It was no small feat achieving the kind of Trans-Pacific Partnership deal that offers export agricultural commodity groups the kind of market access they were seeking with modest, but significant, concessions on supply management.

If the early reports are to be believed (details were announced just before press time), Canada’s trade negotiators deserve kudos for maintaining Canada’s balanced approach in the face of relentless and somewhat lopsided pressure from countries seeking greater access to Canada’s domestic dairy, poultry and egg markets.

However, this isn’t the end of the discussion around the future of supply management on the domestic front. Although the increased market access may seem small, the federal government has already acknowledged through a $4.3-billion compensation package that it will have an effect on producer incomes.

Read Also

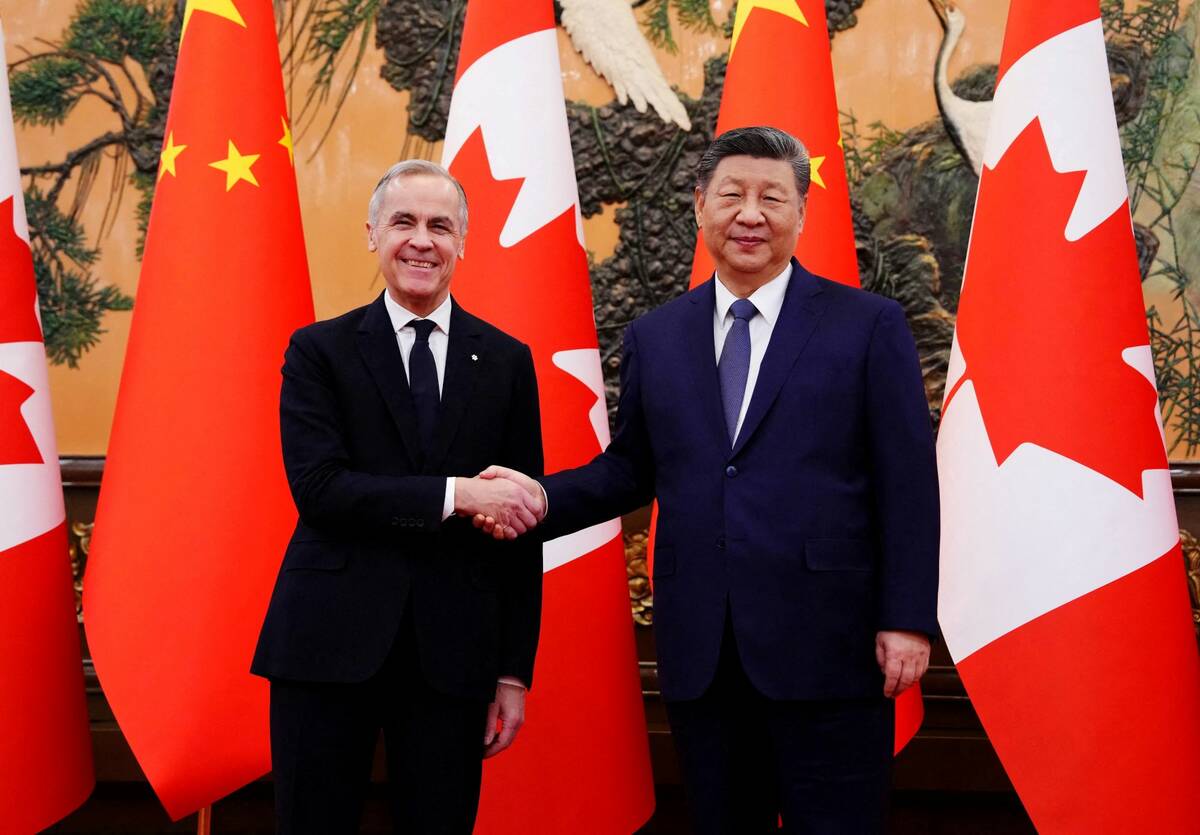

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

And as noted in a recent discussion paper put forward by the Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute (CAPI), that sector must address a growing trade deficit as imports of products such as milk proteins flow into the country continue to rise, while dairy farmers remain restricted as to how much they can export. This industry must continue to evolve.

As for the rest of the agri-food sector — the grains, oilseeds, beef and pork sectors — it is worth noting that gaining market access isn’t the same as securing market share. What has been gained is an opportunity to compete on an equal tariff footing. Whether Canada can lock in those sales will depend on price and quality.

Given the transportation logistics, competing on price for Asian markets seems like a long shot. That leaves quality as our best option.

On that front, CAPI is asking a provocative question of Canada’s agri-food sector: Can this country become home to the world’s most trusted food system?

It’s provocative because those few words capture the essence of a host of questions that have been swirling around the farming and food sector lately. There is much at stake in how they are answered.

It also implies a shift in thinking, policy and structure if indeed the industry chooses to throw itself behind a vision that recognizes the role of trust in differentiating Canadian-grown and processed in markets at home and abroad.

CAPI, which is a national, non-government, independent agri-food policy institute, has teamed up with the think-tank Canada 2020 to suggest that this country is at a crossroads. The TPP only underscores that reality.

While commodity agriculture was the source of its prosperity in the past, “business as usual may provide incremental growth or it may be insufficient to meet our growth expectations,” according to the paper, which can be found online at capi-icpa.ca.

This country’s primary processing sector is a global player in only a handful of segments, such as canola oil. The secondary processing sector, which is Canada’s largest manufacturing segment, is facing rising trade deficits — just like dairy.

CAPI says global agriculture is facing a transition. In the future, success will depend heavily on environmental sustainability.

“Many other countries will have no choice but to cap or curtail some unsustainable agricultural practices. Canada has the capacity to produce more while still removing carbon from the atmosphere, improving water quality and enhancing the well-being of its people. We have to decide how to use this opportunity,” it says.

As such, a Canada brand based on being the most trusted must be more than a slogan saying “trust me.”

“Trust will dictate the standard for food quality in the future — and we need to declare our place on this measurement.”

CAPI says that while Canada’s record isn’t spotless, it has comparative advantages that speak to changing consumer expectations, such as fewer chemical residues, good soil, ample water and sound governance.

The challenge will be harnessing those advantages, and benchmarking in a manner customers being asked to pay a premium know precisely what they are paying to get.

It means that as a sector, Canadian agriculture must set aside some of the petty defensiveness that bubbles to the surface as soon as questions of trust and social licence are raised.

“We need to reflect on the comparative advantages of the future, and how we will act on them, so we can respond to these realities,” he said. “Taking action will require being highly collaborative and better aligned.”

“Capitalizing on our advantages will also take new ideas, skilled people, investment, data, science, technology, infrastructure and the right regulations,” it says.

CAPI and 2020 are hosting a forum on this issue Nov. 3 and 4 in Ottawa. If you can’t attend, you can still participate in the discussion online.

For more information on the forum next month, watch this video interview with CAPI President David McInnes.

Video produced by Bruce Sargent, FarmBoy Productions