Newly imposed animal welfare regulations in California will have little economic impact on the North American hog sector, an agricultural economist with the University of California Davis predicts.

“California consumers like me are going to pay, I don’t know, five or 10 per cent more for pork that’s covered by the policy, which means a pork chop, but not a cooked ham or lunch meat or sausages,” Dan Sumner told a Jan. 10 agricultural outlook webinar organized by the North American Agricultural Journalists.

“This covers about eight per cent of the sows in North America. The baby pigs that come from those sows that comply are going to cost more. And then I, as a California consumer, will pay.”

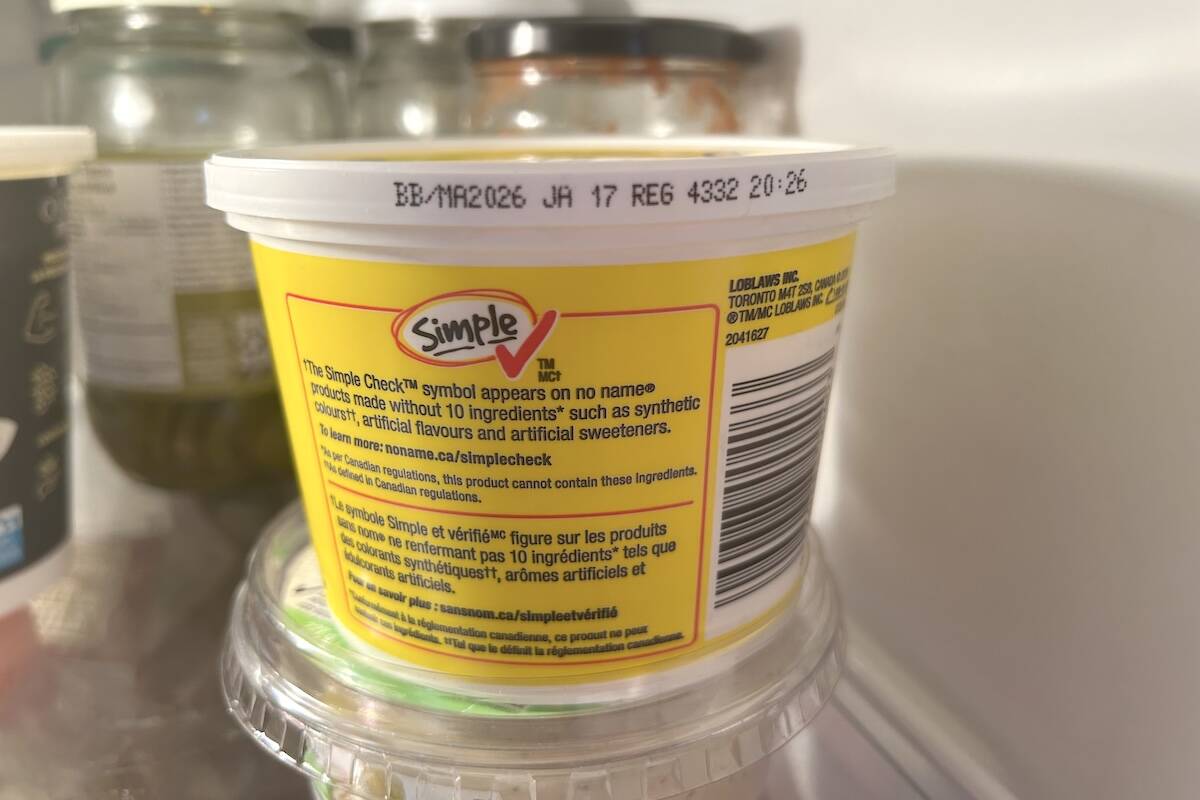

Read Also

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

Why it matters: The North American pork industry expects to struggle with a supply-demand imbalance through much of 2024.

Sumner said the California regulations don’t apply to pork sold into other domestic markets or exported.

“The other 92 per cent of the sows [or] the farms that raise those sows really won’t notice much.”

The controversial Proposition 12 (Prop 12), which was approved by California voters in 2018 state elections, stipulates sows supplying the state’s consumers must be grouped in housing that provides a minimum of 24 square feet per sow.

The new rule raised fear of increased costs throughout the industry, including in Canada, which exports about four million feeder hogs to the U.S. annually. Industry pointed to the cost of compliance measures and segregation needed to meet the new requirements.

The Manitoba Pork Council has raised concern around the precedent of the state-specific rule, which it said could disrupt the highly integrated North American market. The Canadian pork sector has also pondered the implications to U.S. trade obligations between Canada and the U.S.

“We don’t negotiate separate trade agreements with 50 states,” general manager Cam Dahl told Glacier FarmMedia in late 2023. “We need to be able to have a North American market that’s integrated, allows for the free flow of product and isn’t different in every different state.”

While the Manitoba pork sector estimates that about 60 per cent of sows in the province are already housed in group pens, producers have worried the pen sizes might not comply with the new rules.

Efforts by the U.S. pork industry to have Prop 12 struck down were nixed by the U.S. Supreme Court last May.

Sumner likened Prop 12’s market impact to the organic market, in which only those producing for that market face the extra costs of compliance, while consumers who choose to buy those products will pay higher prices. The main impact in that case would be on consumers in California, who voted by a wide margin to support the measures.

Asked whether the pork sector overstated the potential consequences, Sumner said some of the briefs submitted in court where perhaps a little “overheated,” but that is understandable.

“I understand why the pork industry, the political part of the pork industry, was concerned about Prop 12,” he said. “It was, just frankly, insulting … a bunch of people who had no connection to the pork industry telling other people how to raise pigs and insulting them to say, ‘you’re cruel people.’”

Sumner cautioned that, while he thinks the effects of Proposition 12 on the industry will be muted, there is risk that other states will also come up with a variety of regulations for meat or other food products sold within their jurisdictions.

“It becomes a real mess and then it starts to really have national implications or North American implications,” he said.

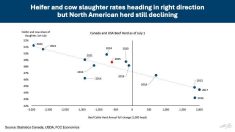

Roland Rumasi, head of RaboResearch Food and Agribusiness, said the biggest issue facing the North American pork sector in 2023 and into 2024 is imbalanced supply and demand.

Although USDA statistics show the U.S. sow herd declined by 1.2 per cent in the latter half of 2023, increased litter sizes in the remaining herd offset the decline in breeding stock. Rumasi said that when producers cull their herds, it’s natural to select the least productive sows for elimination.

“There hasn’t been a significant reduction in hog supplies,” he said. “We expect it’s going to take another half a year plus for that supply side to sort of fix itself. And then things could start to turn.”