I received a few requests over the last week to stop discussing heavy rainfall and thunderstorms and start talking about summer heat waves. All of this, of course, is in the hope that talking about heat will maybe somehow make it happen. Oh, if only it was that simple. I also received a few questions simply asking me, ‘What the heck is going on?’ and, ‘What is with all the rain and cold temperatures?’

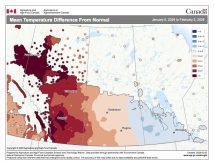

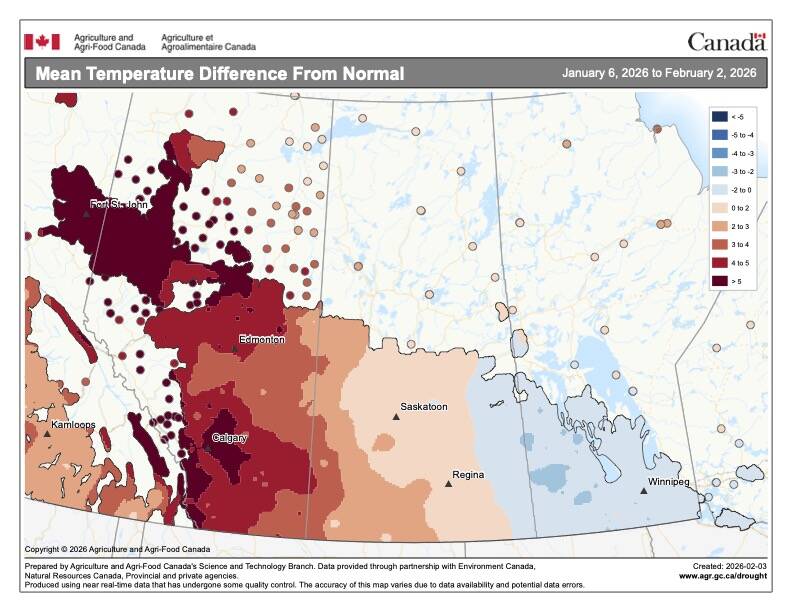

Well, it might be hard to believe, but last month the planet recorded its fifth-warmest April on record. There was only one major region on Earth that showed below-average temperatures, and you guessed it — it was across a large part of central North America. Lucky us!

Read Also

Prairie weather all starts with the sun

The sun’s radiation comes to us in many forms, some of which are harmful to organic life while others are completely harmless or even essential, Daniel Bezte writes.

What the heck is going on? You may recall discussions we have had in the past on the general setup of weather patterns on Earth. The equator is always warm, and the poles are always cold. Sure, the poles warm a little bit each summer, especially the north polar region due to the fact that it is an ocean, but compared to the equator it is cold. Now, this cold air over the poles does not always just sit nicely right on top of the poles, but it drifts around nudged in different directions depending on what is happening in the mid-latitudes. This year it just so happens that conditions around the globe resulted in some large ridges of high pressure building across Russia, which brought warm temperatures to that region but also helped to deflect some of the cold air usually over this region. The cold air had to go somewhere else, and, as it turns out, it ended up over us.

This southward displacement of arctic air is also what is helping to fuel the storm systems and resulting rains we have been seeing for over a month now. Just like with thunderstorms, areas of low pressure feed off temperature differences; the bigger the difference, the stronger the low can be. Add in the fact that the current setup across North American is allowing for a lot of Gulf of Mexico moisture to move northward, and the stage is set for rain, and lots of it.

OK, so that’s the ‘why’; the billion-dollar question is, ‘When will this pattern break down?’ Because to be honest, time is running out for farmers in some regions of Manitoba. Well, if you have already read the forecast then you know this wet pattern does not look like it is totally done with us yet. If you have not read the forecast, then maybe don’t. It does look like we should be transitioning into a warmer pattern, but the weather models are still hinting at keeping us wet. One positive view is that often when the weather pattern switches, the weather models can really struggle as they try to hang on to the current pattern. I will keep my fingers crossed that we are seeing the beginning of a pattern switch.

Compression

Now, on to severe summer weather and heat waves. To get those truly hot, long-lasting summer heat waves we need a ridge of high pressure to develop and then park or get stuck over our region. The ridge of high pressure allows for a couple of things to happen. First, the descending air in the area of high pressure inhibits the growth of clouds; this in turn means plenty of sunshine, and in the summer, sunshine means heat. On their own, sunny skies do not mean a heat wave; we see plenty of sunny days in a row without experiencing a heat wave.

The next part has to do with the strength of the high. When the high is strong, we get very strong subsidence or sinking of air. As this air is pushed downward, it hits the ground and is compressed. Now, anyone who has used an air compressor, or even just a hand pump, knows that as you compress air you are forcing the air particles closer together, which in turn increases the rate of particle collisions, and these collisions transfer energy which we feel as heat. Don’t believe me? Grab a bike pump, give it 20 or so pumps and then feel the bottom of the pump — it’s hot, due to the compression of air.

So, when there is a strong ridge of high pressure over us, the compression of sinking air can dramatically heat the air and give us some truly warm days. Now, if the upper high is not that warm, then all this compressing and heating of the air won’t do that much to give us record-breaking temperatures. If the upper high is warm to begin with, then this compression of air, combined with the additional heating of the sun, can really push the temperatures up.

That is about all I have room for in this issue. I will re-explore this topic in a little more detail soon. Hopefully, we will see some heat soon, maybe not record breaking — just imagine how it would feel if record-breaking heat moved in with all the water around. But some nice warm weather would really help improve the state of mind for many people.