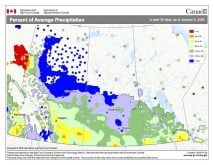

Every year around this time I get a lot of questions asking when we should expect the first snowfall or when I expect that winter will begin. So, while this article was supposed to continue our look at atmospheric oscillations — and in particular, jet streams — I felt we could afford to take a break and look at when we should expect winter to start. Most regions of agricultural Manitoba have already seen their first snowfall, but the warm weather in early November melted most of that away. Then, far-western regions saw some snow, thanks to a strong storm system that walloped Saskatchewan and parts of Alberta. So the question is: When should we usually see the first snow to fall — and when should we “normally” expect winter to arrive?

Read Also

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

As we have been learning over the years, certain weather-related questions sound simple enough, but when you actually look at the question it becomes tougher to figure out. The tough part about trying to figure out when winter starts is how to define just what constitutes the start of winter! Should it be the first significant snowfall? How about when the high temperature consistently stays below 0 C, or should we simply use the astronomical date of Dec. 21, or maybe just stick to the meteorological date of Dec. 1?

False starts

I think most people would agree winter doesn’t really arrive until you have snow on the ground, so for us, I use this as our measure of when winter arrives. Even narrowing it down to this still has some problems. What if, for example, it snows five cm on Oct. 22, then by Nov. 8 it has all melted and we don’t receive any more snow until Dec. 4? Did winter start on Oct. 22 or Dec. 4? For me, I call this situation a false start to winter and I would record the winter in this example as starting on Dec. 4. Once I determined this, I went through the snowfall records for Winnipeg, Brandon and Dauphin and came up with the results you see in the table above.

In the table below we can see that all three regions of agricultural Manitoba have seen winter start in October and as late as mid-December. Winnipeg and Brandon both have an average date for snow to stick around of Nov. 14, with Dauphin being four days earlier at Nov. 10. The “usual range” is a measure of the standard deviation around the average. It indicates the range of dates in which we should expect winter to begin. If winter begins before or after these dates, it is an unusual year.

Single-day snow

Another question I often get is whether we’re going to get a lot of snow this winter — and are we going to see any major snowstorms? Looking back over previous years’ snowfall events in our three different regions, I found that large single-day snowfalls are rare events. When I looked at the number of times Winnipeg, Brandon and Dauphin received more than 10 cm of snow in one day over the last 70 years, I was surprised to find that on average, all three locations have this occur a little less than twice per winter. When we bump up the single-day snowfall to 15 cm or more, this occurs on average a little less than once per winter. If we increase the single-day snowfall to 20 cm or more, the frequency of occurrence drops down to around once every five years. Finally, to show how rare really big snowstorms are in our region, if we take a look at the probability of receiving 30 cm or more in one day, we would find that this kind of event only occurs once every 30 years or so.

One thing I should point out is that from December to February, agricultural Manitoba, on average, receives about 50 cm of snow. So all it takes is one big storm and we will be at average or even above average for the winter. This is why it is so hard to predict whether winters will be wet or dry — often it only takes one storm to make a wet winter!

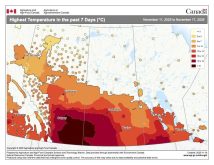

A second question that comes up with the talk of snow is cold temperatures — that is, just when will the cold temperatures move in? The answer to that is almost always tied to when the snow moves in. While we can get some cold temperatures without snow covering the ground, to get extremely cold temperatures, and sustained cold temperatures, we need to have snow cover.

Snow cover acts in a couple of ways to contribute to colder temperatures. First, it insulates the ground, trapping the ground heat and preventing it from warming up the air above it. Secondly, snow has a very high albedo; that is, it reflects a very large proportion of the sun’s energy. So, instead of the sun’s energy being absorbed by the ground and then released to warm the air, it gets reflected and we do not warm up much during the day. Finally, snow, simply put, is cold! We really notice this in the spring, but having snow on the ground at any time of the year acts like a refrigerator to keep temperatures down.

In my next article we will continue our look at atmospheric oscillations, or maybe, depending on what happens, why winter seems to be having a tough time taking hold this year.