I don’t know, maybe everyone is busy shovelling and plowing snow, but I have not received any weather questions for a couple of weeks now. If you do have a question, please email me at [email protected].

Over the last month or so I have noticed the snowdrifts in my yard forming in some unusual places. So my question to me is, what the heck is going on this winter with all the snow and southerly winds?

To understand what is going on this winter, we need to understand where our winter storm systems tend to originate. Nearly all our winter storms form along the edge of the Rocky Mountains. In the weather school articles I go over every couple of years, I have discussed why this is. While I don’t have enough space to go over it now, just know it is connected to what happens as the air flows over the mountains.

Read Also

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

Because of the geographical setup, we can see storm systems, or areas of low pressure, develop from the Yukon in the north all the way down to Colorado and New Mexico in the south. Along this range we tend to see these winter storms develop in three areas. The first area is to our southwest ranging from Montana to New Mexico. These storm systems will often bring our heaviest snows. The farther south they form, the stronger these storm systems tend to be. This is because, for a storm system to develop that far south and move northward and hit our region, there must be a large or strong dip in the jet stream. The strength of curvature of the jet stream helps to aid the strength of the storm. Also, these southern storms can often tap into significant amounts of moisture as they often originate in the Gulf of Mexico. This moisture adds energy to the storm and gives the storm system the ability to drop large amounts of snow.

The second area of storm development is over southern Alberta. These storms, being farther north, often do not have a strong or large curve in the jet stream to add strength, and they are usually cut off from the deep gulf moisture to the south. Instead, their moisture will come in off the Pacific Ocean, which means that these systems are usually drier in nature. These systems can still have large temperature differences to work with as very cold air is almost always in place to the north of these storms.

The final location is in northern Alberta and the Yukon. Like the systems that form in southern Alberta, these systems usually don’t have strong or large curvatures in the jet stream to work with and they are usually even drier than the systems that form to the south. The northern latitude of these systems will also result in less temperature difference, in turn resulting in weaker and drier systems in general.

Taking sides

What does all this have to do with snowfall and wind direction? Try to picture this in your mind as I try to explain. We need to remember how air flows around storm systems. The general airflow around an area of low pressure is counter-clockwise — east to southerly winds ahead of the low, and northerly to westerly behind the low. Secondly, we need to remember where precipitation tends to form around a low. Typical lows have the precipitation form on the east to northeast section of the low with the precipitation wrapping around to the north to northwest side.

With this in mind, picture a storm system coming up from the south or southwest. Since these storms approach from the south and then slide by to the east, we tend to stay on the north side of the low. This places us in the main precipitation area along with being in the region of north or northwesterly winds. This results in nearly all the precipitation falling with north or northwest winds.

Lows that originate in southern Alberta track from west to east. This means for our region the exact track of the low can make a big difference in precipitation and winds. Precipitation on the eastern side of the low will move in first and then areas on the southern side of the low will often see a break in the precipitation, whereas areas to the north will see precipitation continue. Winds will start off east or southeast, then become south as the low tracks by. Finally, as the low pulls off to the east the winds switch to the north or northwest as the precipitation comes to an end. This means with these lows most of the precipitation is accompanied by south winds with only a short period of precipitation accompanied by north or northwest winds. Areas to the north of the low will see a longer period of precipitation with a quicker switch to northerly winds.

Lastly, we have the lows that form to our northwest. These lows track southeastward and rarely move directly over southern or even central Manitoba. This means our region almost always stays on the southern side of the low. We will see an area of precipitation move in as the low approaches and this will be accompanied by southerly winds. This precipitation usually ends fairly quickly, with the chance of more light precipitation moving in on the back side along with northerly winds as the low tracks off to the east.

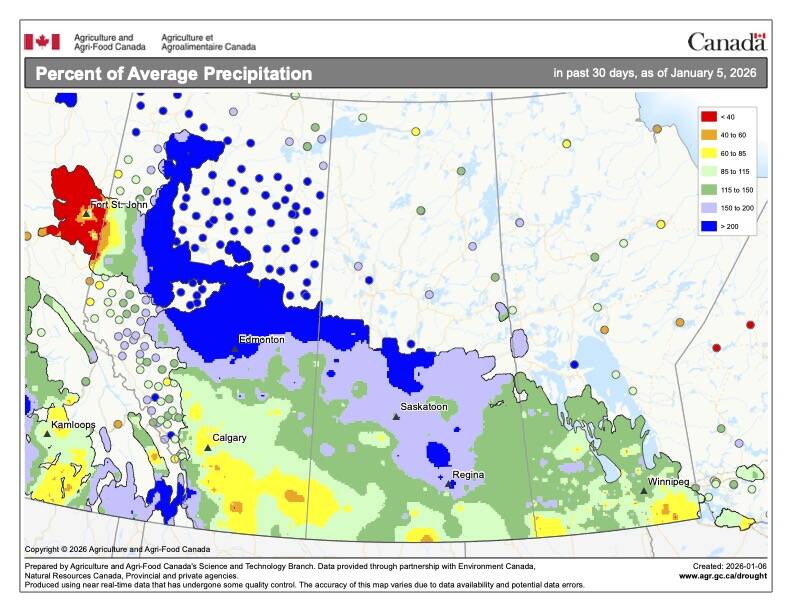

What can we conclude about the origins of the winter storms or low-pressure systems so far this winter? For the most part they have come from either southern Alberta or northern Alberta/Yukon. While it is not unusual to see these types of lows, what is a little unusual is just how many we have seen in a row. The current pattern across North America is favourable for these types of lows to continue forming, and until we see a switch in this pattern, we can probably expect to see more snow accompanied by south winds.