The next time you have an hour or two to spare, find your way to the National Centre for Livestock and Environment’s website and download a paper called: Moving Toward Prairie Agriculture 2050.

But be forewarned, while reading through it doesn’t leave one with any overriding sense of panic, neither does it leave one feeling particularly comfortable with our farming system as we know it today.

The document represents the best guesses of 23 scientists representing various fields of expertise presented at the Alberta Institute of Agrologists conference last month. As a forward-looking document, it offers a frank look at where we are today on the Prairies and lays out some of the challenges that could change agriculture’s path into the future.

Read Also

Farming still has digital walls to scale

Canadian farms still face the same obstacles to adopting digital agriculture technology, despite the years industry and policy makers have had to break them down.

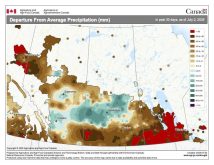

As can be expected, there are some positives but also negatives in store. The Prairies are no stranger to a variable climate, but it is the intensity of the various hot, cold, wet and dry extremes that is of concern as well as the changing disease, weed and pest cycles.

More land might become farmable as the mean temperature rises and growing seasons become longer, but increased moisture contraints may limit the productive capacity of land already being farmed.

Instead of becoming the new Iowa as some have suggested, it might be more realistic to think South Dakota instead, these academics suggest. Corn and soybeans are making inroads into some areas, particularly the eastern Prairies, but the dominant three crops on the Prairies — wheat, barley and canola — won’t be pushed from their pedestals.

On balance, a warmer Prairie climate doesn’t bode well for the pollinator community, largely because the stressors such as the varroa mite will be harder to control. Invasive species, such as the Africanized killer bees, are expected to make their way northward.

The weed spectrum will become more complicated. Winter annuals are already becoming more of a problem. As well, weeds that have developed resistance to one or more herbicides, including glyphosate, in the U.S. are moving northward. On the upside, the ability to grow a more diverse range of crops, including winter crops and warm-season crops, increases a farmer’s ability to employ integrated weed management.

- From the Grainews website: Diversify rotations to slow resistance

Fusarium head blight is expected to thrive in the changing Prairie climate; the mycotoxins associated with it are shifting too. Expect new pests such as new types of nematodes, especially if farmers develop favourites and follow tight rotations.

On the livestock front, warmer winters could reduce overwintering costs for cattle producers, the majority of which have switched to winter grazing systems — except that the increased frequency of extreme weather could create shocks that threaten herd health. Anthrax and liver flukes may become more common.

There will be impacts on grain storage, handling and transportation given the warmer temperatures and increased likelihood for dramatic swings in temperature. Consider this spring’s warning from the Canola Council of Canada on the potential for spoilage of canola in storage due to a quick move to warmer temperatures.

Ports such as Churchill will likely see a longer shipping season, but the railway line servicing it will be affected by the melting permafrost.

How will the world trade be affected because of changing supply and demand and the surge of bilateral trade agreements in the absence of a world trade deal? Can the insurance schemes in place keep up? Is the industry prepared to address the challenge of adaptation.

AAFC scientist Henry Janzen outlines the need for a comprehensive adaptation strategy that looks beyond the economic opportunities and one that can “envision the range of unfolding possibilities for future lands, and to devise measures that will be robust across a long time, even in the event of certain surprises.

“Ironically, some of the best insights toward this future perspective may be found in the past, by asking: Which metrics have survived the tumultuous changes of the past century or so? Some of these, such as soil carbon, ecosystem nutrient balances, diversity of farming systems (including livestock) might well be melded into future metric systems.”

Prairie agriculture has been in a dynamic state of flux ever since the Selkirk settlers arrived here just over 200 years ago, so it comes as no surprise that it must continue to evolve. In today’s context however, it’s important farmers don’t lock themselves so tightly through investments and contracts they can’t continue to adapt as their environment changes.