A strip of newly planted trees and shrubs on the east side of the recreation centre in Morden might look merely like landscaping. Wait until it starts to rain.

Then it’s an example of how towns and cities can also help overland flooding and nutrient run-off.

The site at the east side of the Morden Access Event Centre is the city’s first official rain garden, installed this spring in a partnership with the Pembina Valley Conservation District.

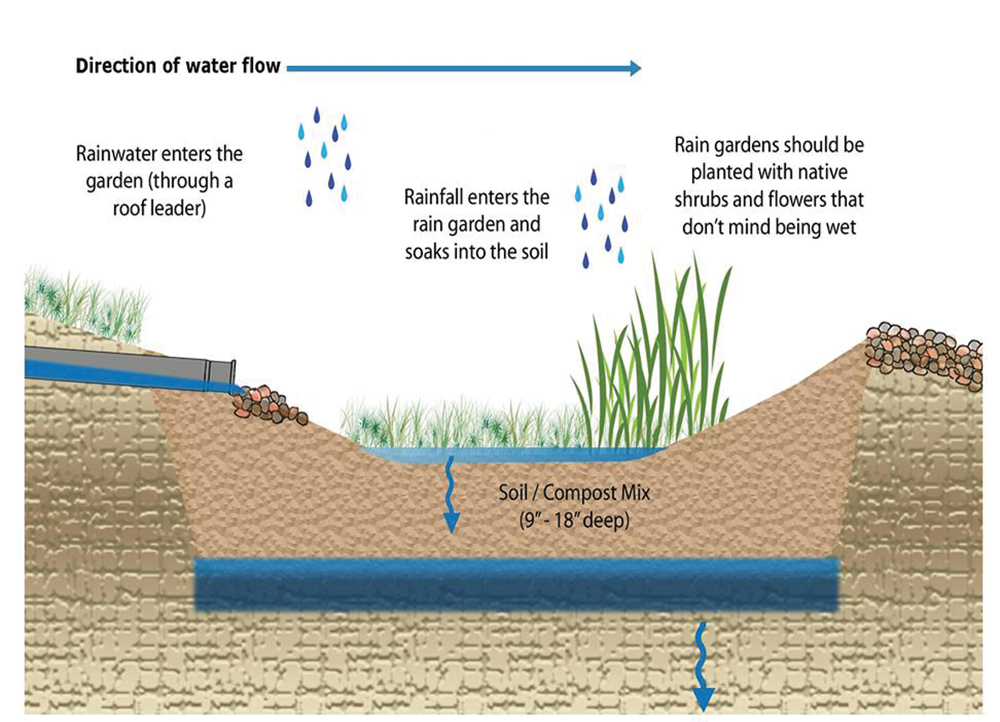

A rain garden is a perennial planted area specially designed to harvest or capture and use rainwater that otherwise runs off and can contribute to local flooding. At the end of Morden’s rain garden is a 2,500-gallon (11,365-litre) tank to serve as a gigantic rain barrel.

Read Also

June brings drought relief to western Prairies

Farmers on the Canadian Prairies saw more rain in June than they did earlier in the 2025 growing season

Over a season of summer rains, city officials have calculated it will collect roughly 27,000 litres of rainwater, to be used by public works to water all the flowers and other trees and shrubbery around Morden.

That’s water that doesn’t need to come from the tap, said Cliff Greenfield, PVCD manager.

“This is captured rainwater they’ll be using, instead of expensive high-quality potable water,” he said.

The other benefits of the rain garden include groundwater recharge, improving water quality and increasing biodiversity and carbon storage. It looks far better than a barren arena wall and parking lot.

They’re one more way we can begin to drought-proof our communities, says Greenfield, adding it’s hoped the project will inspire homeowners and business owners too.

Wider adoption of rain capture and rain garden projects also means urban areas are contributing to water-management solutions rather than to the problem.

No infiltration through concrete

Whether they realize it or not, cities and towns play a role in both run-off and surface water contamination, with their built-up hard-surface areas and general compaction that leave nowhere for rainwater to infiltrate. Instead it’s being sent downstream to overload storm sewers, drainage ditches and streams. That run-off carries its own share of nutrients and sediments, not to mention, oil, gas, and heavy metals.

Adoption of ways to capture and infiltrate water — and use it more wisely — is a way to help prepare for a more sustainable future in drought-prone areas, said Greenfield.

Morden was part of a Pembina Valley-wide initiative three years ago, when the Blue Water of 2012 looked at long-term prospects for water demand and supply in the region.

The three-year study of water use and supply in municipalities in the PVCD concluded that even though residents use significantly less water than the average Manitoban, their frugality alone won’t prevent a regional water shortage by 2040. (Area residents use about 30 per cent less water compared to other Manitobans, or 160 litres of water a day compared to a provincial average of 227 litres and the Canadian average of 339.)

But if the region keeps relying on various lakes and reservoirs, groundwater wells and aquifers and while increasing population, it will run short. And prospects of finding new water sources are remote given the potential for a drier century ahead, the study said.

Morden’s rain garden is one of a series of conservation practices the study recommended, as well as stopping water leakage in homes and industry, introducing efficient appliances and changing public behaviour and practices around water use.

Water conservation also means a longer infrastructure lifespan and lower costs of providing water.

In 2010 the Public Utilities Board mandated municipalities to charge a fee on their utility bills for wear and tear on infrastructure, and earmark the cash in a reserve fund for future repairs.

A practice like a rain garden would have made perfect sense to a previous generation whose use of a cistern to capture water was commonplace, say other PVCD officials.

“Our grandparents understood the value of water and trying to use what resources they had to the utmost and best use. That’s why they had cisterns to capture rainwater,” PVCD chairman and Darlingford-area farmer Murray Seymour said in a news release.

“This rain capture and rain garden project is something we are already doing in rural areas with small- to medium-size dams that hold water back and reduce downstream flooding, and improve water quality downstream as well,” he added.

Morden’s rain garden is not unique, and elsewhere in Manitoba municipalities offer rain garden programs with rebates to those constructing them.

These kinds of demonstration projects are a way conservation districts can work with urbanites to involve them in water management too, Greenfield said.