Long range forecasting is difficult, and even with advances in computer modelling, most forecasts beyond 30 days are usually no more statistically accurate than tossing a coin.

However, general atmospheric circulation patterns can load the weather coin a bit.

This year a neutral to weak La Niña event is developing over the Pacific Ocean. What is La Niña and how might it impact our weather this winter?

Read Also

Winter grazing strategies offer cost relief for Manitoba cattle producer

How cover crops, straw and silage pile grazing fit in a western Manitoba rancher’s winter feeding plan — and how to make sure they meet cattle’s nutritional needs.

Most of us know an El Niño event, an unusual warming of the central and eastern parts of the equatorial Pacific Ocean. This warming changes the general circulation of the atmosphere over the Pacific.

In particular, trade winds weaken and in extreme cases they reverse direction. This can cause big changes in the location of heat and moisture globally and give rise to anomalous temperature and precipitation events around the world.

The recent El Niño helped drive nearly two years of temperature records we just experienced.

La Niña is the opposite. La Niña means the little girl, and can sometimes be called El Viejo, the anti-El Niño, or simply a cold event.

It occurs when strength increases in the normal pattern of trade wind circulation. Under normal conditions, these winds move westward, carrying warm surface water to Indonesia and Australia and allowing cooler water to upwell along the South American coast.

When a La Niña event occurs, these trade winds are stronger, which helps increase the amount of upwelling. This creates more cool water along the coast of South and Central America and builds up warmer water on the western side of the Pacific Ocean.

On the western side of the Pacific, the influx of warmer water causes an increase in cloud over southeast Asia and results in wetter than normal conditions for that region during the Northern Hemisphere winter.

What does this have to do with our weather in Western Canada? Changes in the tropical Pacific are usually accompanied by large changes in the jet stream across the mid-latitudes (our part of the world), shifting the usual location of the jet stream across North America.

This can contribute to large changes in the normal location and strength of storm paths and can cause temperature and precipitation anomalies over North America that can persist formonths. These changes are most strongly felt in the winter.

According to the latest La Niña advisory, nearly all models predict it will continue through early 2025. The different models disagree over the eventual strength of this La Niña event, but recent data suggests it will be weak and short-lived.

This would likely result in limited impact on our weather this winter, so confidence in the long-range forecast is low. Let’s look at what has happened during previous La Niña winters.

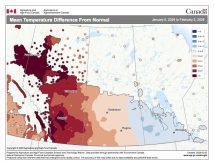

Sometimes it easier to show the impact of different weather events with a map. The first map shows the typical impact on our weather during a La Niña winter across Canada and the U.S. Typically we see colder than average temperatures, as indicated in the long-range computer forecasts. In our recent winter weather outlook, the computer models almost all predicted a warm start to the winter, followed by colder than average conditions in the second half.

The map shows a strong La Niña, but it looks like we will only see a weak one this winter. In the last dozen weak La Niñas, six brought near- to below-average temperatures, five were near- to above-average, and one saw above-average temperatures over the eastern prairies and below-average temperatures over western regions.

Statistically, this does not help much in predicting this winter’s temperature forecast.

What about snowfall? This snow map shows the difference from average snowfall across Canada and the U.S. during the previous nine weak La Niñas. You can see that during a weak La Niña winter we will, on average, see above-average snowfall over most of Alberta and parts of extreme southern Saskatchewan, along with the north-central parts of Saskatchewan.

The rest of south-central Saskatchewan and southern and central Manitoba typically see below-average snowfall. What grabs my attention is the band of above-average snowfall to our south. It wouldn’t take much of a northward nudge to put the southern prairies into above-average snowfall.

It will be interesting to watch how this winter plays out.