Fall soil sampling can be supercharged using tips from the Canola Council of Canada. The big ones include collecting a lot of sub-samples in each field, tapping soil depths and sampling known unproductive acres.

Why it matters: With the 2024 crop mostly in the bin, it’s time to think about next year’s fertility.

It’s typical to collect one benchmark composite sample based on a field’s most productive acres. However, the council says that if producers want to get the most bang for their fertilizer buck given prices, they should refine mid-slope soil sampling and target lower-producing acres.

Read Also

AI app promises Prairie farmers better insect scouting

A new app, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven and developed on the Prairies, is expected to help farmers identify and manage pest and beneficial insects.

“It’s really about gaining as much knowledge as possible to make the best decision possible,” says Warren Ward, agronomy specialist with the council.

“Everyone’s going to have a different level of how they’re going to manage their fields, right? So, for a lot of people, that one blanket rate is what they’re using because that’s what their equipment and logistics have determined is what works for them.

“But if someone is looking at trying to step their game up a little bit, or go to that next level of nutrient management, then that’s where those targeted samples come in.”

It won’t be free, it’s more work and there will be extra lab fees, but Ward argues that the return on investment can be worth it.

“There is a cost to soil sampling, but when we look at the price of fertilizer, it’s relatively small compared to that. If we are improving the management of a costly input like fertilizer, then I think the benefit really outweighs the cost.”

Fall is a good time to conduct soil sampling, says Ward. It offers a more flexible timeline to make purchase decisions and determine spring nutrient rates for each field. Fertilizer is also generally cheaper in the fall.

On the flip side, it’s a long time from fall sampling to the next crop, and there are months of winter and snowmelt in between. Samples in spring offer a more immediate assessment of nutrient needs.

Mixing it up

When developing an effective primary composite sample, the council recommends using 12 to 20 sub-samples (or cores) collected from a field’s most productive areas, usually at mid-slope. This composite can help growers select an appropriate fertilizer blend and rate that matches these productive areas, says Ward.

He suggests dividing each core into two or three soil depths and placing each in a separate container. He suggests depths of zero to six inches, six to 24 inches or a three-way split of those depths, plus one from 12 to 24 inches down.

Don’t neglect that 24-inch sample, he adds. Doing so can miss nutrients like nitrogen and sulphur.

“Certain nutrients are mobile in the soil, nitrogen being one of them, and nitrogen (is) our largest input expense for fertilizer. So by having that knowledge of what’s at depth for nitrogen, (that) can help give a better picture.”

Once cores are divided, blend each group to create one composite sample per depth. Place each in its own sample bag before submitting them to a lab.

Looking further than mid-slope

As effective as mid-slope composite sampling can be, it omits useful information that can drive a broader range of management, says Ward. Mid-slope composites don’t include data from low production acres, hilltops or heavily lodged areas.

That’s where targeted samples come in. For example, a field area might be higher in organic matter, which changes the nutrient dynamics and affects lodging risk. Over-fertilization might be an issue.

“It may be possible to reduce nitrogen rates in that area,” Ward says.

Hilltops and other high ground often contain low organic matter and moisture, reducing yield. Targeting those acres may reveal other causes.

“Perhaps low sulphur, or some other nutrient shortage, is also a factor in lower canola yields. Some targeted sulphur could help hilltops.”

Salinity is often considered the culprit when low areas fail to yield, but what if the true offender is critically low soil potassium? You won’t know until you test, says Ward.

“By targeting some of those soil samples, in addition to that one composite sample for the field, there’s maybe some more information that you can gather and some management decisions that you could make based on that.”

He warns farmers to avoid mixing their composite and targeted samples.

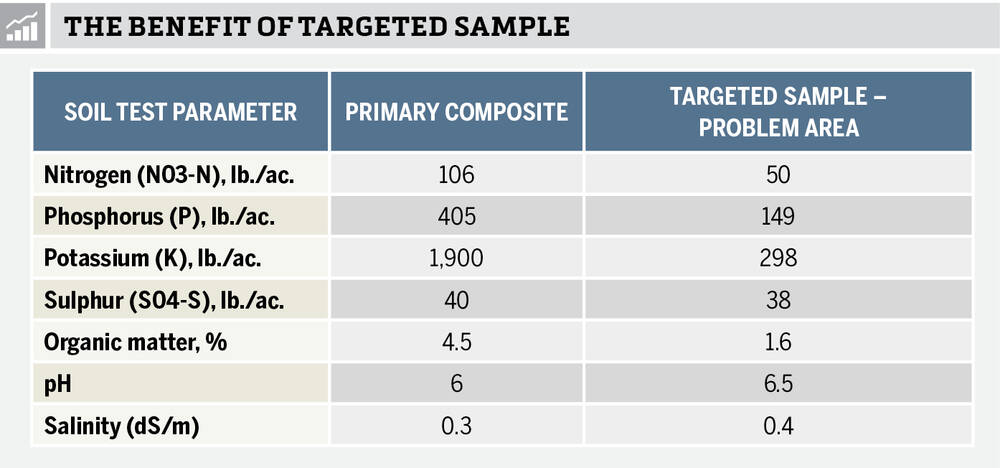

“You can’t blend samples from low-producing areas into your primary mid-slope composite. The resulting average will produce soil test results that are almost useless.”