The final touches are being put in place at Roquette’s $600-million pea protein plant near Portage la Prairie.

The huge investment by French plant protein specialist Roquette, has already had an impact on the Manitoba economy.

Since the project broke ground in 2017, Portage la Prairie has seen a massive economic boost.

“The community has been home to hundreds of contractors working at the plant. These workers purchased fuel, food, personal services and lodging in the city,” says Dominique Baumann, CEO for Roquette in Canada and head of operations for the global business unit plants protein.

In addition, he says that more than 20 new families have permanently moved to the community as a result of employment with Roquette.

But Baumann thinks the effects of the new plant will reach well beyond Portage la Prairie, transforming the Manitoba economy as a whole.

“We feel that Manitoba is perfectly positioned to become the Silicon Valley of plant-based protein,” he said during a recent tour of the facility. “With two new pea protein plants recently opened in the province, Manitoba is leading the way establishing itself as a hub for innovation in the plant-based protein sector.”

- Read more: Premium prices for premium peas

That’s driven by a skilled local workforce, sustainable energy in the form of the province’s hydroelectricity bounty, access to transportation routes, and proximity to the raw materials needed, which Baumann said makes Manitoba “… a natural fit for future growth and investment in the sector.”

Read Also

Boosting productivity could mean historic farm revenues

FCC report finds increasing productivity in the Canadian agriculture sector could mean $30 billion in farm revenue in the next decade

The Co-operator visited the site in mid-October, located on 200 acres of land, just west of Portage la Prairie.

Michelle Finley, communications and public affairs manager for Roquette Canada, who facilitated the tour, echoed many of Baumann’s sentiments.

“Strong transportation connectivity — rail, air, road — that makes it easy to get our finished products to our customers in North America and globally,” Finley said.

Increased investment, COVID challenges

In January of 2017, when the company announced its intention to build the plant, Roquette estimated the cost would be in the $400-million range.

However, as they were adjusting and fine tuning construction of the plant, they took the opportunity to include some upgrades to allow them to include a broader range of pea protein products to better serve the growing market demand. That bumped the cost up to the $600-million price tag mentioned earlier.

Several acres at the site are dedicated to what Finley affectionately called “Trailer Town” — where dozens of construction trailers house the teams that have been working to finish construction.

“It’s much smaller than when we were at peak construction,” notes Finley. “Last spring and summer, when we had up to 1,600 people here per day, you would have seen more than 150 construction trailers on site.”

That was a significant challenge during a pandemic. In fact, they did have a scare. Last November, things got a little dicey when a small group of construction workers came down with the virus, but those cases were the result of community transmission and carpooling.

“We did really well. We had no outbreaks here at the plant and we took very aggressive and proactive approaches to COVID management,” Finley said. “We had a testing clinic on site and mandated thermal monitoring and mask use long before other players in the industry moved to those protections.”

She notes that, to date, they still have no instances of COVID-19 transmission at the plant.

While their efforts were successful in averting the viral threat, the plant wasn’t immune to the supply chain challenges that most construction projects endured during the pandemic.

“Some of our equipment was delayed getting to Manitoba due to supply chain interruptions,” Finley said.

Given that much of the inner workings of the plant were constructed off site and brought to the site in pieces (skids), it meant those delays could have a cascading effect. But while that modular approach exposed them to logistical risks in the face of COVID, the procedure was essential to the building process.

“Building (the modules) off site is a safer and more efficient way to do it,” she said.

Once they arrived, the modules went in as planned and without issue — but that’s not to say the process was easy. Because the skids are so large, they needed to be craned into the workshops in a specific order. The skids were trucked in, lowered into place and then connected together. In some cases, the buildings would have been walled in after components were put in place.

Like NASA

With the bulk of the construction complete, it’s now down to the nitty-gritty details, external site finishing and fine tuning the huge complement of high-tech equipment.

“Because the plant is so automated, everything has to be connected and calibrated properly,” Finley said.

The automation Finley speaks of was on full display in the plant’s main control room, an area that bears more than a passing resemblance to a NASA launch control centre. During the site tour, there were close to 20 people in the room busying themselves at dozens of computer monitors arranged around a large, digital display wall.

They were mainly the team calibrating and tweaking the plant’s automation to get it ready for full capacity. Once all that work is done, it will likely be a little quieter, with only six to seven production operators and power engineers required to run the plant.

The plant will employ roughly 120 when running at full capacity.

“It is a fairly small number, when you consider the size of the plant and the amount of peas that we’re processing in a year,” Finley said, noting expertise and experience can’t be automated. The company currently has around 50 experts from around the world working on site.

“We’ve got people here from Spain, Italy, Lithuania and, of course, France,” says Finley. They also have microbiologists and agronomists working in laboratories within the building and out in the fields.

Quality control

When the plant is up and running at full capacity, it will take in between 10 and 12 b-trains a day, at its ‘pea reception’ building, a critical first checkpoint for Roquette’s quality assurance and traceability efforts.

“Our customers require complete traceability from field to plate,” she said.

When the drivers arrive, their trucks are bar-coded. The attendant in the building uses a joystick system to lower a probe into the truck and suck up a sample of peas. The peas are then visually graded and assigned a bar code.

“That bar code has all of the information about where the peas came from, who grew them and where they were grown,” says Finley. From there, the peas are off-loaded and put into their allocated silos.

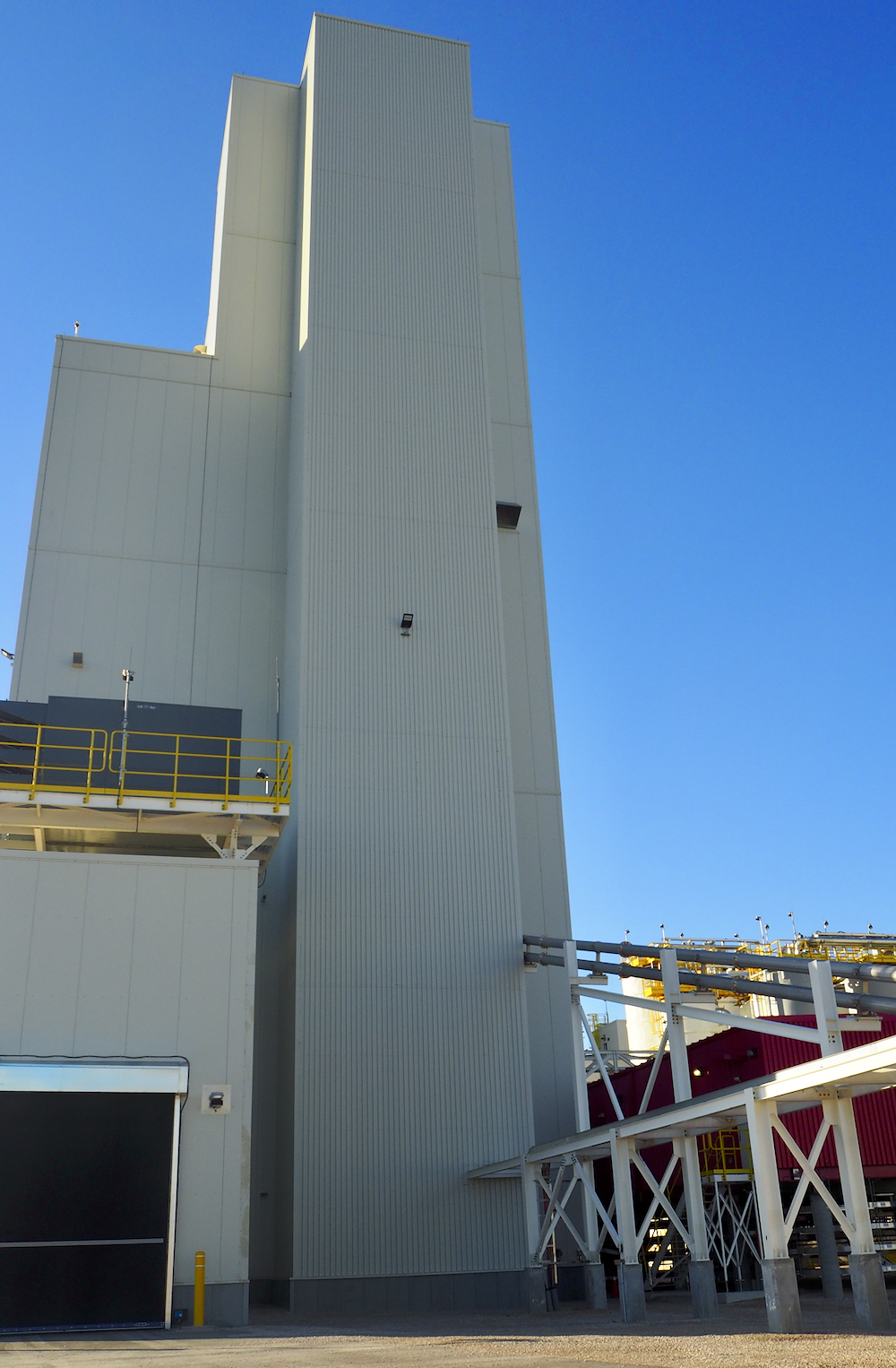

The next step sees the peas ground into flour at the facility’s 11-storey flour workshop; then water is added to the flour in the wet processing workshop and that’s where the protein extraction process begins. The resulting protein isolate is then packaged into 25-kg and one-tonne bags.

But before the final product is sold to customers, it must pass through more oversight at the quality lab, where they review things like protein and purity to meet customer requirements.

The final step is the sensory lab.

“What’s really unique about Roquette is that all of our finished products are sensory evaluated by Roquette employees,” Finley said. “We trained Roquette employees to evaluate the finished product using a number of sensory evaluation points.”

Employees who sign up for the sensory lab go through a very extensive training process where they have their palates trained to be able to identify different tastes in the finished product. The 14 members of the sensory lab team are from a cross-section of the organization. They could be a plant manager, someone who works in the packaging plant, an electrician or a millwright.

“Everyone is responsible for making sure that the product perfectly meets the needs of our customers and their requirements.”

The high-purity protein isolate that Roquette sells to its customers is used in many different products such as plant-based meat substitutes or ‘analogues,’ milk alternatives, peanut butter, ice cream, coffee creamer and nutritional shakes.

While the list of products that include pea protein is extensive, it is meat analogues that are driving a lot of the optimism in the pea protein market. And that is largely thanks to the launch of the Beyond Meat Burger in 2015, which Roquette is a supplier for. But how secure is that future? The Beyond Meat Burger launch was undeniably successful, but the products have had a start-and-then-stop introduction into the food-service sector, causing some analysts to question if this is another food fad.

Roquette says no, and stresses it is building a customer base that includes, but is not limited to meat analogues. Finley says the company expects to see continued growth in the alternative protein market. She points to a 2015 report from Lux Research saying alternative protein sources could claim as much as a third of total protein consumption by 2054.

Roquette’s CEO says the company is committed to investing in and building the sector.

“Our leadership position in plant-based protein was built thanks to a long-term vision with a huge investment plan and a strategy deployed all along the value chain,” says Baumann.

“Roquette is confident that consumer demand will continue to grow, and to meet the demand, we have invested more than any other company in our pea protein business.”

Roquette aims to have pea protein available next month for customer sampling and qualification.

The plant is expected to reach full capacity, processing 125,000 tonnes of peas, early next year.