Many beef producers got an unpleasant shock at last fall’s preg check, and experts are weighing in on what can be done to avoid a similar problem this year.

According to a report from the Western Canadian Animal Health Network (WeCAHN) over 40 per cent of some herds were found open. That was offset by more fortunate herds with two or three per cent open rates, WeCAHN said, but across all herds, open percentages ranged from 10-12 per cent, compared with eight to 10 the year before. That was even with a potentially weighted sample, as producers may have already gotten rid of open cows before testing, the report noted.

Why it matters: Canada’s beef herd is at its smallest in decades, and a smaller calf crop this spring won’t help.

Read Also

Air, land and sea join forces as Manitoba launches Arctic trade corridor plans

Manitoba wants to take its Arctic trade routes to the big leagues. The Port of Churchill, CentrePort Canada and Winnipeg airport have all raised their hands to help it happen.

Weaning weights were also scattershot. Some farms were up, but others saw much lighter calves. Those were largely the same farms with poor pregnancy catch.

The report pointed the finger at cumulative years of drought. Feed and water were in short supply or of poor quality, and poor protein and feed energy availability likely caused “low to no cycling over the summer.”

To illustrate the point, it went on, some farmers saw females start to cycle after they were put on feed in anticipation of being sold.

The abnormally high open rates match observations from Bart Lardner, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan and provincial strategic research program chair in cow-calf and forage systems.

“In some areas, producers have been dealing with three, four years of dry, drought conditions and certainly forage quality has been a big challenge,” he said.

At this point in the dry spell, he noted, “a lot of our breeding females, you know, they were conceived in a drought condition, born in a drought condition, raised in drought condition(s). Just talking to some other practitioners or vets during preg check time, even at heifer development time, (we’re) finding out that they’re taking longer to reach puberty.”

Their own reproductive tract development evaluations have noted heifers coming into the breeding season less physically mature than expected.

“They’re not catching in that first cycle,” Lardner said. “If they catch, it’s in the second or the third cycle, so that just delays them.”

Nutrition

It all comes back to nutrition, Lardner said.

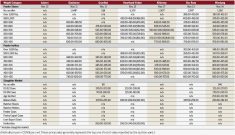

The link between body condition score (BCS) and reproductive success is well established. The Beef Cattle Research Council notes that cows with an ideal BCS rebreed up to a month earlier than underconditioned cows. They have twice the chance of conceiving, produce more milk and have fewer calving complications, abortions or stillbirths. Their calves tend to be healthier and heavier at weaning.

It’s key that females get enough protein and energy in the lead up to breeding season, Lardner stressed.

Unfortunately, conditions at turn out have been less than supportive in the last few years. As well as drought, cold springs and weather events have seen a string of years with delayed pasture regrowth.

Pastures should be at the four-to-five leaf stage, or running eight to 10 centimetres deep before they’re ready to support cattle, Lardner cautioned.

Overgrazing offers a similar nutritional problem.

Buying more feed is a hard pill for producers to swallow, particularly after multiple years of drought, poor forage harvests and high feed prices, but if the feed supply is dwindling, and the pasture isn’t ready yet, experts warn that producers might not have much choice.

“When you look at a cow’s nutritional requirements, the highest nutritional period is after calving,” Manitoba Agriculture livestock specialist Shawn Cabak said. “The cow is milking. They have to prepare for rebreeding. The reproductive tract has to get back into condition. They need energy in the low ‘60s (percentage of total digestible nutrients). Hay by itself will not meet that.”

Silage or grain or greenfeed are all higher energy supplemental feed options, he said.

Producers should also consider that fresh grass is mostly water, Cabak said. That has implications when gauging if there’s enough feed value on the pasture to adequately support a cow. “For a cow to meet its dry matter requirements, it physically needs to eat close to 200 pounds of forage at that high of a water level.”

Don’t forget the mineral

Producers may also want to take a close look at their mineral offerings.

Protein and energy deficits, and the corresponding drop in body condition, were big issues, reported WeCAHN, but liver biopsies also supported industry suspicion that copper deficiency was playing in.

“It’s important to note that serum trace mineral testing can be useful to identify problems such as copper deficiency, which may be linked to reproductive problems,” WeCAHN said, adding that option is both less invasive and less expensive and thus may be attractive to producers.

Water quality is one major factor. Poor water quality is linked to reduced feed uptake, while sulfates tie up copper.

Water infrastructure improvement, such as the installation of solar waterers or piping systems, has been increasingly stressed by researchers and industry extension staff in the last few years.

Lardner pointed to current federal, provincial and other funding programs meant to help farmers make those changes.

“It’s a very complex situation, mineral nutrition. It’s not straightforward,” he said.

Other than sulfates in the water, molybdenum in the forage can also tie up copper, he noted. High nitrates can be another lurking problem.

“You probably should be looking at testing your water. It’s not a difficult task, but at least you know what you’re starting with and saying, ‘okay, you know what? I do have a water quality issue and I do need to address it with proper micronutrient supplementation.”

Phosphate is also important for rebreeding, Cabak said.

Shopping for mineral options

Not all mineral supplements are equally bioavailable, Lardner warned.

Sulfate mineral options are on the low end of that spectrum, while more expensive hydroxy or chelated mineral will get better absorption.

How the mineral is presented will also impact how much makes it into the cow.

If the farmer is opting for granular free choice mineral, Landner suggested shopping around at three or four different companies.

“Read the formulation tag … Ask the salesman about the type and the ingredients and the form of trace mineral,” he said.

If cattle are still on feed, that mineral can be added in for more control over uptake, Cabak said. After calving, producers should target two to three ounces of mineral uptake a day.

“If they’re on a lot of legumes, a one-to-one mineral works,” he said. “If they’re on a lot of annuals…then a two-to-one mineral and probably even some extra calcium in there.”

Tubs with covers can also boost intake, he suggested. “When mineral gets rained on, it gets weathered, cattle don’t want to eat it.”

It may also be a matter of brand. Some brands are more palatable to cattle, Cabak said.

Lardner’s team has also recently completed research into injectable mineral supplementation. “At least you know the animal’s getting that level of copper, zinc and manganese in the injectable form,” he said. “Free choice can be all over the place.”

That is a more expensive option, he acknowledged, and new to Canada.

Lardner also warned producers not to forget about vitamins. Vitamin A and Vitamin E are “huge,” he said, and mature or high-fibre forage under drought conditions might be falling short on those nutrients.

Producers also have injectable vitamin supplement options. Or, he suggested, producers might want to look at a fortified mineral.