My key story of 2020 began with a small, embattled quarry project north of Winnipeg and ended up illustrating, in microcosm, what local governments might expect if proposed provincial law goes forward.

Residents of the RM of Rosser contacted me about a quarry proposed to be built in their backyard. I met them in a house a few hundred yards from the site, and they told me a story that stretched back over a decade.

The property owner at the time had tried to build a quarry. The residents protested. They were afraid the quarry would contaminate their water, choke them with dust, deafen them and blast errant rocks at their houses.

Read Also

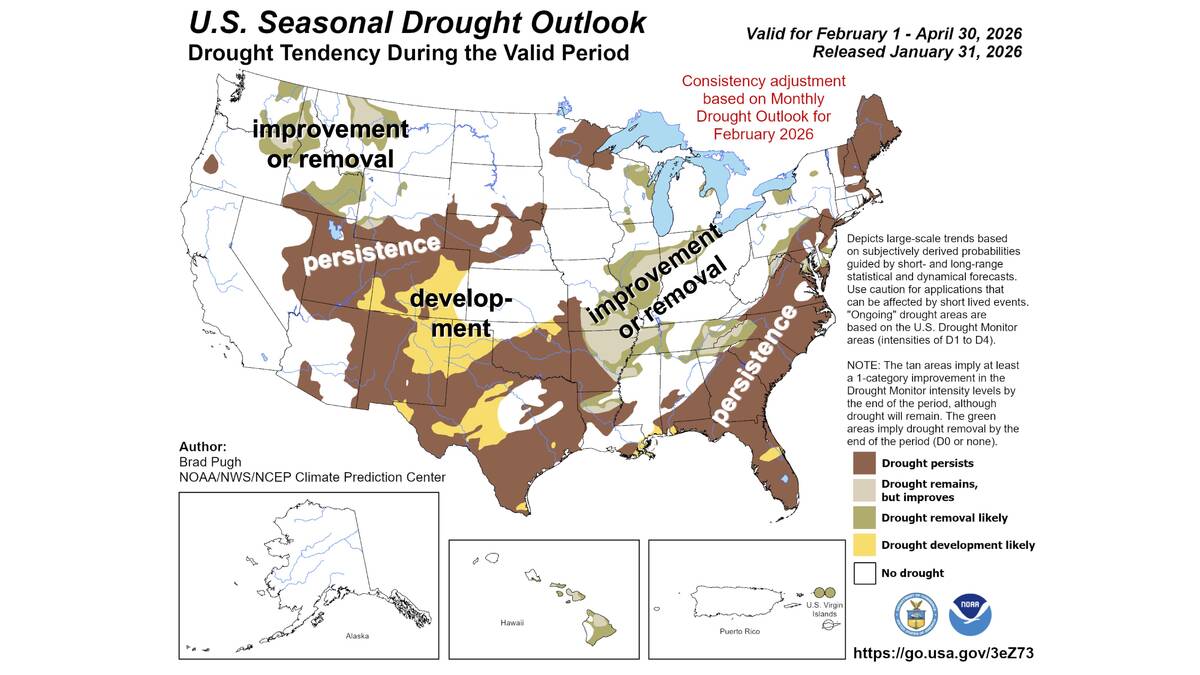

Neutral conditions drive 2026 weather as La Niña subsides

U.S. government meteorologist expects there will be neutral ENSO conditions for the 2026 farm growing season.

The municipality shot the project down. The land changed hands. Rinse and repeat for several more years.

Current landowner Colleen Munro took the RM to court in 2017, but the court upheld Rosser’s decision. Then the law changed.

In 2018, Bill 19 amended the Planning Act to allow owners of aggregate quarries and large-scale livestock operations to appeal to the Municipal Board (a provincial, quasi-judicial tribunal) if their conditional use applications were denied.

When it came before the board in July, Munro’s case against Rosser was the first test of the new amendment. However, the province had already proposed a bill to expand those rights of appeal even further.

Then known as Bill 48, it was reintroduced in this latest session of the legislature as Bill 37.

Undermining democracy?

Two factors hang in the balance. On one hand, you have the need for a streamlined planning and development process and an arm’s-length arbiter if that process breaks down. On the other, there’s local government autonomy.

At the Association of Manitoba Municipalities (AMM) AGM this November, Municipal Relations Minister Rochelle Squires said permitting delays and a broken planning system were costing Manitoba millions (citing a 2019 study from the provincial Treasury Board Secretariat).

“We know of projects that have been stalled for years (not days), as well as projects that have never come,” the report said.

Councils in small communities might also be accused of bias due to personal relationships, or of being overly swayed by activists, said Paul Thomas, professor emeritus of political studies at the University of Manitoba.

Whereas, at least in theory, the Municipal Board is staffed by civil servants and other unelected officials with no political axe to grind.

However, it also takes the final word on these decisions away from those who were elected to make them.

On November 23, AMM passed two resolutions to lobby for changes to Bill 37, including for the removal of the new rights of appeal from the bill.

The appearance of bias

On September 18, the Municipal Board ruled in favour of Munro. It allowed the quarry to be built under a stringent list of conditions, which Munro and the RM had pre-arranged. These conditions went a long way toward addressing the many concerns residents raised.

“I believe the province has done what needs to be done,” Munro told the Co-operator. For her, this marked the end of five years of legal battles over the site.

However, residents who’d opposed the project swiftly cried foul.

“We were afraid going in that the hearing was biased, and nothing that happened there changed our minds,” said Brynn Kaplen.

Residents had told me they feared the board wouldn’t be objective because some members had ties to the provincial Conservatives. For instance, Rick Borotsik, a member who presided over hearings, is a former PC MLA.

Provincial Liberal party leader, Dougald Lamont, who said he had attended the first day of hearings at the request of residents, said the decision set a “disturbing precedent.”

He claimed Munro and several members of the board were PC party donors (confirmed through election records). “It just seems to me that if people want to get their way, they just have to give lots of money to the PC party,” he said.

A statement from the province did not address allegations of bias toward PC donors.

Building a quarry seems to align with the province’s agenda.

A provincial explainer on Bill 19 said, “A significant factor in the cost of aggregate is the distance in which the material is hauled… it is of key importance in ensuring the availability of high-quality aggregate in areas where population growth is resulting in increasing demand.”

The Lilyfield Quarry sits not far from the burgeoning CentrePort industrial development.

“It doesn’t mean that everything will be done according to the government’s wishes,” Thomas said. “But you think about what the provincial government stands for. It stands for deregulation… it’s pro-development.”

Emphasis on evidence

The Lilyfield decision was the first of its kind, so the Municipal Board had to decide how it would decide as well as what.

The board opted for a fresh hearing. It evaluated all the evidence and made a new decision instead of ruling if the RM was reasonable in denying the permit.

The judgment showed the board would approach these appeals as fresh hearings where new evidence could be given, said Gerard Kennedy, professor of administrative law at the University of Manitoba.

“You have to say, ‘point to the evidence as to why something should or should not be developed,’ and not rely on, ‘we just don’t like the development,’” he said.

Munro’s team laid out thorough evidence on why the proposed quarry wouldn’t damage the water supply, create too much dust or noise, or (in a key point of contention) cause dangerous levels of traffic on local roads.

The RM of Rosser said it paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to hire its own researchers and they could not refute this evidence.

Residents testified that the quarry would disrupt their quiet neighbourhood, scare their animals and potentially wreck their home-based businesses. This subjective evidence counts for something, but not a lot, said Kennedy.

To argue social or economic damage, best to bring in experts and quantify the issue as much as possible, he said.

Some observers feared this emphasis on evidence would be a double-edged sword.

Developers know they can get a return on their investment and are prepared to spend a lot of money up front to prove their case, said Thomas. Rural municipalities don’t always have the same war chest to pay for research.

“I think (developers are) well heeled and well connected,” said Thomas. “That gives them an advantage sometimes.”

Bill 37 awaits its second reading and committee hearings. Squires told AMM delegates she expected this would happen in spring. The province modified the bill slightly from its earlier iteration (Bill 48), but didn’t touch the sections on the right to appeal.