It’s no secret that climate and weather play a significant role in agriculture. It’s been that way since the first seed was planted. A drought or a flood would pose massive risks to farmers. Accurate forecasting is invaluable in mitigating the effects of weather anomalies. For centuries farmers turned to the latest oracle who claimed to be able to forecast what the seasons would bring.

Today, those forecasts are firmly rooted in science and hard data, using the latest technologies and, unsurprisingly, are much more useful than they have ever been. Trevor Hadwen, an agri-climate specialist who works for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the National Agroclimate Information Service (NAIS), spoke during the Ag in Motion Discovery Plus Virtual Farm Show in July. He gave an overview of the tools and techniques he and his department use to parse the data they collect, and how that information ultimately helps in decision-making at the farm level and at the government policy level.

Read Also

Calling all farmers: What do you want us to ask at the Ag in Motion farm show?

Ag in Motion is back July 15-17, 2025; we want to know the production questions you need our reporters to ask

More climate information, provided by these sorts of tools, could help producers manage the variable weather events on their farm.

Hadwen began by pointing out the importance of monitoring the impacts of climate in the rain-fed agricultural environment of Western Canada. “Producers frequently are forced to deal with extreme weather of some sort during the growing season,” said Hadwen. “Drought, intense heat, high-intensity rainfall, flooding, saturated fields, hail, frost and extreme wind events are all common. These extreme events have significant impact on individual producers and the agricultural industry as a whole,” he said.

It is because of this high-risk, highly variable environment, that NAIS is mandated to monitor climate risks and to provide information to the agriculture sector. This information helps the agricultural industry to adapt and the government to focus their programs and policies in a way that mitigates the risks to producers.

Gathering the data to achieve this goal comes from a variety of sources that fall into four different areas:

Climate stations: These stations are located throughout the country and provide measured details of parameters such as rainfall and temperature.

Climate models: These models combine climate station data with other types of data to provide a more realistic look at conditions.

Satellite data: Data provided from satellites can provide a very good coverage of data over a large area and start to look at the impacts of weather and climate for a region.

People networks: Polling producers and industry partners to find out about the impacts they’re facing from local weather and conditions.

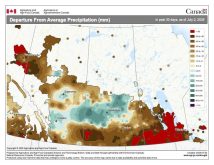

AAFC’s Drought Watch page (a sub-page of the AAFC’s weather and climate page) outlines many of the products available to producers. A link on that page will take users to its Agroclimate maps. These maps are produced on national and regional scales and various time frames as well as various weather parameters and are the result of climate station measurements and agricultural models. They are a big part of the mandate of NAIS. “We produce hundreds of these maps each day,” said Hadwen.

The Canadian Drought Monitor (CDM) is another link from the same page. The CDM is produced monthly throughout the growing season to show conditions across Canada. “The maps that are created are supported on the website by a narrative discussing how the drought situation evolved as well as various statistics,” explains Hadwen.

On the horizon for NAIS is the Canadian Vegetation Drought Response Index (VegDRI). The model is currently being developed and tested for release in 2021. Originally developed at the University of Nebraska, and currently being used in the U.S., it is a hybrid drought index that combines satellite observations of vegetation health with climate station data and physical information about the land surface. “This dataset will allow users to better see the impacts of dry and wet weather on crops and other vegetation, with the potential for both improved impact assessment for financial programs and improved ecosystem impact assessments,” explained Hadwen.

But even with all this data at their disposal, the full impact of weather and climate on agriculture can’t be done without feet on the ground and that’s where the “people networks” come in. AAFC’s Agroclimate Impact Reporter (AIR) is a survey-based tool that lets producers provide information directly to the AAFC on how weather and climate have impacted their farm or their region each month during the growing season. AIR is a five-minute survey intended to help inform the department’s understanding of local issues producers are facing. “The AIR activity goes beyond drought and looks for other possible impacts including excess moisture, flooding, frost, livestock health and crop quality issues,” said Hadwen.

So, how does all this help? Hadwen said that the information collected is instrumental for innovation in policy and programs that in turn, help the producer. He points to the example of the AAFC’s Livestock Tax Deferral Provision (LTDP) that allows farmers who sell part of their breeding herd due to drought or flooding in designated regions to defer a portion of sale proceeds to the following year. The analytics that Hadwen’s department provide, allow the government to identify the regions affected. “The LTD Provision helps producers dealing with drought and excess moisture by removing the burden of paying taxes on the sale of livestock during excessively wet or dry years,” he said.