Ryan Canart’s approach to pasture management reflects a lot of the principles that have become old hat during grazing tours across the Prairies.

He is among the proponents of rotational grazing. His 907 animals are mostly moved daily through relatively small paddocks, with a goal to grow soil health and productivity.

His land features an extensive piping system to bring water to those paddocks. He’s pursued a long list of sustainability oriented projects, and his ATV is fitted with a forage press of his own design, allowing him to test Brix level, a measure of sugar content that can be applied to forage quality.

Read Also

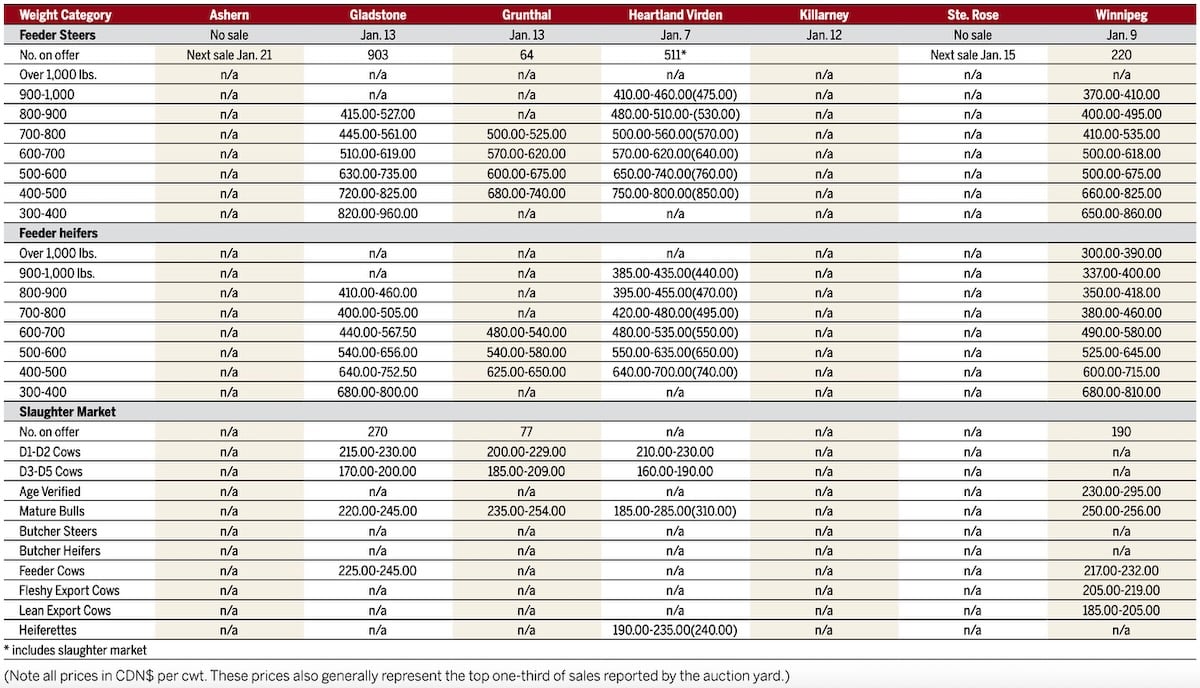

Manitoba cattle prices, Jan. 15

There is something that stands out about his operation, however. Not a single animal has been there for more than five months.

Why it matters: While cattle producers have been early adopters of regenerative ag practices like planned grazing, most of those operations are cow-calf.

Canart runs a yearling operation. Purchased animals arrive on his farm near Hargrave in western Manitoba in spring and they’re shipped out around Labour Day.

“We typically will start buying calves and backgrounding them in a feed yard somewhere up until somewhere around the end of May,” he said.

The calves are rarely familiar with rotational grazing. Unlike cow-calf operators who use the same philosophy and have calves born into the system, Canart must get his animals up to speed after arrival.

The cattle are offloaded into a fenced corral system and then exposed to a training paddock.

“I like to try and get them out fairly quickly, like within a day,” Canart said.

That paddock is well fortified with six-strand electric fence. From there, Canart brings out the temporary fencing, marked with flagging ribbon to ensure cattle can see it. That fence starts with two wires, and eventually dwindles to one as calves become familiar with the system.

“Usually, I kind of like to let them be a little hungry so that they’re more interested in the grass than just running around,” Canart said.

The calves’ first exposure is in a small area, usually an acre or two. The herd may only need an hour to clear the grass in that area, after which they are immediately moved to the next paddock to get them used to the pattern of movement.

“I’ll just sit there, and then when I can see that they’ve kind of consumed the grass and they’re starting to look around, I’ll come right out there and take that wire down and they’ll get the next little piece,” Canart said.

“I’ll do that two, three, four times in a day, and it’s amazing how quickly they learn that when that guy shows up … there’s going to be new grass.”

He has few problems with calves that don’t clue in.

“I’ve had cattle out [and] it seems like they’re almost ashamed … they just hover around [the fence] wanting back in with their buddies,” he said. “Definitely you’re going to get the odd one that gets pushed out.”

The draw of yearlings

Canart is among few Manitoba producers who opt for yearlings, let alone those who also use rotational grazing.

A sector profile of the cattle industry, released by Manitoba Agriculture, estimated that cow-calf operations made up 77 per cent of the province’s cattle herd in 2022. Feeder and stocker operations accounted for 15 per cent, and seven per cent were on pure feeding operations.

Canart’s father also opted for yearlings in the western Prairies, he noted. It’s a system that can be run without owning land and without the infrastructure needed to winter cattle.

In some years, Canart noted, there is also an argument for better return. He made the comparison between a short-term stock market trader and one who is in it for the long haul.

Building the plan

Looking back, Canart says it’s hard to recall how he landed on his training regimen.

He had plenty of headaches in the years before he started his current system. Calves did not know to look for the regular moves, and the result was wrecked reels or animal injury.

“I think maybe I just became more and more comfortable with confining them with the temporary wire and eventually I just decided, ‘You know what? Let’s just do this – move, move, move, move,’” he said.

“It’s not fun to have a wreck when you have a temporary wire and a bunch of cows run through it.”

Hurdles

No system is all pro, no con, Canart’s included. Because he is constantly buying calves only to sell them a few months later, market volatility is a risk.

High cattle prices now, for example, require the price to stay high long enough for Canart to get the calves grown and back to the sales ring. That part of the business is masterminded by his brother.

Canart also holds an off-farm job as general manager of the Assiniboine West Watershed District, which provides a financial buffer.

In general, however, there might be benefit to adding yearlings to the farm, according to 2018 materials from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

A blog post published on the university’s website by beef nutritionist Travis Mulliniks said that drawing on multiple cattle classes, such as splitting the cow herd with some yearlings, offered more flexibility in grazing strategies and herd management that could be particularly valuable in drought years.

The post did warn producers to be wary of higher costs of production and higher risk, “which may not justify the potential added net returns for a risk-adverse producer.

“However, the use of flexible grazers is a management tool that cow-calf producers should consider adding to their operation as part of a drought risk management plan to increase management flexibility and profitability.”