The list of new inductees to the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame includes two Manitoba men.

Digvir Jayas and Ashok Sarkar were noted for the innovation and leadership provided to Canada’s agricultural landscape.

Why it matters: Every year, Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame accepts nominations based on an individual’s outstanding contributions to the agricultural and food industries in Canada.

Read Also

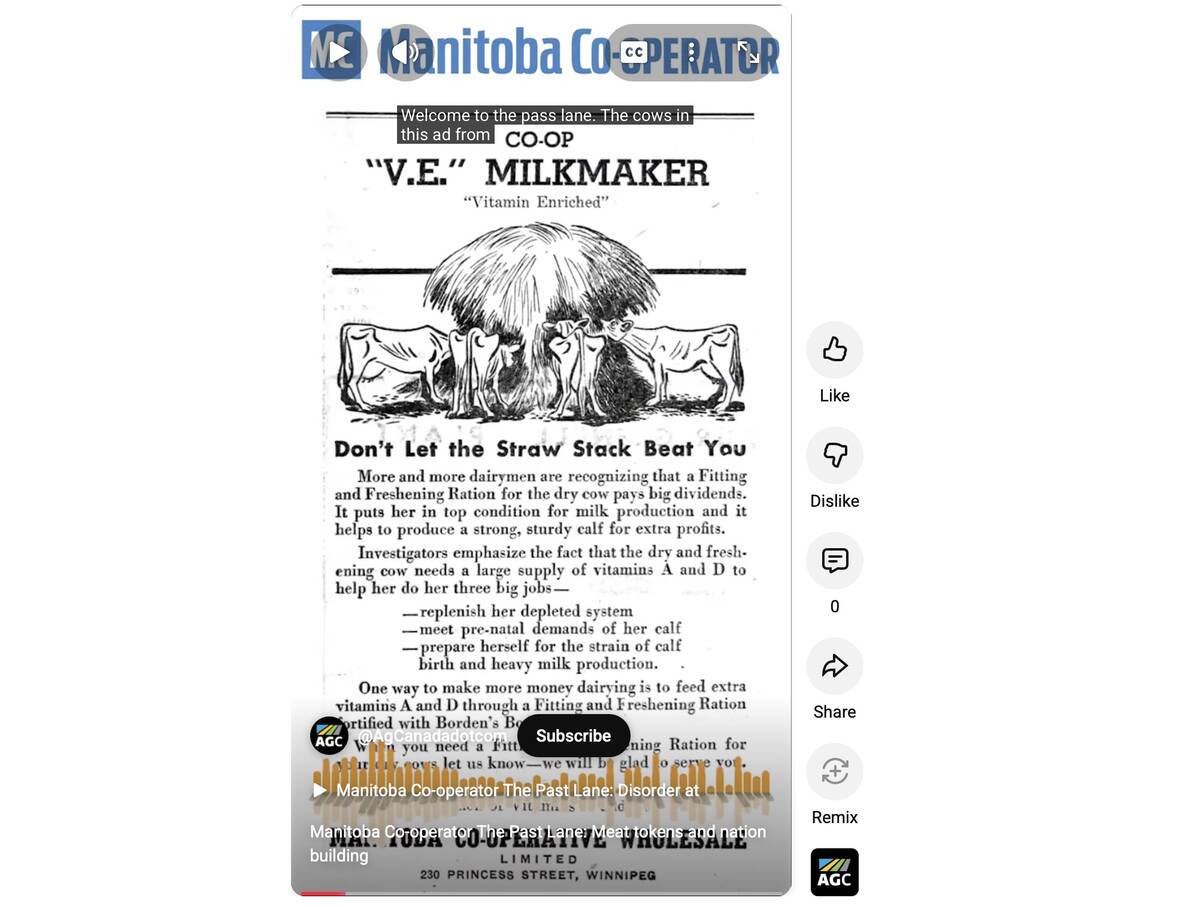

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

Digvir Jayas

For more than 30 years, Jayas has been the Canadian leader in agricultural research on the stored-grain ecosystem, working to improve food security by minimizing losses in stored grain. His research team at the University of Manitoba developed the concept for horizontal airflow grain drying.

Jayas took an interest in grain storage early in life. He grew up on a small farm in India and, while travelling the countryside, saw a lot of grain spoilage. He heard farmers complain about bug-infested, mouldy or smelly grain.

“I was not thinking of doing a PhD at the time, but I remember thinking this should be a solvable problem,” he said.

Those early experiences stayed with Jayas through his schooling and were instrumental in deciding his career path. He knew he wanted to go into engineering and was strongly considering electrical engineering, but his memories of farm life swayed him toward the agricultural side of the discipline.

“I wanted to do things which could be used on the farm,” he said.

And while the idea of food spoilage was in the back of his mind, his motivation was to help with the modernization of agriculture in India.

“There was not a lot of mechanization in India,” he said. “There were certainly tractors and some land preparation equipment, like cultivators, but a lot of harvesting was being done by hand. So I think that’s what got me more inclined to the agriculture side of engineering.”

Jayas finished his bachelor’s degree in agricultural engineering in India before coming to the University of Manitoba in 1980 for his master’s education. He later earned a doctorate from the University of Saskatchewan and took an assistant professor position at the University of Manitoba in 1985.

He rose quickly through the academic ranks, becoming a full professor in 1993. In 2009, he was appointed vice-president of research at the university, which was expanded to include international relations in 2011.

Jayas may be best known for the aforementioned horizontal airflow drying system, an idea he conceptualized early in his career.

“From the beginning, I have taken the approach that grain is a living entity, and it is affected or infested by living entities like insects, mites and micro-flora. So, the interaction between the biological and physical factors is what causes the spoilage. … To manage or to reduce this spoilage, we need to understand that interaction.”

That led to development of the horizontal airflow drying system and, ultimately, a solution to the food spoilage problem that perplexed him as a child. It took time to convince bin and drying equipment manufacturers of the benefits of the system, but today it is widely used.

Jayas insists his success, to a great extent, stems from the people around him.

“It’s the high quality of the graduate students who chose to work with me,” he said. “I use that word ‘choose’ because they were all very bright and they could have gone anywhere.”

If he counted all the graduate students, post-doctoral fellows, research associates and visiting scientists who have worked with him, Jayas says it would be somewhere north of 200.

“Most of them are working in the field and are contributing to reducing food spoilage around the globe. That, to me, is the most satisfying. It’s almost like when your kids do well, you feel proud of them,” he said.

Through his career, Jayas received many accolades. Most recently, in June, he received the Engineers Canada’s Gold Medal award, the organization’s top honour.

While Jayas says it’s humbling whenever a professional is acknowledged by their peers, the induction into the Canadian Agricultural Hall of Fame is special.

“In this case, the accolade is from the users of my research. And that brings much more satisfaction and value because the users of the research are the ones who are appreciating the work.”

Ashok Sarkar

With a career spanning more than half a century, Sarkar’s work centred around promoting the quality of Canadian wheat and other grains to markets around the world. He spent most of those years at the Canadian International Grains Institute (CIGI, which is now Cereals Canada). As head of milling, Sarkar developed efficiencies and generated flours with desired quality attributes for food products around the globe. He retired in 2014 but continues to do consultant work with the organization.

For Sarkar, the nomination from Cereals Canada came as a surprise.

“I didn’t have the foggiest idea that I’d be getting this. No clue,” he said, adding that he’s honoured to be recognized among the greatest in Canadian agriculture.

“Some of them I know, and I have a lot of regard and respect for them,” he said. “To be there with them, sharing the same hall, that means a lot to me. I’m truly humbled by it.”

Sarkar’s childhood had a major impact on his eventual field of work.

“My father was an accountant in a flour mill back in India when I was 12 years old or so,” he said, so he and his siblings were well acquainted with the flour milling workflow.

After finishing his undergraduate degree, Sarkar took up flour milling in southern India. He later went to Switzerland to advance his education in milling and, while there, was offered an opportunity by a Montreal company that saw him emigrate to Canada.

After working in Montreal for three years, he answered the posting for a position at CIGI, where he spent the rest of his career.

“The work in Montreal was the typical work that you would expect when you’re a miller,” he said.

However, CIGI offered more than that. There was more of a connection with the international milling industry as well as secondary processing companies, like bakeries and noodle plants, he noted.

“There was also the opportunity for doing applied research with the grain scientists at the Canadian Grain Commission, since we’re in the same building,” Sarkar said.

He identifies three entities for helping him develop professionally, the first two of which are the International Association of Operative Millers and a Swiss milling company called Bühler Incorporated, known for innovation. The term “last but not least” is a massive understatement in this case, because the third entity is CIGI.

“I really owe a lot to them for giving me this exposure to connect with millers from all around the world,” he said. “There’s nothing like it. This work has been transformed into a passion because of the environment. And that became my life.”