Ordinarily, when there’s a shortage of something in the marketplace, classic economic theory tells us prices will rise along with demand, until producers create more of whatever is in short supply.

It works for manufacturing, mining and even farming, where the old saying is that “nothing solves high prices like high prices,” alluding to the observable price cycles.

But what if what’s in short supply is people? That’s a far thornier problem to solve, as farmers and agricultural businesses throughout the province are discovering.

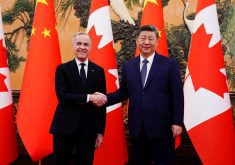

Read Also

VIDEO: Manitoba’s Past Lane – Jan. 31

Manitoba, 1946 — Post-war rations for both people and cows: The latest look back at over a century of the Manitoba Co-operator

It was the topic of a panel discussion at the recent Keystone Agricultural Producers annual general meeting where a couple of subject matter experts discussed some troubling trends.

Perhaps the most disturbing is just how fast the challenge is expected to grow here in the Keystone province, and what it will cost farmers.

A relatively small six per cent labour shortfall is already costing the sector millions a year in lost sales. By 2029, that gap is expected to grow to more than 20 per per cent.

The sector isn’t yet well positioned to fix this problem — and it’s not entirely clear large parts of it ever can be.

It might not seem like it, but agriculture has had an easy time of it until relatively recently, and the good old days aren’t likely to be coming back. Farm amalgamation created a large talent pool of people familiar with the business and available for hire.

These days there are fewer young people growing up on farms. Age and infirmity are about to catch up with another key demographic that’s long filled tractor seats throughout Western Canada — the retired farmer.

It’s as these pools have become exhausted farm labour shortage trends are only accelerating.

Now farmers are faced with finding, recruiting, training and retaining workers. And they’re resoundingly finding that it’s true: good help is awfully hard to find.

In my own personal experience I’ve seen a farm struggle with the reality that temporary foreign workers or recent immigrants might not be a great fit for a Prairie grain farm. It’s not that these folks are incapable of learning the job, but when the first time you’ve even seen a combine is the day you’re expected to run one, let’s just say there’s a bit of a learning curve.

It seems money isn’t always the answer either. One farming colleague says they offered $30 an hour recently, with no takers.

One part of the difficult math of this situation does still obey the laws of market economics. And that’s that the quality of these jobs, relative to other things on offer, is ‘lower’ in the eyes of the employees farmers need to recruit. And that’s not meant to be insulting, but rather a simple statement of fact. You may disagree with their perception, but it is their perception.

Consider it from their point of view. Anything other than the largest farms are unlikely to require year-round help. And many of them only want help during the busiest seasons. That makes a lot of economic sense for these businesses, but a whole lot less for the prospective employee. They’re mostly going to be interested in full-time permanent employment to feed, house and clothe their families.

And even the largest farms that want full-time workers have some problems. To start with, there’s the utter lack of opportunity to advance within most of these operations. Farmers want skilled, hard-working employees. But these same employees are likely to be ambitious and want to improve their lot in life. But on most farms they’ll never be the boss, own the company, or even be given a chance to manage it.

Take the emotion out of this equation and consider if you weren’t farming and were looking for work, would you take that job?

And as the skill set becomes more technically challenging, this gap is going to become even more pronounced. Instead of fighting construction companies for equipment operators, the farmer of the future is going to be battling tech companies for coders and technologists.

So far, the industry has done a relatively good job of flagging and quantifying the problem. Now what? There won’t be one single fix for this problem but there are a host of possibilities that might make a difference.

Is part of the answer allowing workers to buy shares in the farm business?

Perhaps general farm organizations such as KAP can support farmers and farm labour through group dental and health insurance or training programs for new recruits.

Maybe part of the answer lies in rural economic development initiatives designed to co-ordinate with the seasonal nature of farm work. Governments may be able to help with both training and economic development.

At their core, rural and farm folk are innovative thinkers. It’s time to put those thinking caps on.