For all the ink and vitriol that’s been spilled over supply management in Canadian agricultural commodities over the years, not much has changed.

There’s been a bit of evolution around the edges and some grudging concession on imports, but the fundamental bedrock of the system remains.

Now an earthquake could be coming, from the most unlikely of sources.

In 2012, the grandfatherly Gérard Comeau, a retired steel worker from Tracadie-Sheila, N.B., went to Quebec. While there he purchased 14 cases of beer and three bottles of liquor, for about half the price he would have paid back home, a prospect sure to brighten the day of any beer lover.

Read Also

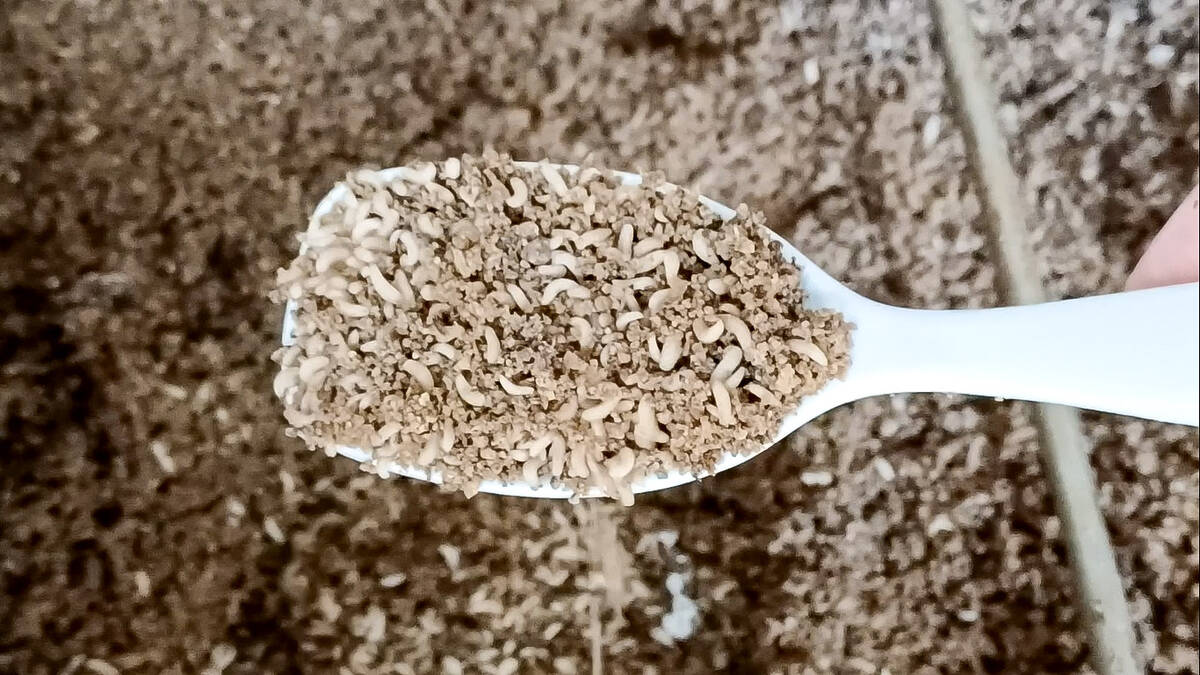

Bug farming has a scaling problem

Why hasn’t bug farming scaled despite huge investment and subsidies? A look at the technical, cost and market realities behind its struggle.

It was during the drive home he encountered trouble, in the form of the RCMP, who stopped Comeau and charged him with illegally importing alcohol, giving him a citation that would have cost him $300, had he chosen to plead guilty. He was legally entitled to bring home only 12 pints of beer and a single bottle of liquor.

However, a guilty plea wasn’t the route he chose to take. Instead he decided to challenge the legality and constitutionality of the arbitrary limits on what he could bring home.

Four years later, in 2016, the case finally saw the inside of a courtroom. There, Comeau found an ally in provincial court Judge Ronald LeBlanc and his interpretation of Sec. 121 of the 1867 Constitution Act, which is still a major part of the country’s governing framework. That section states products from one province shall “… be admitted free into each of the other provinces.”

To LeBlanc, that meant exactly what it said, and Comeau was in the clear. To New Brunswick prosecutors, that was a fundamental misinterpretation of a law they took only to mean that duties couldn’t be charged, rather than limits being set. That’s set the stage for a legal showdown at the highest levels that could have profound implications.

First they asked the Federal Appeal Court to hear the case, which the court declined to do, amounting to an endorsement of LeBlanc’s interpretation. The prosecutors then appealed that decision to the Supreme Court, and a hearing is now scheduled for later this year. If this decision is upheld at that level it could have many ramifications and many different forms.

It could narrowly cover alcohol only, or even limit the application of the decision to this single case. At its greatest breadth it could overturn precedents and governing decisions running as far back as the late 1880s.

Among the many business interests jostling for a seat at the table are the five supply-managed commodities that contend the livelihood of those farmers is at stake because the ruling as it stands could undermine the system.

Among the issues at play for the sector include provincial barriers such as Quebec’s and Ontario’s bans on moving chickens to processors in other provinces and barriers to buying and selling quota between provinces. It could very well kick off an internal “race to the bottom” that the sector has spent decades trying to avoid or see buyers play provinces off against each other.

To many farmers under that supply-managed umbrella, it might seem like yet another blow for the stability of their operations. To others, however, it might seem more like an entrepreneurial opportunity to be seized.

One thing that is certain is the change, in its broadest form, could be significant and kick off a period of potentially painful readjustment or the need to reorganize on a truly national level.

If history is a reliable yardstick, we can look at what happened when the Prairie grain industry underwent a period of deregulation and consolidation beginning in the 1980s. Murray Fulton, an agriculture economist at the University of Saskatchewan, has long contended the reason the Prairie Pools failed is they’d grown up in the closed ecosystem of heavy regulation and weren’t nimble enough to succeed when that framework was removed.

A bit further back in time, here in Manitoba, there’s another very interesting historical example.

In May of 1849, Pierre-Guillaume Sayer and three other Métis residents of Red River Colony were brought to trial for violating the Hudson’s Bay Company charter by illegally dealing in furs.

In the style of rough frontier justice of the time, 300 armed Métis, led by Louis Riel Sr., gathered outside the courthouse as the hearing was held. The four were convicted, but no punishment was imposed, setting an informal precedent that essentially gutted the HBC monopoly.

As this modern court challenge is underway, the supply-managed commodity organizations and the farmers themselves should be considering how prepared they will be if the unthinkable happens.