Back when dinosaurs roamed the Earth and I was a teenager in rural Saskatchewan, my small hometown of 1,100 people had its own hospital.

Built during the booming 1970s, it replaced a 50-year-old structure the community had long outgrown. It had the usual services, including emergency medical treatment when needed.

But these days, that building is no longer a hospital. It was sold to a community organization for a dollar in the austerity-driven 1990s, and converted into an assisted living facility.

Read Also

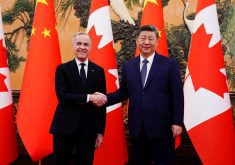

Trade uncertainty is back on the Canadian national menu

Even if CUSMA-compliant goods remain exempt from Trump’s new tariffs for now, trade risk for farmers has not disappeared, Sylvain Charlebois warns.

These days, the area farm families who need a hospital have to go another 50 kilometres farther afield to a much larger town. There is a medical clinic in my old hometown, but no primary care facility.

When seemingly everything else in rural areas has improved — better roads, expanded and improved utilities and so on — in this key area our prairie society seems to be backsliding.

At least residents of my hometown can still get ready access at nearby centres. Here in Manitoba, residents are not always so fortunate.

We’re seeing this play out here in dramatic fashion, as rural emergency rooms throughout the province are being closed this summer. I’ve heard anecdotal reports from a paramedic that one crew waited a full working day to admit a patient at the Steinbach emergency room.

[READ MORE] Medical meltdown: Know the nearest available ER, doctors urge rural residents

On Saturday of the recent long weekend, Gimli’s emergency room lacked a doctor for a good part of the day, as thousands visited the community for the return of its pandemic-halted Icelandic Festival.

At Grandview, a local medical clinic was forced to extend office hours to offer the community medical coverage when the local ER was closed for weekends.

We could go on, but it would be a long list. Doctors Manitoba says a third of all ‘rural and northern’ emergency rooms have been completely closed, and a further third have been partially closed this summer.

Stop for a minute and let that little nugget sink in. Two-thirds of the hospitals that serve rural Manitoba can no longer fulfil their pledge to their communities.

And that’s on top of the meltdown that emergency medical services in Winnipeg — often the final destination for rural patients — have undergone. This spring the median wait time, according to emergency room data acquired by media, was more than 24 hours.

That’s said to have improved somewhat, but it’s still a symptom of a very sick provincial medical system.

A big part of the problem seems to be staffing levels. Like other areas of the economy, hospitals are struggling to find enough qualified staff.

There are some pretty predictable reasons for this. The pandemic burned out a lot of doctors and nurses. And the demographics aren’t working in favour of the province, as more doctors and nurses opt to retire.

The fact that the province is so woefully unprepared for this speaks to a failure of provincial leadership. For decades now, demographers have warned that as the ‘boomer’ generation retired, they’d leave a massive workforce vacuum behind them. Yet, despite decades of warning, the province is now scrambling to qualify enough doctors and nurses to maintain services. This will take years to accomplish.

That’s a very worrisome situation for rural Manitoba residents, especially for farmers, their families and their employees. Farming is a high-risk business and routinely is listed among the most dangerous professions in Canada.

And especially dangerous is the upcoming harvest season. During this time of year, the predictable combination of stress, exhaustion and too much work in a too-short season brings a spike in farm accidents.

Add the reality that medical attention could now be some distance away, and it’s an unacceptably high risk for the province’s farm families.

At the farm level, this means you and your employees will have to be especially careful this fall. There’s never a good time to skimp on safety, but this is certainly going to be a season when it’s in your best interests to double down.

That means taking extra time now to ensure all equipment is in safe operating condition. Have a plan to fall back on in case anything does go wrong. Have some basic first-aid supplies on hand and an inkling of what to do with them.

Take time to make sure you’ve got a workable system to get first responders to your various farm locations. They say time is money, but in this case, it could very well be the difference between life and death.

Longer term, however, Manitoba’s health care system needs fixing and it’s not entirely clear the provincial government sees that.

Make a point to remind local representatives that you’re a taxpayer too, and have a right not to be treated like a second-class citizen just because you don’t live within the Perimeter Highway.