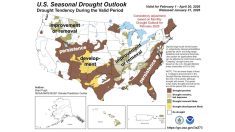

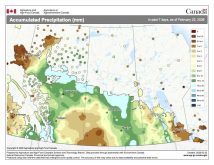

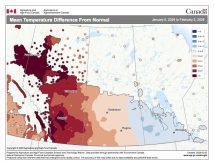

I originally thought for this week I would do an article about just how much snow different parts of the Prairies have received so far this winter, which would then lead us into our first look at spring flooding, but I think that will have to wait just a bit longer for a couple of reasons. Firstly, with more snow still expected across our region at the time of writing, it would be better to wait and see what impact that may have on totals. Secondly, I received a couple of emails asking me to explain in more detail how wind is generated in our atmosphere. I guess that means it’s time to go back to weather school and take a deep dive into just what creates the winds we experience.

Read Also

Forecasting spring 2026 weather on the Prairies

What weather can farmers expect across Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan as they head into seeding? Plus: a lesson on what makes the seasons turn

So, just what the heck is wind and, more importantly, what causes it to blow? When we talk about winds there are three main categories we can use to classify them. The first of these are primary winds, which result from the general circulation of the atmosphere. Our westerly winds are an example of this. The second category of wind is secondary winds. These are the winds associated with the movement of high- and low-pressure systems. It is these winds that tend to bring us most of our day-to-day winds. The final category of wind is the tertiary winds which include such local winds as the chinooks and land and sea (or large lake) breezes. Thinking about these categories of winds kind of reminds me of the naming of vines when growing giant pumpkins, but I digress.

OK, now that we know that there are three general categories of winds, the question still remains: What actually causes the wind to blow? As with most things in our atmosphere there is a simple answer that explains the basics, but when you get right down to it, even the reason for wind blowing can get fairly complex. In this week’s article we will keep things basic and simply go into the four main controlling factors of the wind. In the followup articles we will dig deeper.

Before we do that let us first take a short pause and actually define what we mean by wind. After looking up literally a dozen different definitions of wind, the one that I thought was best was probably the simplest: wind is the horizontal movement of air across the Earth’s surface, with turbulence occasionally causing a vertical component to this movement. When hearing it put this way, I think we all basically knew that — but this still does not tell us why the wind blows. So, on to the main driving forces behind wind.

Contents under pressure

The most important force that helps drive our winds is actually one of the weakest forces in nature: gravity. If we didn’t have any gravity on Earth, the atmosphere wouldn’t have any weight. Without weight, the atmosphere would not compress itself and there would be no increasing density as you get closer to the Earth’s surface. This would mean that without gravity there would be no atmospheric pressure.

If you want to discount gravity and simply say it is a given and it shouldn’t be taken into account, then atmospheric pressure would be the top force driving the wind. In all actuality, it is the difference in atmospheric pressure that creates the wind, or what we call the pressure gradient force. It’s this pressure gradient force that drives our wind.

The best way to think about this is to picture two large pails. One pail is full of water while the other is empty. If we were to connect the bottom of the two pails with a hose and allow water to flow freely between the two pails, the water from the full pail would flow into the empty pail. Why? Because there is a pressure difference, or pressure gradient, between the two pails. The bigger the pressure difference, the faster the water will flow. This same analogy holds true for our atmosphere: the bigger the atmospheric pressure difference between one area and another, the faster the air will move between them. The faster the air flows, the greater the wind speed. These areas of higher and lower air pressure are called — you guessed it — highs and lows! Pretty basic, right?

Well, that pretty much describes why we have winds, so why are there two other forces involved? Well, as we dig deeper into what drives wind, we will discover that the Coriolis force complicates things, by deflecting winds as they travel across the globe. Remember, I pointed out there is a basic and a complex understanding of wind; now we are getting into the complex area.

Finally, there is the sneaky force called friction: the subtle force that slowly drains away energy from any and all moving systems. Even within the weather there is no getting away from this sinister force. OK, maybe I’m being a little too melodramatic — after all, without the force of friction, we wouldn’t be able to shelter ourselves from the wind, winds’ speeds would get insanely fast and the weather as we know it would simply not be the same.

Unfortunately, that is all the room I have for this issue. Next issue we will continue our deep dive into wind and hopefully after that, the snow machine will have come to an end and I can finally tally up all the numbers and see just where we stand as we head into March and April — which, by the way, just happen to be one of the snowiest parts of the year!