So far this month weather conditions have been fairly good for thunderstorms to develop with plenty of warm, humid air around. This week, we’ll continue our look at severe thunderstorms, and specifically, the most deadly part — tornadoes.

What are tornadoes and how do they form? A classic definition of a tornado is a violently rotating column of air that extends from a thunderstorm to the ground, which may or may not be visible as a funnel cloud. For this rotating column of air to be classified as a tornado it must touch the ground.

Read Also

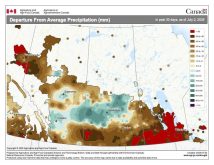

June brings drought relief to western Prairies

Farmers on the Canadian Prairies saw more rain in June than they did earlier in the 2025 growing season

As to how tornadoes form, the real answer is, we just don’t know. Tornadoes usually develop from supercell thunderstorms, but these are difficult to predict. Even if we were able to accurately predict where and when these thunderstorms would develop, the intense part of the thunderstorm usually only covers an area of a few hundred square kilometres. Within this area the really severe weather may only occur in a small section of maybe 10 to 20 square kilometres. Now, if we look at the size of a tornado, we would find that they range from as small as about 40 metres to as large as two km across, with the average width being around 100-200 metres. This means that, as far as weather phenomena are concerned, tornadoes are very small, which makes them difficult to study first hand.

Funnel clouds

Before I go on to look at tornadoes in more detail, let’s first take a look at one of the weakest members of the tornado family, the funnel cloud, and in particular, something called a cold air funnel. The fundamentals behind the development of these funnel clouds is similar to how tornadoes get started and will serve as a good starting point for our look at tornadoes.

All tornadoes develop out of a funnel cloud. In strong thunderstorms, these funnels elongate and may eventually touch the ground to become a tornado, but a funnel cloud all by itself is not considered a tornado. While a fair bit of research has been done on tornadoes and the storms that produce them, very little research has been done on cold air funnels, therefore, we know very little about them. In general, cold air funnels form in environments where we would not typically expect severe weather to develop, that is, in hot, muggy, unstable air. Usually cold air funnels will form when there is a large pool of cold air aloft that is most often associated with an upper-level low. These conditions provide two critical ingredients that are believed to be necessary for the development of cold air funnels — instability and vorticity.

If you think back to what you know about instability in the atmosphere, you should remember that warm air will rise and cold air will sink. If the atmosphere is unstable you need either really warm air at the surface or very cold air in the upper atmosphere. This is why there needs to be a pool of cold air aloft for cold air funnels to form, because this provides the first ingredient — instability, or rising air.

Like a figure skater

The second ingredient is vorticity. This simply means spinning air. Areas of low pressure are large areas of spinning air, too large to form into a funnel cloud or tornado. But within this large area of spinning air smaller regions get “spun up,” creating what meteorologists call a vorticity-rich environment — containing lots of little eddies of spinning air. What scientists believe happens is that one of these small eddies of spinning air gets caught in an updraft. This updraft then pulls on and elongates the eddy, causing it to contract in width, and just like a figure skater pulling their arms in during a spin, this causes the rotation to gain momentum, creating a funnel cloud.

These funnel clouds are generally very weak and short lived, and will rarely become strong enough or last long enough to touch down. If they do touch down, they can then be referred to as tornadoes, but even then they rarely cause much damage, often comparable to that of a very strong dust devil. In fact, when these cold air funnels do touch down they are sometimes referred to as land spouts.

Since the potential exists for cold air funnels to touch down as a tornado, Environment Canada has to issue special weather statements to warn the public about them. Since they rarely touch down, and even when they do they rarely cause damage, such statements will usually urge the public to watch for these to occur and to take precautions if necessary, i.e. you don’t have to go diving for the nearest storm shelter if you do see one of them forming.

We’ll continue our discussion on more severe tornadoes and straight-line winds in the next issue.