There are a couple of problems when it comes to the education pipeline that would launch new truckers out of the classroom and into the industry: There aren’t enough students coming in and, once they’re on the road, there are not enough who stay.

That’s according to the Manitoba Trucking Association (MTA).

Read Also

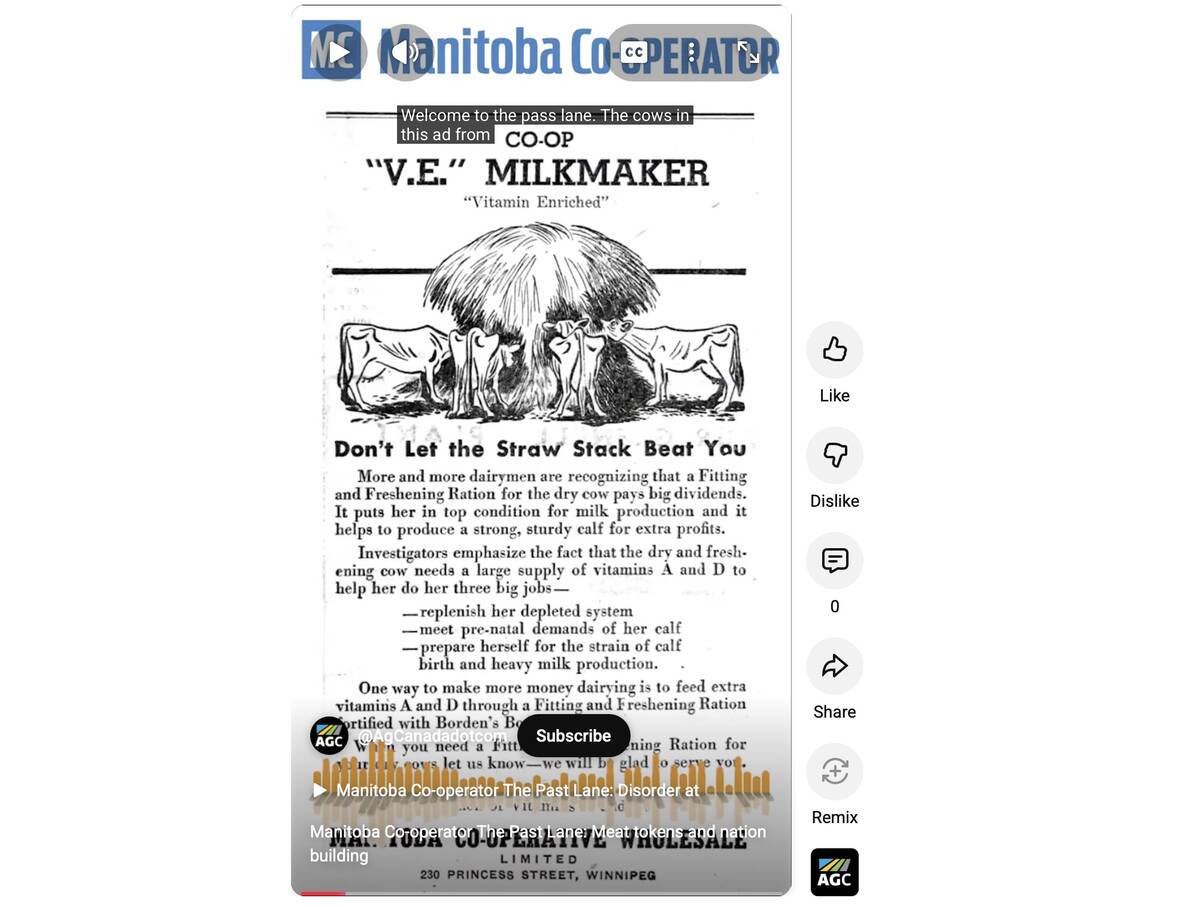

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

“Right now, with a shortage of labour, everybody’s doing what they can to keep drivers and, if there’s an opportunity to make more money somewhere else, we see drivers go from one company to another,” MTA executive director Aaron Dolyniuk, said.

“There’s not enough people coming into industry, currently, to keep up with the market demands.”

Why it matters: Transportation shortages in Canada have garnered the limelight thanks to widespread shipping delays.

Like pretty much every transportation-related group in Canada, the MTA is worried about staffing.

Lack of truckers has been an issue for years, while industry has argued that the pandemic has exacerbated shortages. By the third quarter of 2021, according to estimates from Trucking HR Canada, almost 23,000 trucking jobs nationwide were sitting empty.

A significant number of drivers get certified, only to be turned off by the realities of the time away from family and lack of amenities, which they often feel are not offset by enough pay, industry experts have argued.

It’s one of the reasons that the MTA would like to see a screening tool to hone in on long-term employees.

The MTA used to have a joint program with Manitoba Public Insurance (MPI) that included some aptitude testing, Dolyniuk noted. That entry-level driver training program also had tighter connections with industry, he said, and included a list of pre-vetted employers in the training process.

“They had some skin in the game. They had to do some training. They had to employ coaches,” he said.

Employees would then go from the employer to complete their certification at a third-person provider.

There is also opportunity for better training, and thus more confident employees, once they’re on the job, the MTA argues.

An enriched training environment might have more chance for “a regimented regime of on-board” training, meant for drivers who are certified, but lack experience or need company-specific knowledge to excel, Dolyniuk suggested.

“Once someone has their Class 1 licence, it still takes a bit of time before they’re a skilled professional truck driver,” he said. “The competitive nature of our industry is such that there just isn’t the margin to have drivers doubled up in the cab, one coaching another.”

Only a few, larger, companies, can muster the staff to pursue that type of coaching, he noted.

Remon Yang, owner of the Professional Transport Driver Training School in Brandon and Winnipeg, has also noted the rate of turnover. He also argues for post-graduation training.

Some graduates get certified in Manitoba, but then pursue jobs out of province, he said, while others find the job does not suit them, in some cases because of a lack of on-job training.

Adding more of those opportunities would “better facilitate the quality of the drivers,” he said.

If it can’t happen in house in a company, he argued, it could happen with more partnership between the employers and schools.

“Right now, only a few of the companies that we know provide the job-site training, but that is essential to keep the drivers in the industry — that they feel confident and comfortable enough to drive by themselves before they (employers) just throw a key to the drivers who graduate from the school,” he said.

Funding nuts and bolts

According to the province, potential truckers can get financial help through the Skills Development Program, under the Department of Economic Development, Investment and Trade.

Last year, the province spent just over $6 million to fund Class 1 driver training, Dolyniuk said.

According to Yang, up to 100 per cent of course costs at their school may be funded, although each application is highly individual.

Every student must have a letter of acceptance from the school and letter of intent (a conditional employment letter). From there, government decides if and how much funding is approved, depending on an individual’s circumstances. Other things, like English fluency, may also enter the discussion, Yang said.

Before any of that, however, potential students must complete their Class 1 knowledge test, air brake test and get a medical upgrade through MPI.

Once accepted, and having jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, potential drivers have two options to complete their Class 1, a 244-hour program, or a MELT (Mandatory Entry Level Training) program.

The 244-hour program is spread over six weeks, Yang said — two in the classroom and six in the cab and yard. The program also includes two attempts at the MPI road test in the last week.

According to Manitoba Public Insurance, a MELT program must have a minimum 121.5 hours of instruction, split between yard, cab and classroom.

In September 2019, the province started requiring potential drivers to complete a MELT program, or the already existing and more intensive 244-hour program, before booking a Class 1 road test. The program was unveiled nationwide, following the 2018 Humboldt Broncos tragedy.

MPI recognizes 29 driving schools approved to offer MELT programs in Manitoba.

Without funding, Yang says the 244-hour program at his school would cost $8,950.

Improvements

More accessible job postings — and therefore letters of intent — are among Yang’s suggestions to improve driver training in Manitoba.

His own company, he noted, maintains a list of interested employers.

Better training quality is another item he would like to see checked off.

The issue of education also dovetails with one possible labour solution touted by industry. Groups like the Canadian Trucking Alliance have called on the federal government to help increase access to foreign labour and temporary foreign workers.

Only the U.S., however, has licence reciprocity with Canada, Dolyniuk noted. Employees from anywhere else must go through normal licensing.

“I don’t think we’re looking for a changing of the rules,” he said. “What we’re looking for (is) streamlining in shortening up the process. We have many members that employ people through immigration and right now, it takes, in some cases, three or four months from the time that someone lands here in Canada to have them self-sufficient and being employed and earning a wage because of the process of licensing and delays in getting road tests.”

The province did not respond to requests for comment as of press time.