U.S. Wheat Associates and the National Association of Wheat Growers recently released the results of a study they commissioned on how much farm supports in four key markets are costing U.S. farmers.

The premise behind the analysis, conducted by Iowa State University economists, is that countries such as Brazil, India, Turkey and China are depriving U.S. farmers — and likely farmers in other wheat-exporting countries such as Canada — of sales by encouraging their own farmers to produce wheat.

“Wheat support policies and trade barriers encourage domestic production and depress world prices,” the study says. “Removal of these policies, which reduces domestic wheat prices, results in a reduction in domestic production and an increase in domestic consumption. Lower supply and increased demand lead to higher global prices of wheat, which tend to benefit wheat-exporting countries.”

Read Also

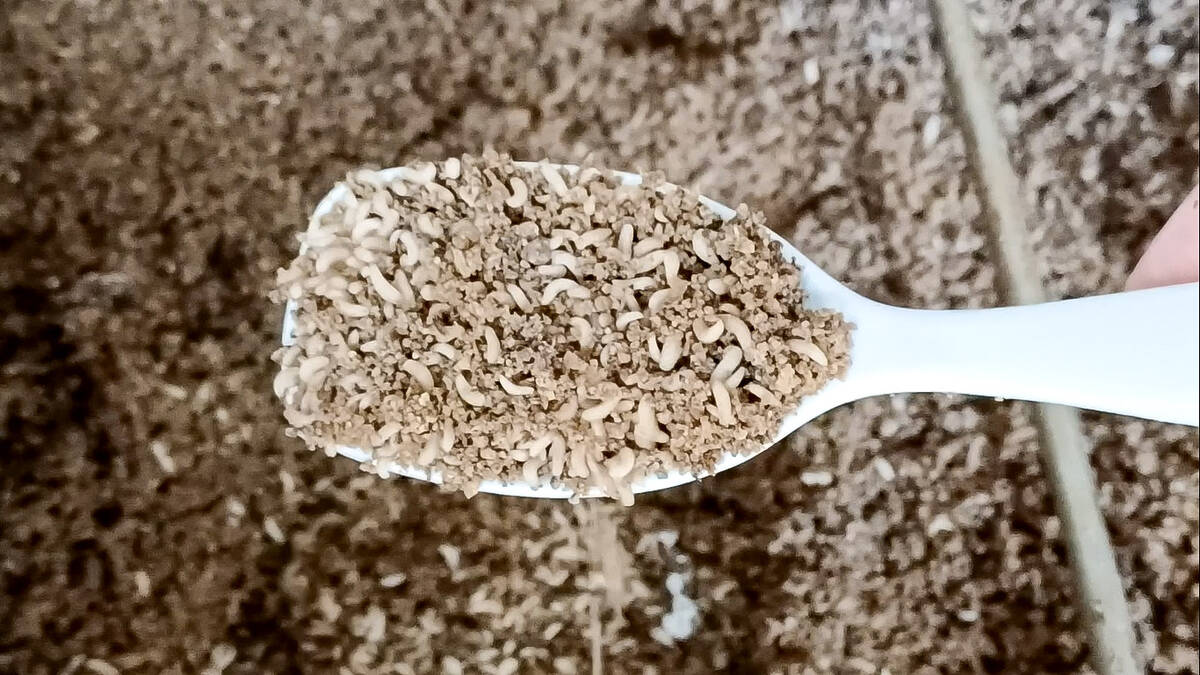

Bug farming has a scaling problem

Why hasn’t bug farming scaled despite huge investment and subsidies? A look at the technical, cost and market realities behind its struggle.

However, economists with the University of Tennessee counter that those countries, with the exception of India, are net importers of wheat.

“One of the definitions of trade-distorting behaviour is the exporting of a product at a price lower than the cost of production,” note Harwood D. Schaffer and Daryll E. Ray. In their view, the notion that domestic subsidies in those countries distort trade is “weak at best.”

The U.S. wheat study is premised on the notion that domestic supports for wheat production displace sales from the lower-cost producers elsewhere. It seemingly makes sense to minimize the total cost of food.

While that may be the case, the economic assumption is that trade should rationally flow to the lowest-cost supplier, and if that isn’t happening, there is something wrong with the world.

Perhaps there is, but for all the right reasons.

As Schaffer and Ray point out, nations have a compelling need to ensure their populations are fed and their most reliable insurance on that front is domestic production — even if it is more expensive.

“Food security for many countries is what military security is for the U.S. Short of brutal force, no government is able to survive the reaction of a starving public,” they write.

The hunch from here is that policies that foster political stability and economic growth are more of an asset to trade than a hindrance.