It’s often said employees are the bedrock of any business.

Without them wheels don’t turn, work isn’t done, products aren’t created and customers aren’t served.

If that really is so, and there’s a small library of management manuals to back that claim, agriculture in Canada is in real trouble.

A joint study from the Conference Board of Canada and the Canadian Agriculture Human Resource Council (CAHRC) paints a grim picture of the sector, where jobs go begging and are vacant at twice the rate of other economic sectors. The study says the answer is to bring in temporary foreign workers in ever-larger numbers, streamlining the process so farmers don’t have to be bothered with pesky paperwork or justifications and generally just accepting that it won’t be Canadian citizens filling these jobs.

Read Also

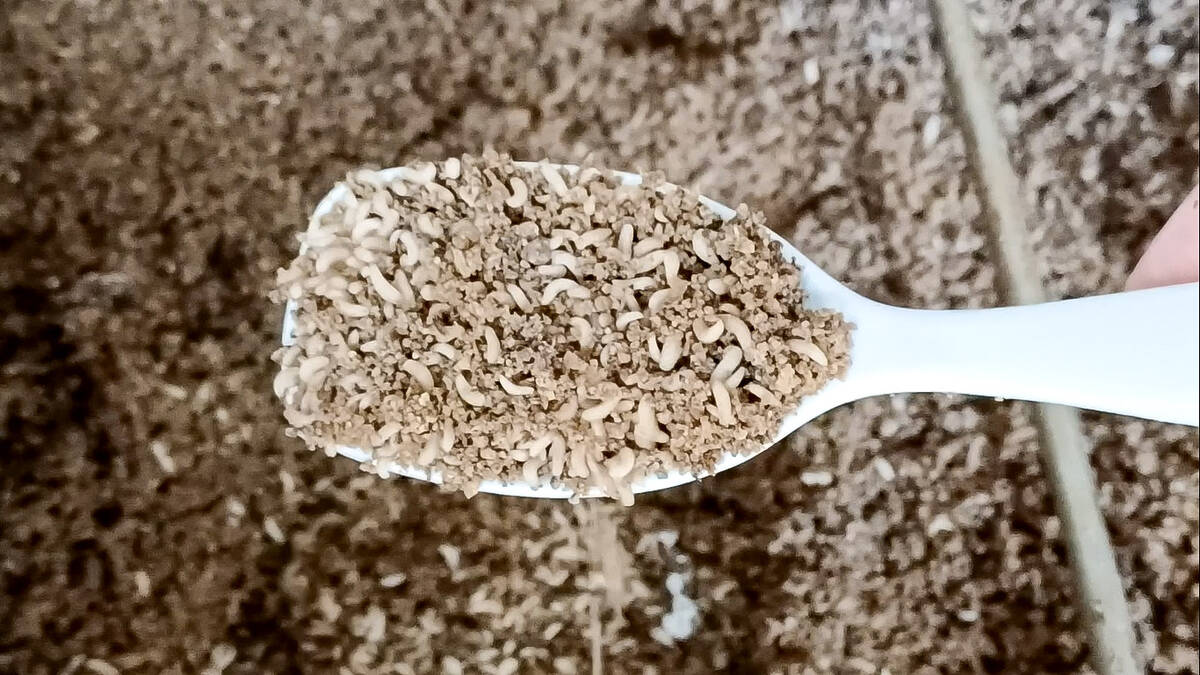

Bug farming has a scaling problem

Why hasn’t bug farming scaled despite huge investment and subsidies? A look at the technical, cost and market realities behind its struggle.

I can certainly understand the attraction of this approach. After all, other sectors have employed it with good effect, and it does seem like it would provide a relatively quick solution. I’m just not sure that in the end it’s a sustainable solution, or one that the industry should be comfortable with the moral implications of.

There are stories all across Canada of TFWs being abused and taken advantage of, treated as virtual slaves. While I am sure there are plenty of farms where these workers would find they were treated well, the simple truth is there’s always going to be a bad apple in every barrel. And unfortunately it’s the rotten ones you’ve got to regulate for.

There’s also the message greater participation in the TFW system would send to the general public. Currently farmers punch well above their weight in public support, though I appreciate it may not seem like that at times. But it’s true — agriculture enjoys greater public support and has a friendlier regulatory environment than almost any other sector of the economy I can think of. In no small part that’s due to how the public sees you as stalwart small businesses that regularly struggle with things like the weather not under your control. The TFW program infers more than a whiff of the plantation and makes you less sympathetic, especially if stories begin leaking out from farms managed by the aforementioned bad apples.

At its heart as well, I feel this call is based on a false premise, intentional or not.

I don’t buy the idea there aren’t Canadian citizens who could fill these jobs. I think there are plenty of people who would take on this work, the problem is the jobs aren’t good enough to attract them.

As employers you’re basically offering low wages, long hours and the guarantee of a layoff at the end of the season, then turning around and wondering why nobody is lining up. In a market economy, economic theory tells us, the solution is to change that. Make the jobs more attractive. If they’re more attractive, more people will be interested in them.

The study says higher wages aren’t the solution, and I’ll agree they’re not the whole solution — but they’re certainly going to be part of the equation. Better money can make potential employees ignore a host of other factors, as the energy industry proved in recent years, luring employees from far and wide to locations in the middle of nowhere with nothing but rows of bunkhouses, hard work and boredom.

Sure, with the margins on an average farm, it’s not likely to be easy to match that, but judging from the job losses in the energy sector in recent years — some analysts say as many as 180,000 may find themselves out of work eventually — you won’t necessarily have to.

Money aside, there are other issues that can be addressed.

One is the seasonal nature of the business. True, you can’t change that crops are planted and harvested when they are, but the farmers I’ve seen who have fewer problems with this issue are the ones who attempt to find year-round work for their employees. They operate side businesses trucking, seed cleaning and so on, or they find and cultivate employees who find seasonality works for them.

A lot of farms could also stand to up their human resources game. In an era where there are a lot of other options for prospective employees, you need to offer at least as good an alternative. That means predictability, doing the necessary paperwork and accepting that employees should be treated with respect.

One Saskatchewan farmer of my acquaintance always has no trouble filling up his harvest crew every fall. When one of the neighbours asked how he did it, his reply was succinct and to the point: “I bring them on, I put them on an easier job to start with, like running the combine, and I don’t yell at them.”

The numbers make the clear case that there’s a problem here the Canadian agriculture sector needs to solve.

But pursuing the easy solution to this problem is likely to spin off a whole host of new and larger problems.