Two different summer weather events are regularly overlooked but potentially severe: rainfall and humidity.

Humidity, by its simplest definition, is the amount of water vapour in the air. The warmer the air, the greater the distance between air molecules and therefore the greater the holding capacity of air for water vapour. Warm air has the capacity to hold much more water than cold air.

The most common way humidity is reported is relative humidity, which is probably one of the most misunderstood terms used to describe weather. Relative humidity is a ratio of the amount of water vapour in the air compared to the maximum that it could hold under those same conditions, and is expressed as a percentage.

Read Also

What is perfect Christmas weather?

What is ‘perfect’ Christmas weather on the Prairies? Here’s where you should head this holiday, according to historical weather data.

For example, if we had air temperature of 10 C and eight grams of water vapour per kilogram of air, our relative humidity would be 100 per cent, since air at 10 C can hold eight grams of water vapour. If this same air was warmed to 30 C and the amount of water vapour in the air didn’t change, the relative humidity would be around 29 per cent, because air at 30 C can hold 28 grams of water vapour.

This is where the misunderstanding develops. When the air temperature was 10 C and the relative humidity was 100 per cent, people would say it is humid out, but once the temperature warmed to 30 C and the relative humidity dropped to 29 per cent, people would say it is very dry out. In reality, the amount of water vapour in the air has not changed, only the temperature.

A better way to measure humidity is by using the dew point temperature or dew point. This measurement is a fairly simple way of telling us exactly how much moisture is in the air no matter how the temperature changes during the day.

The dew point is the temperature at which air is cool enough for condensation (or dew) to form. In other words, it is the air temperature that would give us 100 per cent relative humidity.

For example, if it is 18 C outside early in the morning and the dew point is 18 C, the relative humidity would be 100 per cent. By afternoon, as the air warms, the dew point would still be around 18 C if no additional water vapour was added or removed, but the relative humidity would drop.

The best way to determine humidity is as follows:

- At dew points less than 10 C, the atmosphere is fairly dry.

- Dew points in the 10-15 C range are comfortable.

- Dew points in the 15-20 C range are humid, starting to feel uncomfortable.

- Dew points over 20 C are very humid, start to feel very uncomfortable.

- Dew points over 25 C are extremely humid and conditions will be very uncomfortable and even dangerous.

Let’s go back to relative humidity again, to pound home the difference between this and the dew point.

If the dew point is 25 C, it is very humid no matter what the temperature. If the temperature is 35 C, the relative humidity would only be around 55 per cent, and I could guarantee that at least one person would say it’s not that humid. So remember, if it’s a hot summer day with dew points in the low 20s, even if the relative humidity is only 50 per cent, it is still humid out.

Now let’s consider severe summer weather that we tend not to think about until it creeps up — heavy or extreme rainfall. The impact of heavy rain and resultant flooding far outweighs most of the other severe summer weather events.

What is a heavy or extreme rainfall event? According to Environment Canada, rainfall warnings are issued according to the following criteria. If it is going to be a short duration event, such as a thunderstorm, expect upwards of 50 millimetres of rain in one hour before a rainfall warning will be issued, at least across the Prairies.

It is lower over the east and west coasts. While this might not make sense at first, if you think about it, those areas rarely get the intense thunderstorms seen in the inland areas of Canada.

If the rainfall event is expected to be a longer-term event, the criterion for a warning is when 50 mm of rain is expected within 24 hours or 75 mm within 48 hours. Sometimes, due to the nature of summer storms, you can have both types of warnings at the same time.

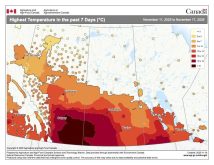

There has been plenty of talk connecting extreme rainfall events and global warming. I won’t get into arguments about global warming. You know my views on it. Our planet is getting warmer whether you want to believe it or not. It is not just the air temperature that is getting warmer but also the oceans.

Combine warmer oceans with warmer air and you get an increase in atmospheric moisture levels, or humidity. This does not mean we will always see higher humidity, but rather, it means the atmosphere as a whole can hold more water vapour and is also receiving more water vapour.

All this water vapour must go somewhere and will eventually fall in some form of precipitation. The more water vapour available, the greater the chance that the precipitation will be an extreme event.

In the next and final instalment of our annual look at severe summer weather, we will continue to explore extreme rainfall events and the factors that contribute to them.