It’s 888 CE. In Europe, the Vikings are rampaging through England and France and the Carolingian dynasty is losing its grip on the Holy Roman Empire. In China, the Tang Dynasty is in power.

In what’s now Saskatchewan, Indigenous peoples are living through a dry spell that would last another three or four decades.

Scientists from PARC — the Prairie Adaptation Research Collaborative — learned this from tree rings. That knowledge is helping inform the future.

Read Also

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

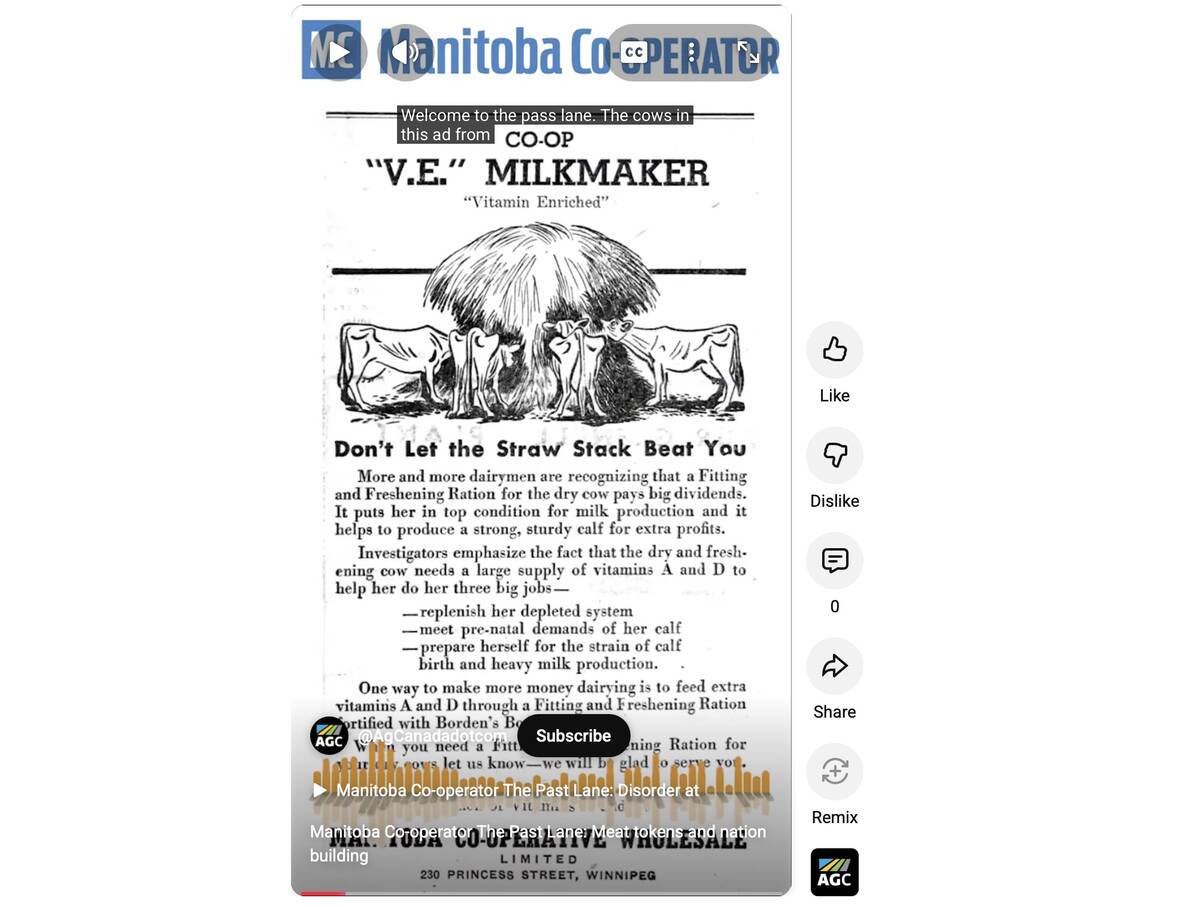

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

A lot of people know that counting the rings on a tree stump will show the age of that tree but they may not realize the rings vary in size depending on growing conditions like available moisture, light and temperature.

By analyzing the tree rings, scientists can reconstruct weather patterns going back for as many years as the sample trees have rings. It’s called dendrochronology.

Research assistant Marley Kress spoke to touring journalists in PARC’s lab at the University of Regina. She had laid out samples ranging from slabs sliced out of dead logs to thin slivers bored from live trees. Researchers don’t cut down live trees, she said. They’re not allowed.

A cabinet in the centre of the room held samples from all around Saskatchewan, Alberta, Northern Montana and North Dakota.

Two computer screens displayed scanned images of tree samples. Kress uses a computer program to analyze the rings and piece timelines together.

The theory is relatively simple. In a wet year, the tree will grow a thicker ring. In a dry year, the growth will be thinner, Kress said.

To make the difference more obvious, Kress and her fellow researchers sample trees in more water-sensitive locations — on rocky slopes, for instance. Trees in these areas should have more variation between growth rings.

On a log disc, Kress showed how the wood grew in light rings, indicating early growth, and darker, denser rings showing late growth.

The researchers take multiple samples from multiple locations, and then “cross date” them. They compare rings between samples and find where they match. Using this method, they can stretch their streamflow timeline farther back.

They can calibrate their timeline by checking the most recent years against available meteorological data, but with tree rings, they can find out what happened long before the weather stations were built.

Ancient weather, modern applications

“If you use weather data, you won’t find one of these droughts,” said David Sauchyn.

He’s the director of PARC and showed the same group of journalists the streamflow reconstruction that goes back to 888 CE.

“Look at these droughts of 20 to 30 years,” he said.

There are multiple, extended droughts on the timeline, the first stretching from 888 into the first quarter of the 900s, and the most recent lasting most of the 1800s.

No wonder that in 1857, when Captain John Palliser visited what’s now southern Saskatchewan and Alberta, he called it a “desert, or semi-desert… which can never be expected to become occupied by settlers,” as quoted in the Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

Fortunately for the Canadian government, which was determined to settle the area anyway, a wet cycle soon followed.

“[These droughts] actually happened, and they will happen in the future,” Sauchyn said. “They haven’t happened since we colonized the region.”

The millennium-long reconstruction captures extremes and long cycles that meteorological data can’t, he said.

“This record of the long-term natural variability of the regional hydroclimate informs our understanding of projections of future climate,” PARC’s website adds.

It adds to understanding of hydrology and climate that’s been derived from instrumental records, and it challenges water management and planning norms that just assume a sufficient, consistent water supply, the website adds.

PARC has used this information to help rural municipalities plan for drought, said Sauchyn.