Verticillium stripe is a common and troublesome disease for canola growers on the eastern half of the Prairies, particularly in Manitoba, but it isn’t nearly as big a deal in Alberta.

Recent research suggests there may be a simple reason for this geographic variation: soil pH.

Why it matters: Verticillium stripe is a concern for canola growers, one that has no current chemical remedies or genetic tools to combat.

Read Also

Market impacts of canola headlines need digesting

January 2026 has been quite the month for Canadian canola trade, how will it all ripple out in the market?

Researchers at the University of Alberta have learned that Verticillium longisporum, the fungus that causes verticillium stripe in canola, is more potent when the soil is slightly alkaline. Lab testing found that fungal colonies were larger when the pH was between 7.4 and 8.6.

“Along with that, the symptoms of infection in both seedlings and adult plants generally became more pronounced as soil pH increased, with disease severity at its worst at pH 7.8,” says a university news release.

A group of plant pathologists at the institution, including Becky Wang, have published their findings in the academic journal Horticulturae.

Gaining a foothold

Manitoba has the dubious distinction of being ground zero for verticillium stripe in Western Canada. The pathogen was first found in 2014 in a canola field near Winnipeg.

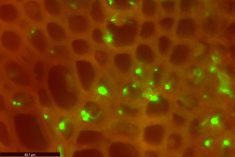

The soil-borne disease infects canola plants and produces tiny, pepper-like sclerotia on or inside the stem. The infection interferes with the uptake of water and nutrients. Symptoms include early ripening, plant stunting and leaf chlorosis and shredding or striping of the stem tissue. Symptoms usually appear later in the growing season.

Over the last decade, the fungal disease has become common in Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan. In 2023, canola disease surveys in Manitoba flagged it as the second most common canola infection in the province, detected in a quarter of surveyed fields, albeit at a low incidence.

The geographic extent of verticillium is unknown, but it continues to spread westward. Travis Wiens, an agronomist in Milestone, Sask., said the disease was detected in North Battleford, Sask., this summer.

Agronomists and canola experts are also unsure about the yield drag of verticillium, but it’s likely a yield robber.

Soil pH

The Alberta researchers grew canola in a lab and experimented with acidic and alkaline soils.

Disease symptoms that peak at a pH of 7.8 “suggests a substantial risk of increased disease severity and yield losses due to verticillium stripe in regions with neutral to slightly alkaline soils,” says the published paper.

Growing canola in a lab is different than field conditions. Even so, the results might explain why Manitoba has also had fewer problems with clubroot, another infamous canola disease.

Clubroot is also soil-borne, causing large galls to form on the roots of canola plants that cause stunting, yellowing and premature ripening.

“In Manitoba, we don’t talk much about clubroot. We talk about verticillium,” said Justine Cornelsen, agronomic and regulatory services manager with BrettYoung Seeds, in December 2023.

Manitoba has more alkaline and neutral pH soil than Alberta and Saskatchewan. Soil in Alberta can be more acidic, which favours the development of clubroot and may hinder the impact of verticillium.

Again, results from a lab don’t always reflect the realities of field conditions. More research may be needed to understand the connection between soil pH and verticillium, the University of Alberta scientists wrote.

“The observation that pH can profoundly affect the growth and virulence of V. longisporum (verticillium) may be valuable for growers,” they said. “Future research, particularly under field conditions, could further enhance our understanding of the pH effects on (verticillium).”