The recent prioritization of the Port of Churchill by the federal and Manitoba governments has captured the imagination of Canada’s agriculture sector and other exporters seeking alternative routes to more diverse markets.

The two governments are kicking in a total of $262.5 million, with the feds putting in $180 million and the balance coming from the province.

It’s going to take more than a bit of buzz and a flood of government money to get private sector investors to crack open their wallets and invest in what the federal government has dubbed “Port of Churchill Plus” though — it’s going to require answering a number of burning questions.

Read Also

Trade uncertainty is back on the Canadian national menu

Even if CUSMA-compliant goods remain exempt from Trump’s new tariffs for now, trade risk for farmers has not disappeared, Sylvain Charlebois warns.

WHY IT MATTERS: Agricultural proponents of the Port of Churchill are excited by government support, but that doesn’t guarantee success.

Can it be operated year-round as a northern trade port as Prime Minister Mark Carney has enthused? How much volume can the adjoining Hudson’s Bay Railroad (HBR) accommodate? What can be done to minimize the plight of wildlife and the environment in general, particularly with plans to ship oil?

These questions and others were posed by Barry Prentice, a supply chain management professor with the University of Manitoba’s IH Jasper School of Business, at a recent “In Conversation” luncheon hosted by the McMaster Institute for Transportation and Logistics on Nov. 19.

Prentice offered an overview of some of the bright spots and challenges facing the Port of Churchill Plus.

Breaking the ice

Pivotal to the federal government’s ambitions for its five-year, $180 million railway and port upgrade investments is the question of whether Churchill can realistically serve year-round.

Even with the rapid decline of ice in the Hudson Strait, year-round service would still necessitate extensive use of costly ice-breaking labour and equipment.

Prentice pointed to the province’s $750,000 feasibility study to that end. He also referred to the interest of Montreal-based Fednav, a company billing itself as Canada’s biggest bulk shipper, in operating in the port year-round.

Building back reputation

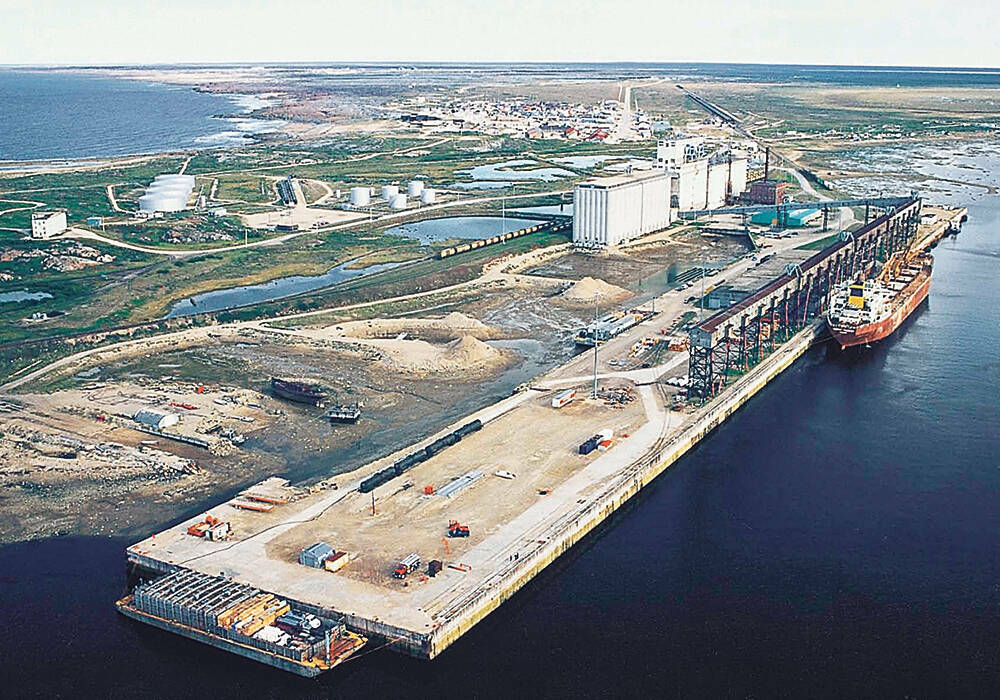

In spite of their status as “the Prairies’ east coast,” the Port of Churchill/Hudson Bay corridor suffers from a “reputational deficit,” said Prentice.

“What do people think about Churchill when they hear about it? Only seasonal navigation comes up. Obviously it is cold, and although this is changing, (there’s a) somewhat wonky rail line that’s had its troubles over time.

“And then finally, a lonely grain elevator that hasn’t seen grain moving very much for some years now. So those are the kinds of ideas that people generally have.”

Climate opportunity

Today, the port and its route to the Atlantic is teeming with trade possibilities, but not for any reason a climate scientist would champion: the retreat of ice that, up until recently, assured Churchill could never be a world-class trade route.

For illustration, Prentice displayed photos comparing ice coverage around 30 years ago to today. The 1993 images showed that even in June the ice extending all the way to Newfoundland with very little open water to be found.

“Moving forward to Jan. 12, 2025, we see open water on the east coast of the Hudson Bay and, of course, pretty much open water up to the Hudson Strait.”

“What we’re seeing is an extension of the season.”

Regional growth

One measure of Churchill’s potential is the sheer number of people living in the Prairie provinces today compared to nearly a century ago. The 1931 national census (the year the port opened) said two million people lived on the Prairies, compared to 8.3 million today, according to the latest Statistics Canada numbers. And that means more demand.

“I expect to see growth continuing, maybe at the same pace,” said Prentice.

Not only is there more demand today, but there are more commodities to ship as well. The port was opened with the sole intent of shipping wheat, but now there’s a long list of goods the corridor could accommodate and some for which it is doing so already. There’s potash, lumber, minerals, petroleum products, sulfur, other grains and containerized freight.

“Containers would be interesting because this is the one product that would move in both directions,” Prentice said.

“… even if 10 per cent of the potash went through Churchill, that commodity alone would be enough to sustain the rail line.”

Barry Prentice

UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA

However, that doesn’t mean the Arctic Gateway Group, the owners and operators of the Port of Churchill, is losing sight of its origins in agriculture. In a recent presentation to Keystone Agriculture Producers (KAP), president and CEO Chris Avery said agricultural commodities are the port’s “core backbone.”

The diversification of the port’s shipping interests has been a welcome change for some.

In a Feb. 23, 2024, Manitoba Co-operator story, Churchill Mayor Michael Spence hailed the return of grain to the port, which had dropped substantially after the demise of the Canadian Wheat Board. But he also wanted the port to be less reliant on a single commodity than it was in the past.

“We are a port community, and one of the commodities that we all know has been historically shipped through the Port of Churchill is grain, but we will diversify; we will look at other products as well,” said Spence.

Environmental impact

A major concern of critics is the movement of oil along the route, which they say presents a threat to both marine and land-dwelling animals, not to mention the Indigenous residents. These and other environmental concerns must be addressed, said Prentice.

The community has a growing tourist trade, interested in paddling in Hudson’s Bay with beluga whales, or coming to view polar bears. They’ll naturally be concerned about the prospect of moving commodities like oil through the shipping route, Prentice said.

Faster shipping potential

The current route for potash from Saskatchewan to Brazil is long and convoluted, said Prentice. The Port of Churchill could change that.

“It’s taken west over the Rocky Mountains, down the coast of North America, through the Panama Canal, around South America and finally, to Brazil.

“Most of South America lies east of North America. So by the time you get through a downhill run to Churchill on the rail and load up, (when) you’re coming out of Churchill you’re almost straight south going to Brazil, so it’s a much shorter route and in theory should be much less expensive.”

Another factor is the amount of cargo required to maintain a railway today, said Prentice.

“For the length of the Hudson’s Bay Railway, it turned out you need about two million tonnes a year of traffic. Well, this railway has seldom seen more than half a million tonnes a year.

“But in the case of potash, we’re already shipping out 20 million tonnes. So even if 10 per cent of the potash went through Churchill, that commodity alone would be enough to sustain the rail line.”

At Avery’s KAP presentation, he stressed the need to increase the HBR’s car-carrying potential in anticipation of heavier traffic in terms of increased use and car weight.

“We need this upgrade to allow rail cars that carry a gross weight of 286,000 pounds per car. Our line allows cars that are weighted 268,000 pounds per car,” Avery said.

— With files from Don Norman