In 1932 my grandfather moved north from the drought-stricken plains of southern Saskatchewan, to the province’s parkland region.

Chasing rain and a better life, he first homesteaded a rocky quarter, turned it back in and the next year bought an irregularly shaped piece of property, totalling 204 acres, bounded by two creeks, from the Hudson Bay Company.

That spring he and my grandmother married and she rode the train north to establish a farm in the bush with him. Decades later my brother still farms that land bought from ‘The Bay.’

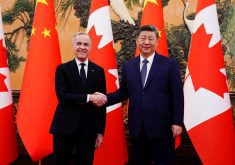

Read Also

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

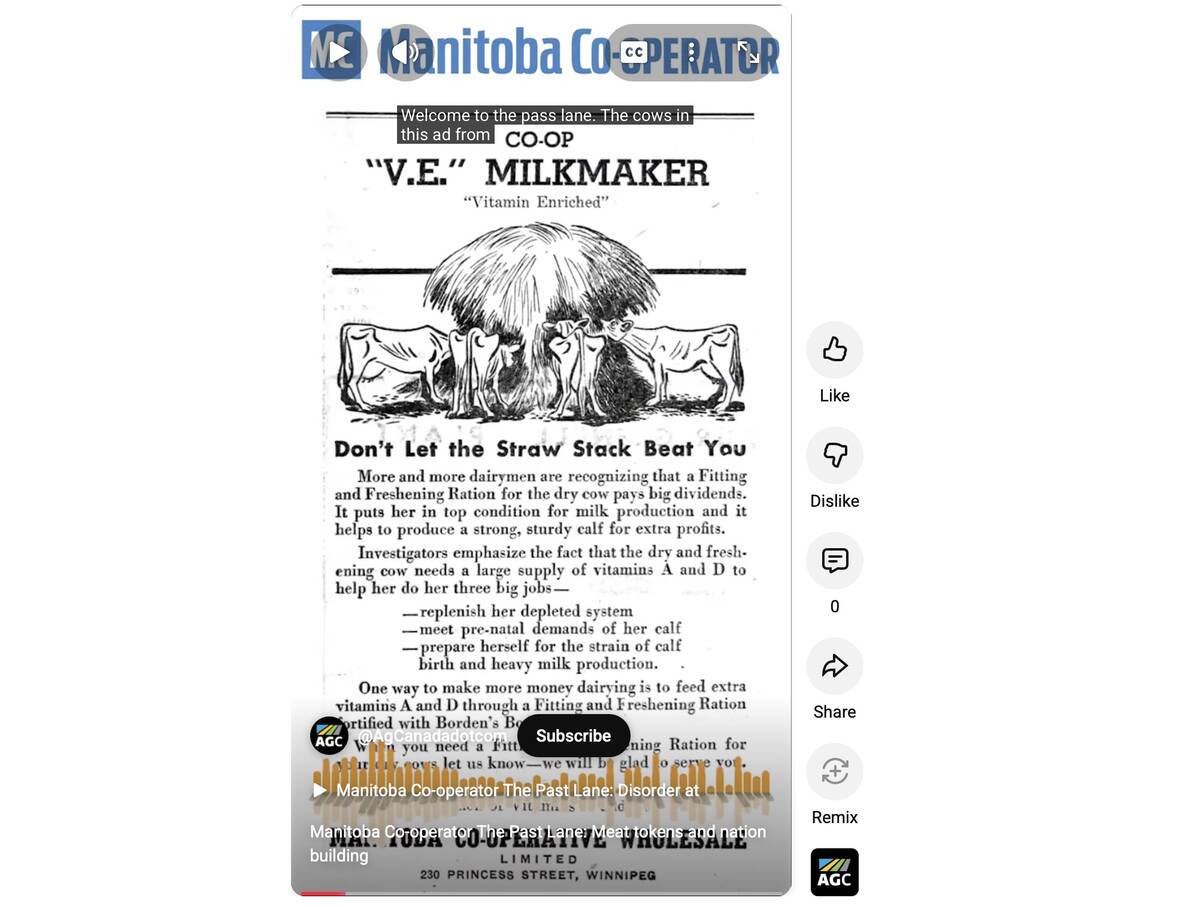

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

How HBC, one of the world’s oldest corporations and a globe-spanning behemoth in its day, came to sell farmland to modest Prairie farmers is an interesting tale.

In 1869, after rejecting an offer from the U.S. government for the equivalent of C$10 million, the company approved the return of Rupert’s Land, as most of Western Canada was then known, to Britain.

The British government then promptly loaned the new country 300,000 pounds sterling to compensate HBC for its losses. At the same time, HBC retained one-twentieth of the “fertile areas to be opened for settlement” as well as the land its fur-trading establishments sat upon.

The exchange, known as the Deed of Surrender, was at the time the largest real estate deal ever conducted, and it left the HBC owning millions of acres throughout Western Canada that it had little interest in managing from afar.

HBC’s deal with my grandfather was a more straightforward one. So much down, so much a year, for a set term, until it was paid for. A few years later, like so many western farmers of the time, he ran into tough economic times during the depths of the Great Depression.

He wrote the HBC to explain his situation. The company responded and offered to let him pay interest only, until such a time as he was prepared to resume paying on the principle of the loan. A couple of years later, the economic times had improved and he contacted the company to do exactly that, only to find they’d quietly chosen to apply his payments directly to the principal, forgoing interest.

Suffice to say the company earned a lifelong customer. And while it might seem altruistic on the part of the company, the simple truth is the HBC recognized that its competency lay not in land management, but in trading and retail networks. It didn’t want to take the land back because officials knew it wasn’t in their best interest in the long run.

Perhaps it is time for the Manitoba government to likewise consider its own role in the ownership and management of agricultural lands. After all, the provincial government doesn’t farm or ranch, so it’s a little confounding that it continues to own and lease out approximately 1.4 million acres of agricultural land, almost all of which has been in agricultural production for many decades.

We are primarily speaking of grazing lands here, and leased land has long been the backbone of many a Manitoba cattle operation.

Until recently, the province had a leasing system that appeared to have some clear-cut social targets. It granted long-term ‘life leases’ that gave the cattle producers in question certainty over their operations. It used a ‘points’ system that slanted leases towards those already in the area, and younger operators who were looking to establish or grow their operations.

That’s now been tossed out, in a move that’s proving to be very controversial. The province is establishing an ‘open-auction’ system it says will be fairer, more transparent and will better reflect the true value of the plan. Officials also cite the New West Partnership agreement between the western provinces as one of the primary drivers behind the revisions.

Among the most contentious issues has been lease length. At 15 years, the province says producers will have enough predictability and a long enough timeline to make improvements such as corrals and fencing. Affected farmers counter they’ll be left in the lurch, never sure if they’ll keep the land when the lease is up, something that will hit especially hard where there’s little private land to be had, in the northern parts of agro-Manitoba.

One has to wonder: why does the province retain ownership of this land at all? Especially the land that’s so long been leased to private individuals for agricultural use?

If the government had plans for this land, surely it has time to execute them since 1881, when the vast majority of the farming regions became part of the province during its first territorial expansion.

Selling this land to those who have been managing it would provide those farmers with a new incentive to invest and grow their farms.

If the provincial government really does believe agriculture is one of the most important pillars of the economy it needs to at least consider this possibility.