It’s no longer unusual to see a solar watering system on summer field tours, but extra planning is needed if producers need or want to use those alternate sources in winter.

Why it matters: Alternate watering systems got a lot of attention during the last year of drought, but proper planning can also make them a year-round investment.

Shawn Cabak, livestock extension specialist with the province, says Manitoba’s spate of dry years has led to more interest in alternate watering systems in general, especially in 2021.

Read Also

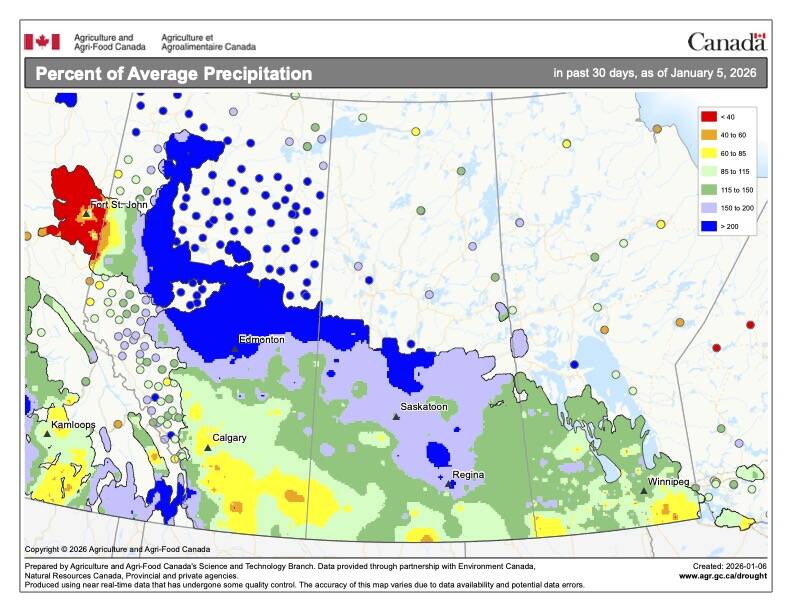

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

Low dugout levels turned out to be a sign of what was to come last spring. The industry had already flagged a potential problem coming out of snowmelt, knowing that winter precipitation levels had not been sufficient to refill surface water sources. Issues worsened in the following months with the lack of rain.

In June 2021, the province reopened funding for water infrastructure on farm, offered as part of Ag Action Manitoba’s beneficial management practice (BMP) stream. That program split the cost of new dugouts, wells and pipelines systems, as well as alternate systems powered by solar or wind, between the farmer and provincial government up to $10,000.

A second application window for the program opened in late 2021 to fund projects this coming year.

“We’re seeing maybe more drilled wells going onto pasture than we used to,” Cabak noted. “That’s becoming an option, and that can be tied either with hydro or with an alternative watering system such as solar, maybe wind.”

Welcome to winter

When it comes to solar systems, a winter system is always going to be more expensive than a summer system, Cabak noted

“They have to be engineered to a higher degree. They need more panels. They need more batteries,” he said.

It’s a point also stressed by Derek Verhelst of Kelln Solar, a Saskatchewan-based company specializing in remote watering systems.

The company’s pitch points to many of the often-cited arguments for ditching dugouts — pumping water out of a dugout or stream and into a trough keeps animals out of that water, keeps the water cleaner, limits foot problems, increases weight gain and improves riparian-area health.

In winter, however, it’s also about safety, according to the company. Verhelst argued that such systems keep both animals and people on land, noting that a number of their sales have come after a producer has lost an animal through the ice.

Winter considerations

If the producer does opt for a solar system, Verhelst urged them, in general, to avoid underbuilding the system. A system designed for current herd size might get outstripped if the herd grows, he noted, arguing that it is easier to plan for future growth from the start, rather than upgrading a system later.

That consideration is also key outside the warmer months. Fewer hours of sunlight mean batteries are working harder in the fall and winter, Verhelst noted.

It is also, he stressed, a numbers game when it comes to keeping the ice at bay.

Insulated troughs, for example, are covered across the top, except for periodic drinking tubes each 10 inches across, therefore limiting exposure to the frigid air. The real key, however, is water movement. Such troughs are sized so that a given number of animals will turn water over once a day, to keep that water from freezing, he noted.

“We have minimum requirements for our insulated troughs,” he said. “The thought being, the water coming into that trough is groundwater. It’s coming in at 4 or 5 C.”

“You do get ice buildup in those holes on cold days, but it can be chipped out or broken through by the animals,” he added.

Other options draw water up as needed from below the frost line.

A frost-free nose pump, for example, is based around a pressure system and requires no power, Verhelst said.

Those systems are installed either over a cased or bored well or next to a dugout, with hose feeding water into a reservoir from below the frost line.

“The cow goes up, uses its nose to activate a mechanical pump that’s in the water and then the cow gets water,” he said.

Excess water then drains back into the reservoir, to avoid icing.

A motion-eye system is a powered alternative with the same philosophy. Based on a gravity-fed well sunk 18 feet deep, the system’s motion sensors activate a powered pump to bring up water when a cow approaches, only to have that water drain back below the frost line after that animal moves away.

Various power sources can run that system, and Verhelst noted once again that capacity, herd numbers, solar panel size, and number of batteries must all be on the producer’s radar when opting for that design.

In terms of reliability, however, Cabak noted that the most dependable systems are still the ones based on hydro in the yard.

“When you start talking about alternative systems, working off of solar, generally they’re energy free, so they’re more subject to cold weather,” he said. “You need minimal livestock use out of the system so that you have that water turnover. That provides the heat in the system to keep it from freezing. The more use, the more water movement, the less chance of it freezing.”