Canadian consumers may assume a maple leaf on their groceries means the food is Canadian. That’s not the case, economist Marnie Scott warns, and confusion is hurting both shoppers and farmers.

“There’s no official logo for Canadian food products, and a maple leaf on a product does not mean it’s Canadian,” said Scott during the Manitoba Farm Women’s Conference in Brandon Nov. 17-19.

WHY IT MATTERS: “Buy Canadian” has become a rallying cry for politicians and the public over the past year since tariffs, trade protectionism and U.S. President Donald Trump’s 51st state comments hit the limelight.

Read Also

Mandatory holiday joy a valid struggle

Christmas may not be that jolly for everyone. Farm family coach Kalynn Spain suggests those struggling with over-the-top joy during the holidays instead aim for “fulfilled” or “content.”

Scott noted that the stylized maple leaves often seen on packaging are marketing, not placed as an origin claim.

“They’re trying to get you out there to buy that product without really knowing what it means,” she said.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) website also notes that there is no agreed upon logo for Canadian products. A maple leaf may indicate a Canadian company, a Canadian standard or Canadian labour, the agency says, but not necessarily Canadian ingredients. The CFIA recommends checking any accompanying claim statement on the package.

Canadian farmers lose out when “maple-washed” labels hide what really came from Canadian farms and food processors, Scott said. She urged consumers to buy the real thing.

Determining that real thing though isn’t always intuitive, and requires a level of understanding and effort on the part of the consumer.

Canada does have rules around products that can be labelled as “Made in Canada” versus a “Product of Canada,” but the average customer may not know the difference.

According to the Competition Bureau, “Product of Canada” has a much higher bar to clear. The agency’s threshold for false claims says a product must have had any final processing done in Canada and 98 per cent of its direct production costs incurred in Canada to bear the label. “Made in Canada” products, meanwhile, must have final processing done in Canada and 51 per cent of direct costs traced back domestically.

Individual industries may have built their own certification systems and labels that mark a product as either being fully Canadian, processed in Canada, or being made from Canadian ingredients. Some industries, like locally produced wool and wool products, battle with lack of Canadian processing capacity, making a fully Canadian value chain difficult.

Scott also noted this trend towards base ingredients.

“We annually export $100 billion, mostly unprocessed, semi-processed commodities,” she said. “We import $60 billion of finished product.”

Educating on Canadian product claims

For Scott, the solution for maple-washing starts with clearer understanding and better use of Canada’s existing label rules.

Scott relies heavily on the “Product of Canada” claim. “This is what you want to look at, ‘Product of Canada.’ That’s what you want,” she said.

According to the CFIA, “Product of Canada” means the food’s processing and labour are Canadian, and a “significant amount of the ingredients are Canadian.”

The CFIA further says that a “100 per cent Canadian” claim means all ingredients, labour and processing are Canadian.

“Made in Canada,” though, is the most misunderstood statement in the food industry, Scott said.

“It seems obvious. ‘Made in Canada.’ But what? What was made in Canada?”

“Made in Canada” only means the last substantial transformation occurred here, according to the CFIA. For example, imported ingredients processed into pizza would qualify.

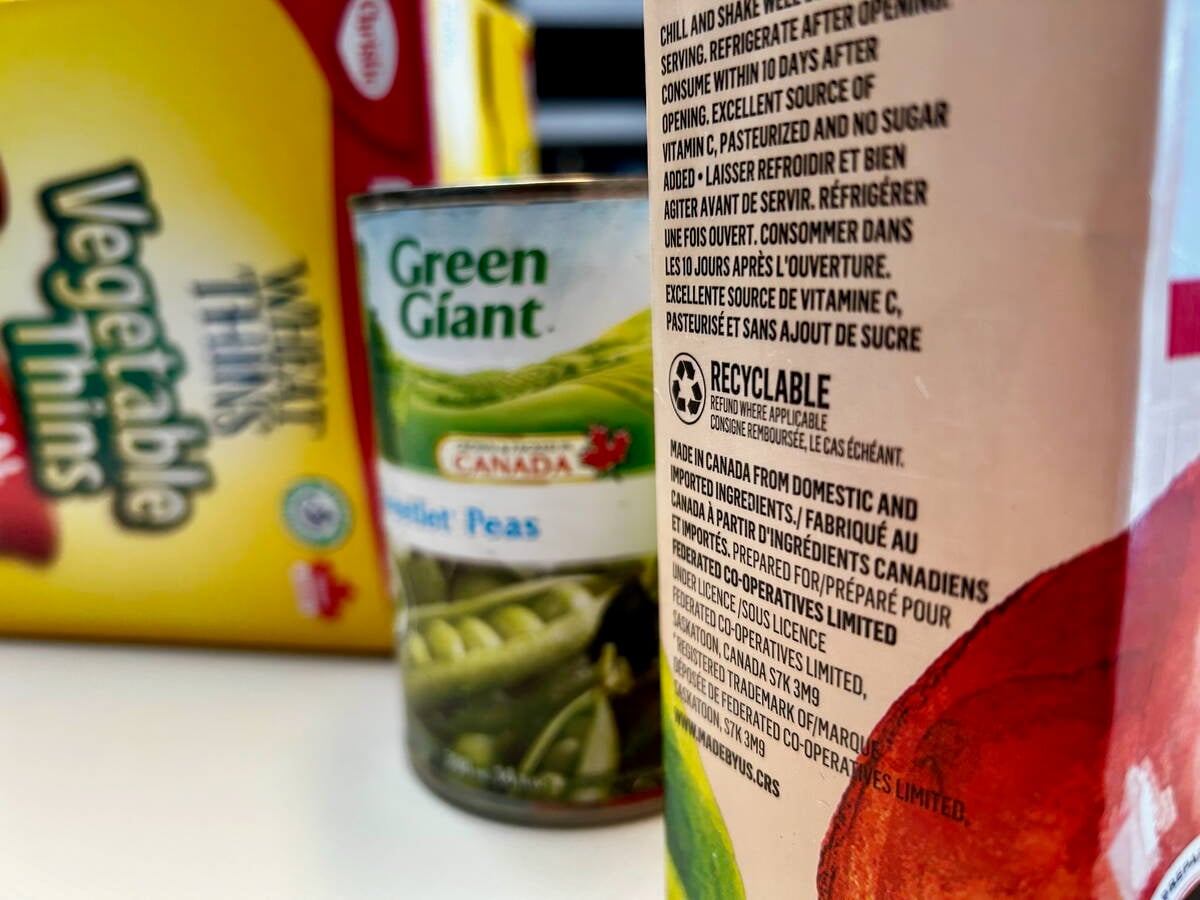

The agency also states the label must include a qualifying statement, such as “Made in Canada from domestic and imported ingredients,” “Made in Canada from imported ingredients,” or “Made in Canada from 100 per cent Canadian (ingredient) and imported ingredients.”

Scott pointed to examples like Quaker Oats, which carry a “100 per cent Canadian oats” statement.”

She also pointed to other label terms matching the CFIA’s guidance, including “Roasted in Canada,” “Processed in Canada,” “Packaged in Canada,” and “Prepared in Canada.”

These claims usually describe where the value-added activity occurred, but not where the ingredients come from, the CFIA says.

Scott warned specifically about the phrase “Prepared for.”

“‘Prepared for’ seems to be used … to describe foods that were prepared for a company or a retailer in Canada,” she said.

The CFIA confirms this designation does not mean the food was prepared in Canada.

Making sense of maple-washing

While travelling abroad, Scott said she realized she didn’t fully understand her own country’s food system. When she returned home, she tried eating only Canadian foods, only to discover that the labelling system made that nearly impossible.

Scott made thousands of cold calls to companies to gather information. Many were shocked that anyone cared.

“Nobody supports selling Canadian to Canadian,” she said companies told her. “Nobody thinks about us.”

Thus inspired, Scott went on to create a new website: canadiancoolfoods.com. It currently lists 450 companies and 4,800 products, along with insights, sourcing information, and links to processors, foragers, fisheries, farms and food producers from coast to coast.

Call to action

It’s up to farmers and consumers to protect and grow the agri-food industry, not governments and grocery stores, Scott believes.

“It’s in your power about what you decide you want to buy,” she said. “Please support our agri-food companies and share the website with everybody.”

The CFIA also encourages Canadians to report misleading labels directly through its website.