Greg Archibald and the staff of the Pembina Valley Water Co-op spent the first days of May steeling themselves for a really bad week.

The co-op, which supplies potable water to about 50,000 people in south-central Manitoba, was watching its three water treatment plants with a hawk’s gaze, after a string of April storms swelled rivers, including the Red and Boyne rivers, sent roads under water and turned fields into miles of uninterrupted lake.

Read Also

Tie vote derails canola tariff compensation resolution at MCGA

Manitoba Canola Growers Association members were split on whether to push Ottawa for compensation for losses due to Chinese tariffs.

- No crop insurance seeding deadline extensions planned: MASC

- Heavy rains slow seeding progress, acres well-behind five-year average

- Manitoba announces disaster flood assistance

Quality issues, thanks to the roiling flood waters stirring up sediment, had already reared their heads in the co-op’s northernmost plant on the Stephenfield reservoir. Particulate levels in the water were “just unbelievable,” Archibald, the PVWC’s CEO said, while a similar issue launched a boil water advisory in the City of Morden, one of the co-op’s members.

By May 4, an engorged Red River had reached 789 feet at Emerson, six feet below dike height and close to levels seen during the 2009 flood.

Roads throughout southern Manitoba had been closed, were running over, or had washed out. Staff faced issues getting in to work.

It’s hard to believe that, seven months ago, the co-op was worried about running dry.

Why it matters: Manitoba’s water management landscape is having to adapt fast with an increase in weather extremes, such as those that have brought the province from historic drought to serious flood in a matter of a few months.

Last summer, water levels across the region had drawn low enough to spark widespread restrictions through the Pembina Valley and Red River Valley.

The PVWC, meanwhile, had to lower intakes as levels on the Red River dropped.

As of Aug. 25, Red River flow at Emerson had slowed to a crawling 328 cubic feet per second.

“It did not stop flowing, but for us it was terrible because it went too low… so our intakes and our pumps, nothing worked,” Archibald recalled. “We had to get portable diesels and then eventually electric and put temporary intakes and temporary pumps and we ran them from June through to December.”

It’s a far cry from May 4, when Emerson flow rates had jumped to 66,000 cubic feet per second.

It’s the type of swing that Manitobans have been warned to expect more of.

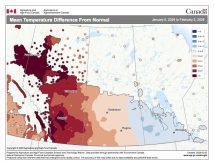

Experts like Danny Blair, co-director of science at the University of Winnipeg’s Prairie Climate Centre, have repeatedly forecast more extreme weather due to climate change. Manitoba can expect a higher average temperature moving forward, he said during an online presentation to farmers earlier this year, and while that will likely come with a longer growing season, farmers may also expect wetter springs, falls and winters; hotter summers and less summer rain.

For the province’s water management experts, it means a lot of work ahead.

“The reality is coming before us right now very quickly,” Steve Strang, managing director of the Red River Basin Commission, said. “We kind of talked about it. We knew it would be coming. We just didn’t realize it would come so fast.”

Reactions, he said, must therefore be equally quick on the draw.

Building buffer

The future of water management in Manitoba should have a lot to do with the best value, Strang said.

Resources, after all, are comparatively limited when put up against an ever-longer list of projects on the wish list of watershed groups, local governments, residents, and umbrella groups like the RRBC or Assiniboine River Basin Initiative (ARBI).

Projects like reservoirs, wetland restoration or small retention projects have value on more than one axis, Strang argued, since those projects often pull double duty as both flood and drought management — holding back water when the goal is to slow the flow, while building resilience when rain is scarce. Those same projects tend to add nutrient filtering and wildlife habitat through a water system, he added, while reservoir locations are chosen for their connectivity to aquifer recharge.

“You’re not going to be able to hit every one of those checkboxes every time, but the hope is that if you have to address a problem in an area, you’re doing so with all of those considerations,” he said.

Reservoirs, specifically, Strang expects to be hearing much more about in Manitoba’s changing weather landscape.

The provincial government and local authorities can, of course, impose restrictions around consumption if water levels run low — something drought-stricken areas experienced in full last year. Strang argued, however, that the added supply cushion, and therefore the ability to dodge official restrictions, may well increase the popularity of reservoirs as a retention tool.

“Climate change is creating an atmosphere where we could be seeing major downpours in the spring and then hot, dry summers, so that’s going to maybe change the way we manage everything, including farming, including the management of water, all of it,” he said.

Small scale, big impact

In western Manitoba, those juggling issues in the Assiniboine River Basin are also looking for new footing.

In mid-April, the International Joint Commission (IJC the bilateral water management organization between the U.S. and Canada) released its final report on water management in the Souris River Basin, one of the Assiniboine’s major tributaries.

The IJC study board had been tasked in 2017 with assessing the basin’s operations, following major floods in 2011 and 2014.

The study board, “quickly found” that the inter-jurisdictional agreement finalized in 1989 is still meeting the broad strokes of its mandate, according to Rob Caldwell, senior engineering adviser for the IJC.

Likewise, infrastructure through the basin — including the Boundary, Rafferty and Grant Devine dams in Saskatchewan and Lake Darling Dam in North Dakota — was still doing its job.

That is not to say, however, that those control structures will not be seeing any improvements to their operation.

Saskatchewan’s Water Security Agency, for example, is gauging reservoir capacity, given the decades those structures have had to build up sediment, Caldwell noted, while small infrastructure changes are on the docket.

“They’re looking at those sorts of things,” he said. “They’re looking at improving the conveyance of water downstream of their reservoirs as well, so there’s some unrelated infrastructure such as railway trestles, for instance, that can, under very high flows, impede the movement of water through those sections of the river.”

The changes with the most difference, however, are more fine detail and small scale than major capital projects, according to the IJC, and should be steered by a newly formed adaptive management cowmmittee.

The committee would “look for means of improving the regulatory regime for all things, not just flood control but also water supply and other things such as water quality and socio-economic benefits,” Caldwell said.

Within ARBI, there is an awareness that “main stem reservoirs, like the one on the Assiniboine, are probably not going to happen,” executive director Wanda McFadyen said, although she added there is appetite for smaller, “off main stem” retention projects along tributaries and smaller waterways.

Like the RRBC, ARBI has been looking at the overall resilience of projects that hold water in reserve.

The group has studied outcomes from reservoirs in the Assiniboine-Birdtail watershed, McFadyen said, while work has been done on the use of reservoirs as flood control around Virden. Potential reservoir locations are also being assessed along the eastern Souris River, once water passes back into Manitoba, according to McFadyen.

“Some of those reservoirs off main stem will help resolve the problems of drought and potential flood. Are they the end all be all? It depends on the amount (of water) that comes, but they certainly have a place and a role on the landscape,” she said.

Maintenance

While water retention has been a repeat conversation in the Assinboine River Basin, a basin that already boasts a number of large structures, McFadyen also cautioned that the initial cost is far from the full bill of such a project.

“You can’t just build it and leave it,” she said. “There has to be an associated budget to maintain it.”

Likewise, once built, changes to the structure are costly.

The Shellmouth Reservoir north of Russell, for example, is showing its half-century age, McFadyen noted, while “the investment into upgrades and maintenance has maybe not been on par to where the level of water is currently coming into it now (with) the changes on the landscape.”

Holding back the 67-kilometre long Lake of the Prairies, the reservoir has been a critical flood control tool for the Assiniboine River since 1968.

Support

If Manitoba has a looming challenge ahead of it, however, at least attitudes around water management are moving in the right direction, according to Strang and Archibald.

Strang cited, for example, the province’s establishment of Conservation and GROW trusts, both multimillion-dollar funding streams that he says have significantly increased resources for watershed districts. Through those, he said, things like wetland renewal and small retention projects have seen revamped support.

Likewise, he said, awareness and co-operation between the different jurisdictions has been on a positive trend.

Archibald, meanwhile, pointed to Manitoba’s still-developing water management strategy, as well as Ottawa’s first strides towards a Canada Water Agency, both things that could impact the regulatory landscape around water.

“The new provincial direction and the federal agency, somehow if this could come together, I think it would help us planning better for water,” Archibald said, noting the comprehensive water planning process in places like North Dakota.

“That ability to have a good process, I think, is probably what we need to think about as we go forward, and it’s a timely thing right now,” he said. “The province is stepping back and looking at what is the strategy and how are they doing things. I think that would be an opportunity as we go forward.”

More needed

The positive signs, however, are still short of what Strang feels is needed in the long term.

The Netley Marsh restoration, for example, has aspects of it that are not eligible for funding under the Conservation or GROW Trust programs, he said.

A large wetland referred by the commission as the “kidneys” of Lake Winnipeg, the RRBC completed the first phase of the marsh restoration in 2021.

“I think we’re probably better off than most provinces,” he said. “I think we’re seeing legislation and changes that will do that… but I think we need to do more.”

There is also, McFadyen said, the pitfalls of jurisdiction, and the importance of a “trans-boundary perspective.”

Inter-jurisdictional issues have been a historic sticking point for water management, with Manitoba forming the end point of drainage basins that span from North and South Dakota, Minnesota and Saskatchewan.

And increase in provincial funds is “amazing,” McFadyen said, but added that it will be critical to maintain a spirit of co-operation across political boundaries and to harmonize plans with what’s happening on a local level — such as Saskatchewan’s efforts to increase irrigation capacity, or North Dakota’s initiatives to flood-proof large swaths along the Souris River.

“The whole overarching water planning needs to be in effect,” she said.

The IJC report, she added, might be a driving pillar towards that goal.

The water co-op meanwhile, would also not say no to help on retention projects to increase resiliency.

Raw water ponds, for example, both allow water to settle before treatment, decreasing sediment, as well as hold months’ worth of water in reserve, Archibald noted. However, such ponds are also prohibitively expensive.

One such pond, which would have held a year’s worth of water for the Letellier water treatment plant, was priced out at $15 million, he said. Funding conversations have been had with the provincial and federal governments, but have so far not got a response.

The PVWC does have a raw water pond installed at its Morris location, with a capacity of about six months’ worth of water.

In an email to the Co-operator, a provincial spokesperson pointed to the $40-million to $45-million budget of the Manitoba Water Services Board. That budget includes support for water storage projects, regional water systems or other capital projects.

“Extremes in moisture, whether too little or too much, will always pose challenges,” they said.

The province has spent “hundreds of millions of dollars” in water and flood mitigation infrastructure, they noted, adding that the provincial water strategy will cover stronger trans-boundary ties, between planning for both drought and flood, better communication with stakeholders, and more consistent water supply.

“This being said, we know there is more to do as we continue to build our resilience to a variable and changing climate with more extreme events,” they said.