El Niño conditions are developing across the Pacific with an increasing probability that a full-fledged El Niño episode will occur during the second half of 2017.

Pacific equatorial winds have slackened since the start of the year and a characteristic tongue of warm water has begun to form stretching from Peru towards the international dateline.

Both are consistent with the development of El Niño and are likely to strengthen during the second and third quarters.

The U.S. government’s Climate Prediction Center (CPC) last month forecast El Niño conditions would prevail by the end of the Northern Hemisphere summer, but put the probability at only 50 per cent.

Read Also

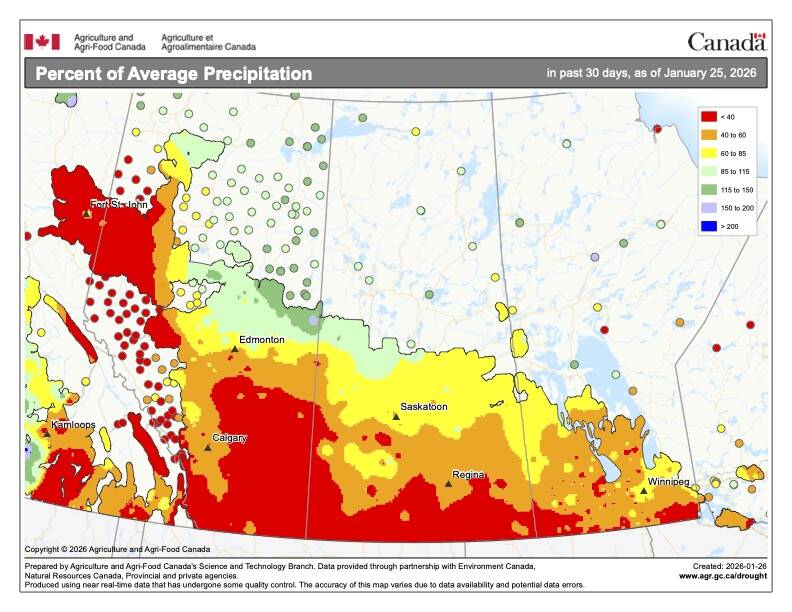

What’s the weather for last half of winter 2025-2026?

A last look at 2025 temperature and precipitation on the Prairies, plus what weather forecasters expect through to spring 2026.

Most El Niño indicators have strengthened since then so the probability is likely to be revised higher when the CPC issues its next forecast later in May.

But the strength of any future El Niño remains highly uncertain as does its impact on temperatures and precipitation across North America this winter.

El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) describe closely linked oceanic and atmospheric processes that stretch across the Pacific and the neighbouring maritime continent of Southeast Asia.

The oceanic component sees cold water well up from the deep ocean off the coast of Peru and move west across the Pacific carried on the surface equatorial current.

There is a return flow of warm water eastwards across the Pacific on countercurrents to the north and south of the equator and also on an equatorial undercurrent deeper in the ocean.

The atmospheric component sees warm, moist air rise over the maritime continent and western Pacific, then flow east through the upper atmosphere towards South America.

The air cools and sinks over the colder waters off South America, before returning towards Asia in a steady westward flow known to mariners as the trade winds.

The oceanic and atmospheric circulations are coupled, with the equatorial winds helping drive the surface equatorial current, and sea surface temperature differentials reinforcing the rising and falling air columns.

But the strength of the circulations and the degree of coupling varies at seasonal, annual and inter-annual scales.

When the circulations are particularly strong and tightly coupled, the equatorial winds accelerate, the equatorial current picks up and colder-than-average water is carried farther from the Peru coast towards the dateline.

When the circulations are weak and uncoupled, the winds slacken, the current slows and warmer-than-normal water extends from Peru to the dateline.

The stronger, cooler phase of this cycle is termed La Niña while the weaker, warmer phase of the cycle is El Niño.

The atmospheric and oceanic circulations that lie at the heart of ENSO involve very large thermal masses of air and water which means they exhibit a lot of short-term persistence.

The short-term stability (especially the thermal stability of the ocean) makes the ENSO cycle somewhat forecastable.

The trickiest time of year to make forecasts is during the first quarter of the year when ENSO effects are weakening and the possibility of a phase transition (from El Niño to La Niña or vice versa) is greatest.

While forecasters have had a fair amount of success in predicting phase shifts in ENSO, forecasting the strength of an El Niño or La Niña episode has proved much harder.

El Niño and La Niña episodes vary enormously in their intensity. The winter of 2015-16 saw an unusually intense El Niño but it was followed by a very weak La Niña episode in 2016-17.

ENSO has a major impact on temperatures and rainfall around the Pacific and Indian basins and a smaller impact on the Atlantic basin.

But the main effects are felt within the tropics, with a much more limited effect on weather outside the tropics in the mid-latitudes.

Researchers have found links between ENSO and temperatures and precipitation in some parts of North America owing to its impact on the position of the Pacific and polar jet streams.

ENSO’s impact on North America tends to be regional rather than national. Higher temperatures in some areas are offset by lower ones in others.

El Niño tends to be associated with a warmer-than-normal winter in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, and a colder and wetter winter in the U.S. Southwest and Southeast.

La Niña tends to bring colder and wetter weather to the Pacific Northwest but dry and warm conditions to the U.S. Southeast and U.S. Southwest.

If El Niño develops later this year it should bring warmer temperatures to Washington state and neighbouring areas but colder, wetter weather to a belt of southern states stretching from California through Texas to Florida.

The exact impact depends critically on the strength of the El Niño phase and its interaction with nearer atmospheric and oceanic circulations, which remain impossible to predict this far out.