Time to continue our series of articles on different types of severe summer weather. I like to re-examine these topics every year or two due to the importance of understanding the different types of severe weather, and also because most people find this aspect of weather so fascinating. In this issue we are going to look at what is probably the most feared and costly summer severe weather event: hail.

If you have spent any significant amount of time living on the Prairies, there is a good chance you have probably experienced a hailstorm. While hail can occur pretty much anywhere across North America, there are two main regions where the chances of experiencing a hailstorm are significantly higher. The first region is the central U.S. and the second region is the Canadian Prairies — in particular, Alberta.

Read Also

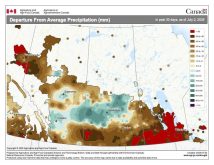

June brings drought relief to western Prairies

Farmers on the Canadian Prairies saw more rain in June than they did earlier in the 2025 growing season

For those of you who routinely read my column, then you know I have a fair number of weather peeves. Well, I have another one and, you guessed it, it has to do with hail, or rather, the improper use of the term hail. Hail refers to the falling of ice from a cumulonimbus (thunderstorm) cloud. Ice pellets, snow pellets and graupel (a snowflake that has been coated in ice) are not hail and should not be called hail. These types of precipitation will often occur in the spring or late fall and are not associated with thunderstorms. You need to have a thunderstorm for hail to occur.

One of the first questions I get asked about hail is: can it be too warm for hail? The answer: yes. If the upper atmosphere is warm, then the freezing level in the atmosphere is very high up. If a thunderstorm does develop, and if hail forms in the storm, chances are that the hail will melt well before it ever reaches the ground. So, the key ingredient for hail to form is to have plenty of cold air aloft and to make sure that it is not too high up off the ground. This is one of the reasons why Alberta, and the higher elevations of the U.S. Midwest, experience more than their share of hail. The higher elevation often means the freezing layer is lower to the ground, thus there’s a greater chance that hail will not melt before making it to the ground.

Most thunderstorms will produce hail; the question is whether the hail will grow large enough to make it to the ground without completely melting. As we have already discussed, a very low freezing level helps this happen, because the hailstone only has a short distance to fall through the relatively warm air. Another way to keep a hailstone from melting before it hits the ground is to start off with a really big hailstone! This is one of the main reasons Alberta sees so much hail compared to everyone else in Canada. The topography of Alberta is such that while ground temperatures can be really warm, the freezing layer is not that high up relative to what it might be in Manitoba.

Now, here is where a second common misconception about thunderstorms and hail lies. To get really big hailstones you do not necessarily need a really tall (or high) thunderstorm.

Hail forms when a particle passes from the warm (liquid) part of the cloud into the cold (freezing) part of the cloud. When this occurs, any water on the particle freezes and you now have a small hailstone. Now, if that hailstone just kept going up toward the top of the thunderstorm it wouldn’t accumulate much more ice and therefore it would remain small. For hailstones to get really big they must go back into the warm (liquid) section of the storm, pick up more water, then go back up into the cold section of the cloud so the water can freeze. Repeat this cycle a number of times and you can get some really big hailstones. Picture a popcorn machine, or better yet, an old-fashioned bingo machine. The balls, or hailstones, are continually moving up and down due to the strong updraft.

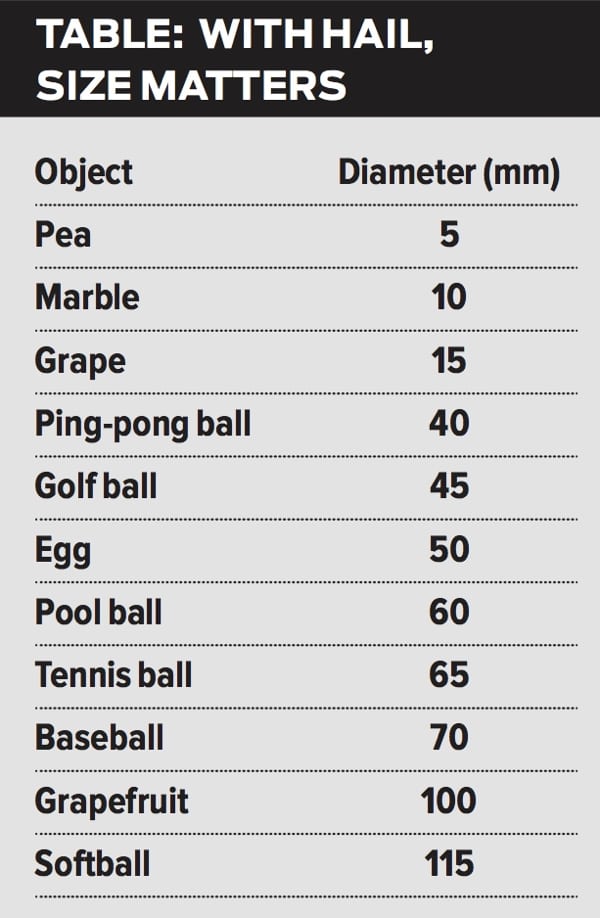

When it comes to hail, size really does matter! Pea-sized hail will do little if any damage to structures or plants, while golf ball-sized hailstones can literally destroy everything in their path. When it comes to measuring hailstone size, things become a little strange. That is, you don’t usually hear that the hail will be around 50 mm in diameter. Instead, you hear that the hail was the size of a golf ball or an egg. Of all the things we measure in regards to weather, hail has by far the most descriptive measurements. The table shows some of the more common descriptive terms used for hail, and the approximate size those hailstones would be.

So far during this summer’s severe weather season I haven’t seen or heard about any significant or large hailstorms. Let’s hope that continues for the rest of the summer.

In the next article we’ll examine how this summer has been shaping up compared to previous years. We’ll also wrap up our severe summer weather series with a look at what is often the most damaging event: straight-line winds.