More lambs in a litter means more animals to sell, but it’s not always a good thing when it comes to animal health, warns Dr. Joyce Van Donkersgoed, an Alberta veterinarian and sheep researcher.

“I would say it’s a fallacy to say more is better,” she said at the Saskatchewan Sheep Development Board Symposium held earlier this year.

Van Donkersgoed’s data shows that lower lamb bodyweight at birth becomes a trend throughout the animal’s life and that there was also a higher rate of stillborn lambs and those dying during their first two days in larger litters.

Read Also

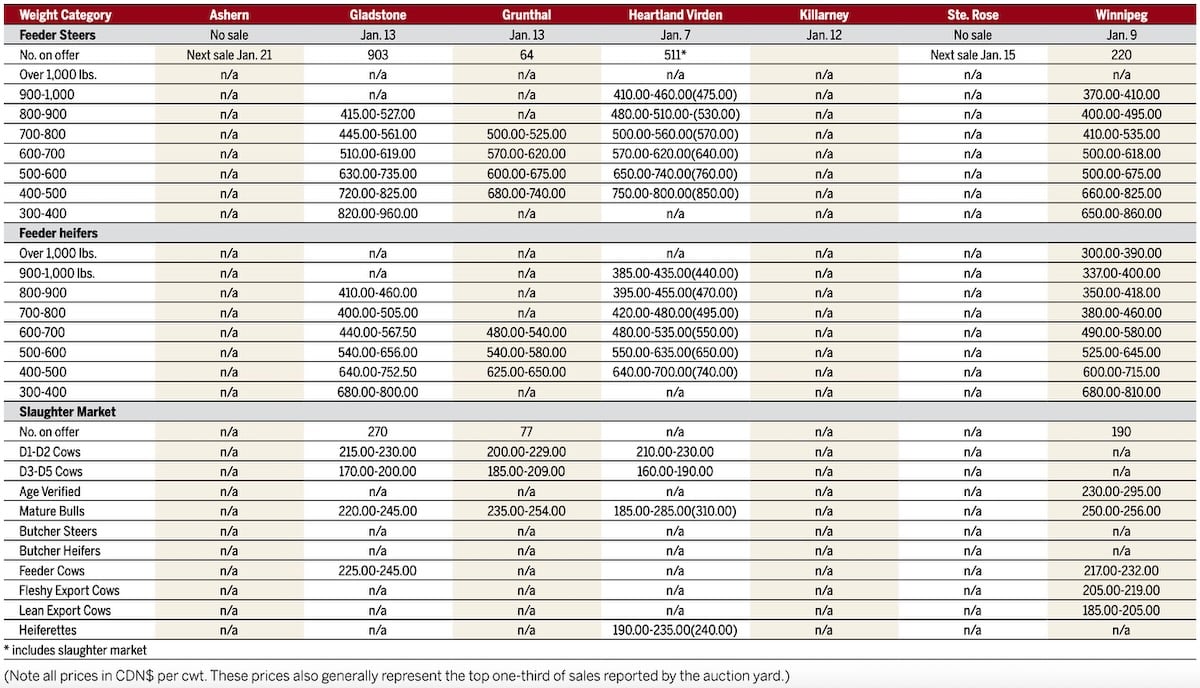

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 15

“So, to me, in my simplistic thinking, is, I think our goal, whether this is cattle or sheep or pigs, is we want that mother, in this case, the ewe, to be able to lamb by herself, unassisted, without intervention. And we want her to raise her own babies, her own lambs, to wean. And then we want those lambs, of course, to be healthy throughout their production life.”

In one study, she observed how difficult it was for a ewe to raise three or more lambs by itself. The mother couldn’t provide enough milk or colostrum.

To try and reduce starvation, Van Donkersgoed’s team would move one to three lambs from a large litter into a separate nursery with milking machines.

However, the problem with a nursery and the milk machines was that the larger lambs would push the smaller ones out of the way — the little guys stayed little, while their larger brethren grew. The starvation rate for quintuplet litters was six per cent, double the three per cent seen with single lambs.

The shared milk machine and close quarters were also a high spreader of disease.

“Number one cause of death, actually, was diarrhea [symptom of enteritis] during the first eight weeks of age, then starvation and then pneumonia.”

Most lamb deaths occurred in the first two to three weeks of age, with starvation occurring during weeks one to two and enteritis during weeks two to three.

Pneumonia had two “spikes”: one early on during the first two to three weeks and then again just before weaning.

The other area of high mortality was the rate of stillbirths in lambs of large litter sizes.

There were no stillbirths with single born lambs, but as the litter size increased to five, the rate increased to 50 per cent. The rate was the same in deaths that occurred before two days old.

The deaths before two days can often be attributed to birthweight, Van Donkersgoed said. The average birthweight for a single lamb was 5.2 kilograms, but 3.2 kg in the larger litter sizes. At weaning, this translated into a four kg difference, with singles weighing in, on average, at nearly 18 kg while quintuplets averaged 14 kg.

“So, you can see that birthweight has an influence all the way to weaning weights,” she said.

“The numbers are different between [the] two groups.… They are statistically different because the difference is not due to chance alone. So, this weight of 17.8 kg in a single is significantly different than twins as well as triplets as well as quadruplets and quintuplets.”

Wean weight is determined by birthweight and average daily gain (ADG), which is usually where some of the difference can be made up.

However, Van Donkersgoed said that isn’t the case with large litters. ADG varied from 0.26 kg per day down to 0.22 in lambs from large litters.

“So, as litter size goes up, death goes up. As litter size goes up, birth [weight] and performance goes down, as I showed you with the numbers before. Then we also saw lower birthweight lambs were higher in overall mortality and death from enteritis, starvation and treatment for pneumonia.”

It was also that lambs with lower weaning weights had a higher overall death risk and were at higher risk of death from pneumonia.

In a second study, to better understand mortality risk during pneumonia, ewes with larger litter sizes were culled from the study. This significantly changed mortality outcomes.

“We also changed another factor,” she said.

“Before, when we had ewes with large litter sizes, we would just pull off, cull the smallest lambs and put them in the nursery. Now what we did is we left lambs of the same size or close size with the ewe to reduce competition on that ewe for milk, and we put the rest in the nursery.”

During this study, there were some similarities to the first one, such as death rates and causes of death.

Starvation, pneumonia and enteritis remained the top causes of death. The rates of this disease after two days of age were the same across all litter sizes.

When it came to stillbirth rates, the number increased in comparison to the first study, jumping to 68 per cent in large litters. However, death before two days of age dropped to 34 per cent in large litters.

Birthweights and weaning weights were where significant differences were seen. For a single lamb, the average birthweight was 4.6 kg while the larger litters averaged 3.1 kg.

The weaning weight had a lower gap this time, with a single lamb weighing 17 kg and those of larger litters averaging 14.3 kg.

Though the two studies had variances, they both had similar general results.

“So, birthweight follows through, not just to weaning, but that follows through to growing and it also follows through the finishing phase of a final body weight,” Van Donkersgoed said.

“It also affects average daily gain during the growing phase and also average daily gain during the finishing phase.”