

The big advancement in the mining process is conveyor belt systems, rather than trolleys, that bring ore to the surface.

Then there’s the shear scope of the operation. Nutrien’s mine at Allan, southeast of Saskatoon, stretches 20.8 kilometres north to south and 14.8 km east to west. The furthest mining face is located 19 km from the shaft, a 60-minute drive on the mine’s underground road system, which is one kilometre below the Earth’s surface.

There are 90 km of conveyor belt lines sprawling underground, with skips that hold 54 tonnes of payload. The shaft production hoist uses a 12,200-horsepower motor and operates at speeds up to 3,600 feet per minute.

The mill can produce more than 12,000 tonnes per day of finished product. More than 70 rail cars can be loaded in a 12-hour shift, which amounts to 7,200 tonnes of red and white potash.

That’s all from only one of the company’s six Saskatchewan mines.

Going global

Nutrien is the world’s largest potash producer, with 20.6 million tonnes of annual nameplate capacity, although actual production is closer to 15 million tonnes.

It has 5,900 owned or leased rail cars that transport product either to the United States or to ports, where it is sent to more than 40 overseas markets. The company is the largest private sector employer in Saskatchewan, with a workforce of more than 4,200.

Les Frehlich, general manager of the Allan mine, said the future of the potash sector remains bright.

“The outlook is for (demand) to grow annually as the world population increases and diets change,” he said during a recent media tour of the facility. “That’s going to continue to drive potash demand.”

The world’s population is growing at a rate of 0.87 per cent per year, but there is also a rising middle class leading to more meat consumption, which requires more feed crops such as corn, a heavy potash user. He anticipates potash demand will continue growing by two to 2.5 per cent per year.

Market waves

Josh Linville, a fertilizer analyst with StoneX, thinks that demand outlook is spot on. However, he worries about the other side of the balance sheet.

“I’ve always tried pumping the brakes on saying ‘oversupplied,’ but I think it’s going to be very, very well supplied,” he said.

Potash is selling for about $300 per ton today, which is below the 10-year average of $350 to $380. Prices shot well above $1,000 at the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“There was a concern worldwide around potash supply,” Frehlich said. “Some countries started to stock up on potash, and that drove prices up.”

The fear was that Russia and Belarus wouldn’t be able to get product to market, but the logistical quagmire did not materialize, and the market now has ample supplies.

Frehlich said every dollar counts for a mine such as Allan.

“It doesn’t take much to make a difference when you’re making three million tonnes per year,” he said.

The company as a whole sold 13.2 million tonnes of potash in 2023, generating $3.76 billion of revenue, which was less than half the amount earned the previous year when the average price was 55 per cent higher.

Various companies announced a string of new projects back in 2022 when prices were at record-high levels. A lot of those plans have stagnated now that prices have plummeted, although some are still underway.

BHP Billiton’s US$10.5-billion project in Jansen, Sask., is expected to start production in late 2026. Once fully ramped up, it will become one of the world’s largest mines, producing 8.5 million tonnes per year.

EuroChem has started the second construction phase of its Usolskiy Complex in Russia, which will add 1.8 million tonnes of production to that plant by 2027.

Asia-Potash International, a Chinese company, is investing $4.3 billion in a potash mining venture in Laos, which could produce five million tonnes annually by 2025, and as much as 10 million tonnes down the road.

Linville said North American farmers are often sitting on pins and needles when it comes to sourcing nitrogen and phosphate from war-torn or politically volatile regions of the world.

“Potash is one we don’t need to worry about because we have it here at home, and that’s a huge, huge relief,” he said.

Canada exported 23 million tonnes of potash in 2023, followed by Russia’s 11 million tonnes and Belarus’s five million tonnes, according to Global Trade Tracker. Total global exports amounted to 54 million tonnes that year.

Brazil was the world’s biggest importer in 2023, purchasing 13 million tonnes, followed by China at 12 million and the U.S. at nine million tonnes.

About one-third of Nutrien’s potash is sold in North America, most of it shipped directly by rail to customers in the U.S. Only a small amount is used in Canada.

Soil in Western Canada is already rich in potash, and Frehlich noted that many local crops don’t need as much compared to crops like oil palm, rice or corn. The latter crop took up 643,000 seeded acres in Manitoba last year, counting silage corn, but is a minor crop in the western Prairies.

The remaining two-thirds of Nutrien’s potash is sold offshore. China, India, Brazil and Southeast Asia are the biggest overseas customers. The potash is moved by rail to ports, where it is exported by Canpotex through terminals located at Vancouver, Portland, Thunder Bay and St. John’s.

Potash types

Justin Boehm, mill maintenance superintendent at the Allan mine, said the facility sells four types of fertilizer. Red standard is the most popular product, accounting for 53 per cent of the mine’s annual production. It is hand applied in markets such as Indonesia’s palm oil sector.

Granular red fertilizer is getting more popular as farming becomes more mechanized around the world. It accounts for 33 per cent of the mine’s production. White soluble product is 99.8 per cent pure potassium potash. It makes up 10 per cent of the mine’s annual production.

“That’s sold to our industrial customers, and they’ll repurpose that into several different types of products, including pharmaceuticals, food-grade potassium and those kinds of things,” said Boehm.

White chiclets are made for customers of white potash who don’t want any type of anti-caking agent applied to their fertilizer. It accounts for four per cent of production.