A life of spreadsheets might not be for everyone, but accountancy is important work. It’s how we measure success, track expenses, and how we hold people and organizations accountable.

A new report from one of Canada’s major accounting firms, Deloitte Canada, proposes a different application for accounting principles, one that farmers may not be accustomed to using.

Despite its awkward title, “Growing a Net Zero Food System: An open-source framework for climate-smart agri-food products in Canada,” it tackles an important concept.

Read Also

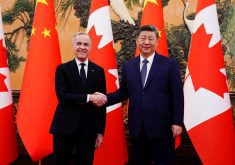

Trade uncertainty is back on the Canadian national menu

Even if CUSMA-compliant goods remain exempt from Trump’s new tariffs for now, trade risk for farmers has not disappeared, Sylvain Charlebois warns.

Essentially the authors say there’s a patchwork of approaches used by different organizations that aim to reduce carbon emissions in agriculture. Some are earnest efforts, some are outright greenwashing and most are too confusing and conflicting to ensure a coherent approach to a big issue.

It’s hard to discern exactly what’s being accounted for or how and why. The net result could be that emissions grow rather than shrink in coming years, according to the authors.

A lot of farmers might look at that and ask “why bother?” But like it or not, the carbon footprint of agricultural products is going to be under the microscope, and the best, simplest and cheapest way to meet this goal will become increasingly important.

A farmer might not think this is an important issue, but if processors, retailers and consumers do, that farmer will have to meet the standard, regardless of their own feelings.

A partner in the report is the Canadian Alliance for Net-Zero Agri-food (CANZA). This organization describes itself as a “… national alliance to foster collaboration and innovation to drive Canada’s agri-food system towards net-zero.”

A look at its members reveals it was founded by food firms McCain and Maple Leaf, the nation’s largest grocer Loblaw Companies and RBC, one of Canada’s largest lenders. With this kind of corporate heft backing the concept, it’s unlikely to fade away.

The folks at Deloitte suggest an “open-source framework” that could be readily adopted by any sector of the food system. It would be robust and transparent, and designed so it is not an undue burden for the country’s farmers.

That might seem like a tall order, but it’s a worthy goal. Otherwise, the current patchwork of rules and standards is going to grow ever more complex and become even more unwieldy.

Opting out might be an option for now, but eventually, end users will come to expect standards like these. The net zero agriculture bus is driven by government, but industry players are jumping aboard and seem ready to take the wheel.

Tracking this information is important, but the authors also acknowledge there are issues to overcome. Most of them involve data, which will be key to accounting for reductions in carbon emissions.

First there’s the trust factor. Farmers must trust their value chain partners enough to share the data, and the partners (and consumers) have to be able to trust it is accurate.

Then there are familiar concerns like who owns the data, traceability, cost of implementation and, to quote the report, “ensuring that meeting data needs won’t impose undue burdens on farmers.”

Also included are the concepts of commercialization and incentives for implementing the agricultural practices that will be needed to reduce emissions. The authors laid out criteria for a product certification program, and how it could be activated and governed appropriately.

The report is a starting point for an important conversation. Producer groups should involve themselves in the discussion. What appears to be a reasonable ask from a Toronto boardroom might be a lot more difficult to implement on a farm in rural Manitoba.

Failing to become involved could mean a standard is set without meaningful farmer involvement, and that could be disastrous.