The rubber has hit the road in U.S.-Canada trade negotiations and the news isn’t good for Canadian dairy producers.

It appears they’re set to lose as much as 3.5 per cent of their market to tariff-free U.S. dairy imports. That’s on top of similar concessions made during negotiations for the Canada-European trade deal that saw a previous three per cent of the dairy market opened to competition.

- Read more: Outrage, acceptance greet Son of NAFTA

Read Also

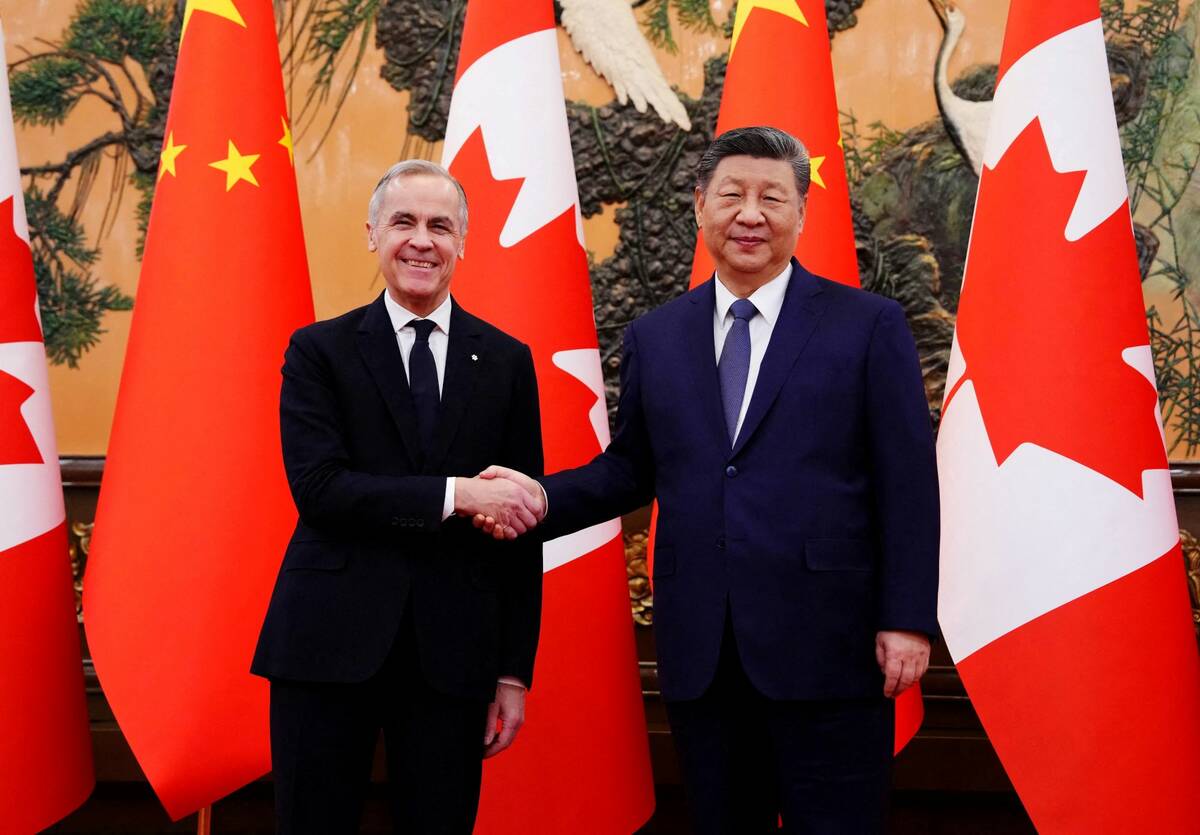

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

The infamous Class 7, established to go head to head with milk ingredients entering Canada from the U.S. tariff free, will be phased out within six months of the agreement coming into effect.

Any way you slice it, these concessions will be a bitter pill to swallow in dairy barns from coast to coast. That means Canadian dairy will face significantly more competition from imports than has historically occurred.

- Read more: Dairy downer

- Read more: Dairy producers ‘deeply disappointed’

The real fear for producers, of course, is that this is just the beginning. A few years back, in a previous job, I had the opportunity to speak with Agricultural Economist Murray Fulton, of the University of Saskatchewan, about how agricultural policy in Canada tends to evolve and change.

His two-word description has proven a handy reference that thus far has proven prescient: punctuated equilibrium.

That means things tend to flow along for many years under a status quo situation, while pressure for change builds quietly below the surface. Eventually that pressure spills out into a shorter period of controversy, which drives change. Things then smooth back out, and another quiet period of equilibrium is established.

Where dairy producers can take some comfort however, is that so far we appear to still be in the middle ground of public debate, and they still have time to influence the discussion — though they won’t be able to do it alone.

There are 11,000 dairy farmers in the country, a nation with a population of 36.3 million. They can tout the benefits of their business to the national bottom line all they want, but unless they can make the case for a larger impact, that’s going to be a tough sell.

It’s when the scope is expanded to take into account the individuals and businesses that will be affected too that the numbers become much more compelling.

According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, there are 478 dairy processors across Canada, which employ 24,000 Canadians. While they may welcome cheaper raw ingredient, a case can also be made that their market share could be sharply eroded by cheap U.S. imports.

Bringing those Canadians on side could triple the size of the dairy sector’s voice alone.

A Boston Consulting Group (BSG) study, commissioned by the dairy co-operative Agropur, found the five largest cheese plants in the U.S. “… process the equivalent of Canada’s national milk production.”

BSG also warned butter production could be cut by 60 per cent on this side of the international boundary if the border were opened entirely, though fluid milk would only likely suffer a five to 10 per cent cut. Over time, its study stated, dairy production and processing would inexorably shift towards the U.S.

The bottom-line numbers from the study were stark. In the end the consultants found Canada would likely lose 40 per cent of its milk production and the Canadian economy would be down between $2.1 billion to $3.5 billion.

Most of the job losses, it added, would come in rural Canada, where they’d be especially hard to replace.

The challenge now for the dairy sector — and by extension the other supply-managed commodities — is to make the case for their worth, and the worth of the existing policy. Making that a more difficult task is the mind-boggling complexity of the systems that have grown up, piecemeal, over the decades.

Opponents of the programs can speak in pithy sound bites of the free market and paint the policies as an unfair and regressive tax. Occasionally we’re treated to the irony of a free market think-tank that ordinarily couldn’t care less about the average working Canadian, waxing poetic about this terrible injustice they’re enduring as consumers.

Meanwhile, the various producer groups are left speaking insider jargon about commissions, support prices, three pillars and other words and phrases that are unintelligible to the average Canadian. At times, to the outsider making an attempt to understand the industry, it can feel like one is a layperson attempting to speak to the priests at the temple.

That’s not a good position for farmers to be in as the fate of the system is increasingly being called into question. Maintaining it is going to require the understanding and political will of millions of voters, many of whom barely know what a cow is, much less a tariff-rate quota.

Bringing those voters on side is now the most important challenge facing supply-managed producers. Without them a few thousand farmers won’t be able to guide the national debate in any meaningful way.