I had the opportunity over Thanksgiving this year to reacquaint myself with driving a Peterbilt when the weather lined up to actually allow a few days of combining.

Actually, there were three Peterbilts, as my brother seems to be working with a collection.

There’s the best of the three, a nondescript brown unit that quietly gets the job done.

There’s the bright-orange former moving truck cab over that’s been fitted with a too-tall short shipping container for a box. It requires advanced acrobatics just to get into the cab.

Read Also

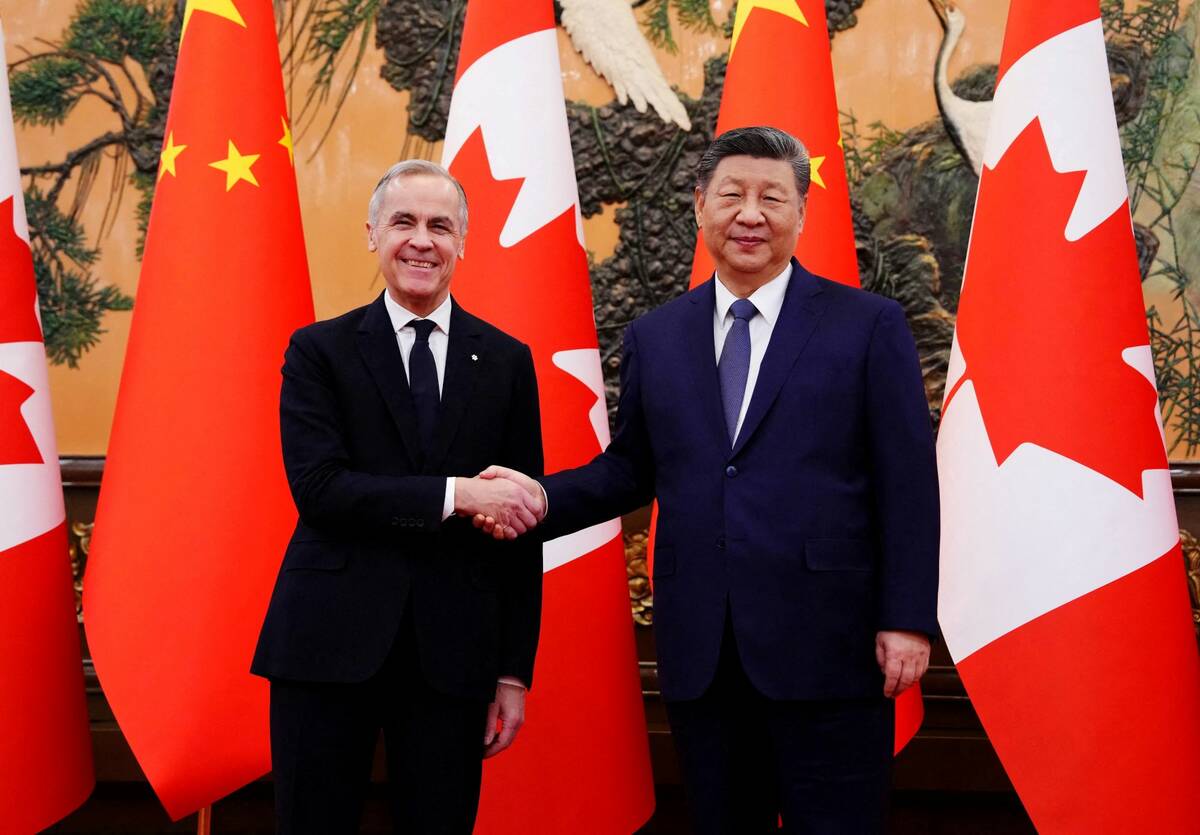

Pragmatism prevails for farmers in Canada-China trade talks

Canada’s trade concessions from China is a good news story for Canadian farmers, even if the U.S. Trump administration may not like it.

And then there’s the one with the distinctly pinkish hue that caused much hilarity the first time it showed up at the elevator and one of the agents ribbed Dad about it a bit.

He warned my brother that was coming, so he’d be prepared. And prepared he was… at the first mention of pink on his first trip in, he scoffed and shot back, “Are you colour blind? Anyone can see that truck is a manly shade of purple.”

Joking aside, the motley fleet works well enough to get the crop off.

What didn’t work out so well was the defective nut behind the wheel. I managed to remember how to shift properly before I did any permanent damage, but taking over running three strange machines in the dark and trying to sort it all out was, I admit, a bit of a challenge.

A challenge made all the worse because there was no rhyme or reason to how things were laid out. No two trucks had the light switches and dimmer switches the same. There were multiple shift patterns. Forget having the PTO controls in one uniform spot, and the list goes on. Try sorting that out by the light of a cellphone screen.

I was ruefully complaining about this in real time on Facebook and a farmer friend from out in the valley suggested I track down a headlamp with an infrared setting so I didn’t mess up my night vision. I told him I’d been wondering for the last three hours why every machine on the place didn’t already have one.

One thing this experience drove home to me is how quickly times change on the farm, and how long it’s really been since I was active on one. I’m about as current today as the folks who’d left in the late ’50s were in my day.

The last time I lived on the farm was the year after high school, and only for a few months of that. By the spring of 1989, I was a memory that came home for Christmas.

In the ensuing years there’s been many, many advances in the day-to-day operation of farms and it’s an amazing testament to the skills of the world’s agriculture engineers… but each of these advances can be a little daunting the first time you encounter it.

Take the self-propelled auger, for example. Watching me try to get it set up the first time was probably pretty funny to watch. I wish I’d been there. I was, however, being transported away on waves of frustration as I tried to master the slightly finicky controls on the fly.

And this is just garden-variety engineering and hydraulics. I don’t even want to think about how complex some of the higher-tech additions to the operation might stump me at first.

I’ve always said I’m not the smartest guy in the room, but I like to think I’m intelligent enough to learn, so I’m sure I could eventually dope most of it out. But there would be a learning curve, and it certainly got me thinking about the human resources challenges of the average grain farmer.

The Canadian Agriculture Human Resource Council pegs the agricultural worker shortfall in Canada at 59,000 and growing each year. It says that costs farmers in Canada $1.5 billion annually in lost sales. By 2024 its expected Canada will be lacking 114,000 agriculture employees.

There have been many responses to this. This past summer many farm groups, including the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, called for a revamp of the temporary foreign works (TFW) program to ease entry to Canada.

TFWs have undeniably become an important part of the business here in Canada, with the sector accounting for 62 per cent of approved TFW positions in 2017.

Initially they were employed towards the bottom of the skill chain, seeing service as fruit pickers, vegetable harvesters and so forth. But lately that’s begun to change.

In a report in the Calgary Herald Bryan Walton, CEO of the Alberta Cattle Feeders Association said some feedlots had workforces with as many as 10 per cent foreign workers. Likewise, many honey operations appear to count on imported labour for their short but extremely busy season.

However, I’ve yet to see much evidence TFWs are making serious inroads on grain farms. Large, complex and expensive equipment no doubt is one barrier.

Accessing this labour pool will require some planning, but it might be time to consider a concentrated approach as a sector. I’m sure these folks are smart enough to learn too.